Watching deep-space fireworks

An orbiting telescope records the universe’s most powerful explosions

Share this:

- Share via email (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share to Google Classroom (Opens in new window) Google Classroom

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

|

|

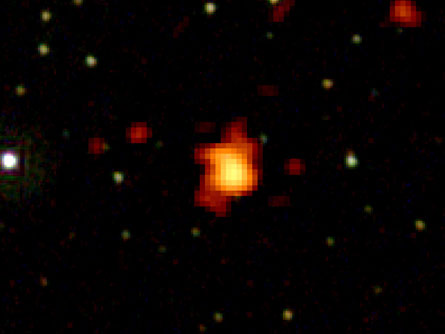

The X-ray afterglow of the record-breaking gamma-ray burst recorded on September 15, 2008 appears orange and yellow in this composite image taken by NASA’s Swift satellite.

|

| Stefan Immer, Swift/NASA |

Space is full of fireworks: Galaxies smash into each other, dying stars explode and high-energy particles race toward us at the speed of light. The most powerful explosions in the universe are brilliant flashes of light called gamma-ray bursts. If you happened to fly through the neighborhood of a gamma-ray burst, you couldn’t miss the flare — it would be brighter than a million trillion suns.

On September 15, 2008, a gamma-ray burst in the constellation Carina (which is best seen from the Southern Hemisphere) was recorded. This February, after studying the data, astronomers announced the gamma-ray burst was the most energetic explosion ever seen.

What, you didn’t see it? That’s not surprising, since the explosion was more than 12 billion light-years away.

Gamma-ray bursts are nearly impossible to study from Earth because our atmosphere blocks the view. But scientists found a way around that problem. Last June, NASA launched a new telescope called the Fermi Gamma-ray telescope into orbit by strapping it on the back of a rocket. The instrument is helping scientists watch these deep-space fireworks displays. It’s named after Enrico Fermi, an Italian-American physicist who helped design the first atomic bomb and also studied gamma-ray bursts.

Since they were first observed more than 35 years ago by satellites, these bursts of energy have been one of the biggest mysteries of space. Where do they come from? Why do some bursts last only a fraction of a second while others last a few minutes?

The outburst that occurred in September was extraordinary. It lasted for more than 23 minutes — 700 times longer than the typical gamma-ray burst. Although scientists aren’t sure what caused it, they do have some theories.

If a star is big enough, it collapses into a black hole when it runs out of fuel. A black hole is a dense and dark object with gravity so strong that not even light can escape from it. Many astronomers believe that as the star fades away and becomes a black hole, it shoots gamma rays into space. In other words, if you had seen the gamma-ray burst last September, you might also have been watching the birth of a powerful black hole. Less powerful gamma-ray bursts may come from other kinds of stars as they run out of fuel — or collide.

The first observations from the Fermi telescope are helping scientists answer questions about gamma-ray bursts. But as the data comes in, and astronomers learn more about these deep-space fireworks, other questions will arise. That’s the nature of good science — the answer to a question leads to another question, and its answer leads to yet another question that needs to be answered.