Mice can teach us about human disease

Scientists understand what fewer than one-fifth of human genes do; probing mice can help fill the gaps

While humans and mice look and act very differently, 85 to 90 percent of our genes are the same or similar. So if scientists can understand the instructions in every mouse gene, people will get a good idea of the instructions in virtually every human gene as well.

Global Panorama/Flickr (CC-BY-SA 2.0)

Share this:

- Share via email (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share to Google Classroom (Opens in new window) Google Classroom

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

Zorana Berberovic gently lifts a small black mouse by its tail. As its hind legs rise up off the floor of its cage, the research technician slips a tiny vial under the mouse’s bottom. Berberovic lightly strokes her gloved finger against its belly. Within seconds, she is rewarded. A dribble of pee enters the vial.

“They have small bladders so there’s not much,” Berberovic says. Luckily, she adds, “We don’t need much.”

It’s hard to imagine that someone might need any mouse pee at all. But there could be a lot to learn from the urine of this particular mouse. It could help scientists better understand important aspects of human disease.

Berberovic works at the Toronto Centre for Phenogenomics (FEE-no-geh-NO-miks) in Toronto, Canada.

Wait: pheno-what?

Pheno is a prefix that comes from the Greek word meaning “to show.” Biologists often borrow this prefix to explain the basic traits of an organism: its phenotype. A mouse tends to be small, furry, four-footed and shy with a long, naked tail. Those descriptions are all part of its phenotype. Meanwhile, genomics is the study of the genetic material an organism has inherited from its parents. When combined, these two terms describe the study of how an organism’s genome contributes to its phenotype — or those traits we can observe.

The Toronto center is one of 18 institutes around the world that make up the International Mouse Phenotyping Consortium. Scientists at these institutes are working together to figure out the function of every mouse gene.

A gene is a segment of DNA that influences how an organism looks and functions. While humans and mice look and act very differently, 85 to 90 percent of our genes are the same or at least very similar. So by understanding the instructions in every mouse gene, people should get a pretty good idea of the instructions in virtually every human gene too.

Berberovic and her fellow researchers even want to know which genes affect pee. They especially want to know whether chemicals that the body dumps into urine can tell us how healthy — or sick — an individual might be.

But the consortium’s many scientists are looking well beyond pee. Their research may tease out which genes affect an animal’s size, weight, behavior — even lifespan. Matching a gene with the effect it has on those characteristics or traits is called phenotyping.

Ann Flenniken is a molecular geneticist at the Toronto center. (It’s run jointly by Mount Sinai Hospital and The Hospital for Sick Children, both in Toronto.) She studies what genes do and the chemical basis for those functions.

By working together, she says, the global phenotyping consortium hopes one day to amass “a catalogue of all gene functions.”

So many genes, so little information

The cells in all living things contain genes. They’re made from DNA. And those genes instruct cells about what to do as they develop, grow, interact with their neighbors — and ultimately die. Some instructions might guide an organism’s vision or its hearing, Flenniken points out. They might determine its reproductive habits or even the way the animal walks. You might think of a gene as a blueprint for a certain cellular task.

Proteins are what carry out those tasks. So a gene’s DNA really provides instructions for making proteins, Flenniken explains. Proteins are an essential part of all living organisms. They form the basis of living cells and tissues (like brain, muscle and skin). But just as importantly, proteins do the work inside of cells.

Both humans and mice have roughly 20,000 genes. Right now, scientists understand the function of fewer than one out of every five of those genes.

That’s frustrating for someone like Jim Woodgett. He is a cell biologist and the director of research at Toronto’s Mount Sinai Hospital.

“We don’t know about 80 percent of the instructions for life. That’s unbelievable,” Woodgett says. “It’s essential that we learn what genes do.”

Mechanics can’t fix cars if they don’t know how each part works, he notes. Similarly, doctors can’t treat human diseases if they don’t know how the genes that play a role in those ailments work.

Looking for defects as a clue to treatments

Woodgett studies causes and treatments for a wide range of illnesses. These include cancer, diabetes, Alzheimer’s disease and bipolar disorder. (That last one is a mental illness characterized by alternating periods of extreme depression and extreme joy.)

Perhaps a gene normally produces a protein that stops cancer cells from growing. Someone who inherits a faulty copy of that gene might face a higher than normal risk of getting cancer.

But if scientists could identify that gene, they might be able to create a medicine that overcomes the defect. An example might be a drug that contains the very protein that the faulty gene was supposed to make.

Yet until scientists such as Woodgett learn how most genes work, such treatments will remain only a dream.

Ka-pow! Knocking out genes

Researchers with the International Mouse Phenotyping Consortium are looking for answers. In fact, they have already made an important discovery at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, in Cambridge, England.

The institute’s researchers discovered what each gene did by first turning it off and then observing what happened. In fact, all researchers in the phenotyping consortium use mice with inactivated genes.

“We turn off one gene at a time,” explains geneticist Jacqueline White. She is the lead manager for mouse phenotyping at the institute. All remaining genes in the animals continue to work normally. Consortium scientists “then all run the same tests on the mice,” she explains. These may include tests on their hearing, vision, urine and blood — even how easily the mice become startled.

When scientists turn off a gene’s instructions, they “knock out” its function. So scientists refer to a mouse with an inactivated gene as a “knock-out mouse.”

Here’s how they create such an animal:

Genes are made of two intertwined strands of DNA. Ladder-like rungs link each strand to its partner. Each rung on the ladder is made from two chemicals known as nucleotides.

Instructions for making proteins are determined by the order of those nucleotide pairs in a gene. Changing their order changes the instructions they will later give to cells. Scientists can deliberately change the order of nucleotides in a gene so that its recipe no longer makes its intended protein. Doing this turns off — or knocks out — the gene.

Sometimes the switched-off gene is so important that a developing mouse won’t survive to birth. Indeed, “about 20 to 30 percent of the genes we knock out end up causing mice not to survive,” says Kent Lloyd. He’s a veterinary scientist at the University of California, Davis. That university is part of the International Mouse Phenotyping Consortium.

When this prenatal death occurs, “Often it’s because the gene we knocked out affects the heart,” Lloyd says. “If the heart doesn’t work, the animal dies.”

Engineering the right stuff in your mouse

Many human embryos don’t survive. Scientists would like to know whether genes might underlie the problem (as opposed to trauma or infection, for instance). That’s another question the consortium researchers hope to tease out with the help of their mice.

In the wild, a gene can vary quite a bit from mouse to mouse. But in a strain of mice, all of the genes are very similar. This consistency is important.

The researchers want to make sure that small differences in gene types don’t affect test results. They want to know the only thing affecting the way the animal’s body looks or functions is the presence (or absence) of a particular working gene.

Inbreeding to quickly and efficiently isolate desired genetic traits would be much harder in humans. We have longer lives and take much longer to reproduce than mice do. More importantly, breeding people for research would violate many beliefs, values and laws.

That is why these furry mammals are the subjects of so many experiments — experiments ultimately meant to tease out the mysteries of human genes.

All scientists in the global phenotyping consortium use a strain of mouse called C57BL/6. Although black, these mice otherwise resemble normal field mice. What is really different about them isn’t visible to the eye: The genes in every member of this strain are almost totally identical.

A special committee of scientists and non-scientists also oversees every experiment to make sure that the scientists treat their mice as humanely as possible.

For example, mice are kept in groups of up to five in a cage. That is because they prefer the company of other mice. Researchers feed the animals regularly and give them exercise wheels or toys to stimulate their minds. They provide the mice comfortable bedding material to make nests, and replace that bedding when urine and feces soil it. Scientists also ensure the mice are protected from predators and infections.

Observes Flenniken, “These animals suffer far less in our facility than they would in the outside world.”

Still, she and other scientists understand why people may be uncomfortable with performing experiments on animals. “There are ethical and moral issues to using animals in research, especially when we are the beneficiaries,” says Woodgett. However, he adds: “The alternative is to say ‘Let’s test this not on a mouse, but on you.'”

Power words

(For more about Power Words, click here)

Alzheimer’s disease An incurable brain disease that can cause confusion, mood changes and problems with memory, language, behavior and problem solving. No cause or cure is known.

beneficiaries The individuals who receive money, better health or some other type of benefit from some activity, decision or process.

bipolar disorder Also known as manic-depressive illness, this mental illness causes individuals to experience periodic swings in mood, energy and activity levels. In one phase, someone may feel intense joy and actively engage in lots of activities and interactions with other people. Later (sometimes only a day or two later), the individual can enter a period of intense depression. Now the patient is sad, may have no interest in seeing or talking to others and may want to just lay low, indoors and alone. This disease tends to run in families, suggesting there may be a genetic vulnerability. Fortunately, there are a number of treatments for this disease.

bladder A flexible bag-like structure for holding liquids. (in biology) The organ that collects urine until it will be excreted.

cancer Any of more than 100 different diseases, each characterized by the rapid, uncontrolled growth of abnormal cells. The development and growth of cancers, also known as malignancies, can lead to tumors, pain and death.

consortium A group or association of independent organizations.

depression A mental illness characterized by persistent sadness and apathy. Although these feelings can be triggered by events, such as the death of a loved one or the move to a new city, that isn’t typically considered an “illness” — unless the symptoms are prolonged and harm an individual’s ability to perform normal daily tasks (such as working, sleeping or interacting with others). People suffering from depression often feel they lack the energy needed to get anything done. They may have difficulty concentrating on things or showing an interest in normal events. Many times, these feelings seem to be triggered by nothing; they can appear out of nowhere.

diabetes A disease where the body either makes too little of the hormone insulin (known as type 1 disease) or ignores the presence of too much insulin when it is present (known as type 2 diabetes).

DNA (short for deoxyribonucleic acid) A long, spiral-shaped molecule inside most living cells that carries genetic instructions. In all living things, from plants and animals to microbes, these instructions tell cells which molecules to make.

embryo The early stages of a developing vertebrate, or animal with a backbone, consisting only one or a or a few cells. As an adjective, the term would be embryonic.

ethics A code of conduct for how people interact with others and their environment. To be ethical, people should treat others fairly, avoid cheating or dishonesty in any form and avoid taking or using more than their fair share of resources (which means, to avoid greed). Ethical behavior also would not put others at risk without alerting people to the dangers beforehand and having them choose to accept the potential risks.

gene A segment of DNA that codes, or holds instructions, for producing a protein. Offspring inherit genes from their parents. Genes influence how an organism looks and behaves.

genome The complete set of genes or genetic material in a cell or an organism. The study of this genetic inheritance housed within cells is known as genomics.

humane An adjective that refers to the caring and compassionate treatment of animals.

inbreeding The mating of animals that are too closely related, genetically. It is the opposite of genetic diversity. Animals that are inbred tend to become weak or sickly and often cannot reproduce successfully.

knock out (in genetics) An organism that has been bred or engineered to disable, or turn off, one particular — and important — gene. The term gets its name because the function of this gene has been knocked out by the procedure.Scientists can now identify the function of the missing gene by seeing what changes when it no longer works.

molecular genetics The branch of biology that focuses on the structure and function of genes.

nucleotides The four chemicals that link up the two strands that make up DNA. They are: A (adenine), T (thymine), C (cytosine) and G (guanine). A links with T, and C links with G, to form DNA.

phenotype (in biology) A term derived from the Greeks terms for “to show” and “type.” It refers to all characteristic features of an organism that can be observed. This would include its size, shape, color — even how it would typically behave. These traits stem both from its genes (what it inherited from its parents) and its “environment” — including its diet. Although individuals of a species — or even a subgroup, such as a strain —may vary somewhat, the common traits of the entire group will be its phenotype.

predator (adjective: predatory) A creature that preys on other animals for most or all of its food.

prenatal An adjective referring to something that occurs before birth.

proteins Compounds made from one or more long chains of amino acids. Proteins are an essential part of all living organisms. They form the basis of living cells, muscle and tissues; they also do the work inside of cells. Among well known stand-alone proteins: the hemoglobin in blood and the antibodies that attempt to fight infections. Medicines frequently work by latching onto proteins.

species A group of similar organisms capable of producing offspring that can survive and reproduce.

startle The response some animal has when surprised or suddenly alarmed.

strain (in biology) Organisms that belong to the same species that share some small but definable characteristics. For example, biologists breed certain strains of mice that may have a particular susceptibility to disease. Certain bacteria may develop one or more mutations that turn them into a strain that is immune to the ordinarily lethal effect of one or more drugs. (in medicine) Stretching or tearing of muscle or tendons, which are the fibrous bands that connect muscle to bone.

trauma (adj. traumatic) Serious injury or damage to an individual’s body or mind.

veterinary Having to do with animal medicine or health care.

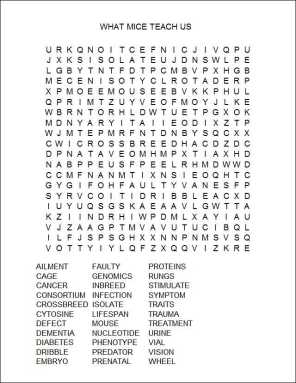

Word Find (click here to enlarge for printing)