Analyze This: Salt may quash lightning over the sea

Bits of airborne salt may rob clouds of water needed for lightning bolts to crash

To make lightning, water droplets in clouds need to travel up high and freeze. But salt particles in the air can help big droplets form, making rain instead of lightning.

Image by Chris Winsor/Moment/Getty Images

Share this:

- Share via email (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share to Google Classroom (Opens in new window) Google Classroom

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

Lightning may be lacking over the ocean. And sea salt — a seasoning that’s no stranger at the dinner table — may explain why.

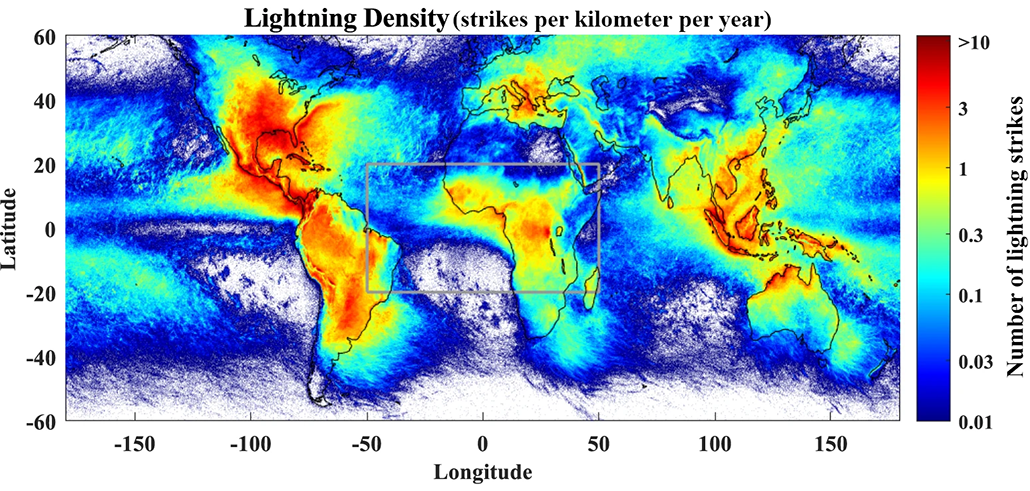

“Most of the lightning occurs over land — the vast majority, more than 90 percent,” says Daniel Rosenfeld. A cloud physicist, Rosenfeld works at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in Israel. He and his team wondered why lightning was scarcer at sea even though more precipitation falls over the ocean.

One factor that could affect lightning is aerosols. Aerosols are small particles that waft in the air. They provide landing pads for water to condense and form droplets. When droplets rise high into a cloud — where it’s colder — the water can freeze into a collection of particles and pellets. These ice pieces rub together to create electrical charges that can form lightning.

Over land, aerosols tend to be relatively small. They’re usually smaller than 1 micrometer. That’s about one hundred times smaller than a strand of hair. But at sea, salt spray can fill the air with larger aerosols — pieces of salt bigger than 1 micrometer.

To study the role of aerosols in lightning, Rosenfeld’s team zoomed in on an area that included central Africa and much of the Atlantic Ocean. They used satellite imagery to watch how clouds developed there between 2013 and 2017. They also compiled data on aerosols in that area and estimated those from sea salt.

Aerosol effects

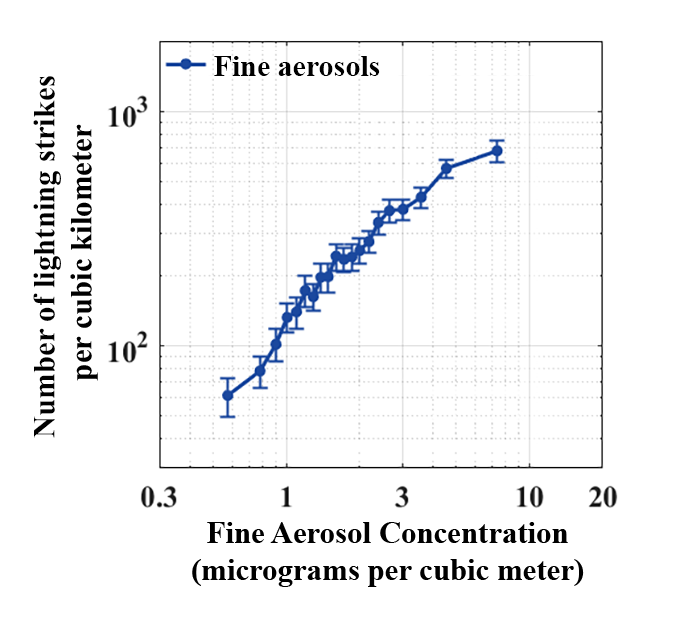

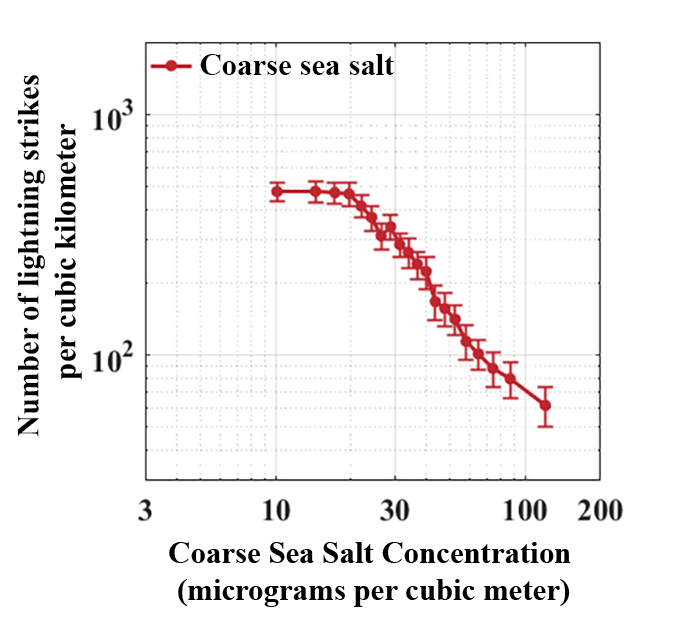

Over one region of the Earth, the team watched how cloud systems formed and what factors may contribute to lightning. They investigated how the amount of lightning changed with various amounts of differently sized aerosols in the air. Fine aerosols are smaller than 1 micrometer (left). Coarse sea salt is larger than 1 micrometer (right). These graphs show the lightning density, or the number of strikes per cubic kilometer. Those numbers are adjusted to account for the amount of precipitation in the cloud systems, which is an important factor in forming lighting bolts.

Both over the ocean and over land, an increase in small aerosols was linked to more lightning. That could be because such tiny aerosols form small water droplets that can rise high in the air, freeze and help make lightning. But an increase in the large aerosols often found over the ocean was linked to less lightning. This may be because hefty sea salt particles cause relatively large drops of water to form. These fall out of the cloud before they can freeze and electrify the cloud.

The team shared its findings August 2 in Nature Communications.

Understanding how aerosols impact clouds could help make weather predictions and climate models more accurate, Rosenfeld says. Aerosols are important to rainfall. “You can’t get it right without getting the aerosols right.”

Where lightning strikes

Researchers collected data on where and when lightning strikes occurred around the globe between 2013 and 2017. This heat map shows how lightning density varies across the world. The box in the center shows the area where scientists tracked cloud systems.

Data Dive:

- Look at the world map. Which areas have the highest density of lightning?

- How does lightning density over land compare with that over the ocean?

- Can you think of another way to present these data? How might you show these data if you wanted to include when strikes occurred?

- Look at the pair of graphs. What is the range — or the spread — of values for fine aerosol concentration? How does the density of lightning change with increasing fine aerosol concentration?

- What is the range of values for coarse sea salt concentration? How does the density of lightning change with increasing aerosol concentration?

- Compare the trends on the two graphs. Which type of aerosol seems to help lightning form? Which type may hinder lightning?

- Can you think of other particles in the air that may impact clouds and lightning?