Rare blue diamonds form deep, deep, deep inside Earth

Their recipe includes boron that may have ridden to great depths aboard a sinking tectonic plate

Share this:

- Share via email (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share to Google Classroom (Opens in new window) Google Classroom

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

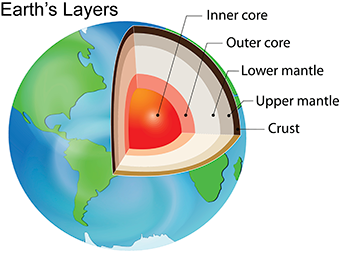

Blue diamonds are among the rarest of gems. Earth’s mantle is that deep, hot layer between Earth’s crust and core. And it’s here that these diamonds are born. Yet their blue hue comes from boron, an element not commonly found there. Scientists now think they’ve figured out how the boron got there. Their analyses suggest that sinking pieces of Earth’s crust ferried the boron deep down from the crust. If true, the blue gems’ birthplace is among the deepest of any diamonds.

Evan Smith and his colleagues made the new findings. Smith is a geologist at the Gemological Institute of America, based in New York City. That institute has studied millions of diamonds from around the world. Only a small share of them — about two in every 10,000 — are blue. And only a few blue diamonds have tiny bits of non-diamond material, called mineral inclusions, inside their crystal structure.

Those inclusions trap minerals that were in the vicinity when the diamonds formed. They therefore can offer clues to the gem’s origins. Whenever the researchers came across a blue diamond, they checked for those inclusions. Altogether, Smith and his colleagues found and analyzed 46 blue diamonds with these inclusions.

Their structure and chemical recipe point to an origin more than 660 kilometers (410 miles) deep. That’s below the boundary between the mantle’s upper and lower layers. All diamonds form within Earth’s mantle, but most form above that boundary layer.

Smith’s team described its findings August 1 in Nature.

Telltale chemical hitchhikers

Gem experts refer to inclusions as a type of flaw. Blue diamonds are not just extremely rare, but also very pure, Smith reports. “They’re quite often completely flawless.” That made it difficult for researchers to identify enough blue diamonds with mineral inclusions to study.

The team probed the inclusions using something known as Raman spectroscopy. This didn’t require cutting into the stones to gain clues on how deep their birthplace had been. They merely shone a laser beam onto the inclusions in each of the 46 stones. Then they measured the wavelengths of light scattered by these inclusions. Diamonds are made of carbon. Like chemical fingerprints, those wavelengths told scientists what other elements the inclusions held.

Certain minerals, such as bridgmanite (BRIDJ-maan-eit), are stable only at the high temperatures and pressures found deep inside Earth. Such minerals change in structure as the diamonds holding them rise through the Earth in molten rock. But the inclusions also keep traces of the deep, high-pressure forms. The researchers used these molecules to better understand the blue diamonds’ origins.

“It’s a bit of detective work to trace back what you see in the diamond,” Smith says. For example, a diamond might hold both bridgmanite and ferropericlase (Fair-oh-PAIR-ih-klaes). Both minerals come from the lower mantle. (Indeed, bridgmanite becomes common at about 660 kilometers down.) Seeing the two minerals together means the diamond formed very deep. That combo would not have been stable at shallower depths, Smith says. “It’s like oil and water. Under certain conditions they mix, but under others, they don’t.”

And now, about that boron . . .

The element boron usually prefers to stay in Earth’s crust. So scientists were puzzled how it could have gotten deep enough to end up inside a blue diamond. The likeliest explanation, Smith’s team says, is that the boron hitched a ride on a tectonic plate.

These large slabs of rock, which make up the planet’s surface, are always on the move. Some slowly push toward one another. Others are pulling away from each other. Still others grind sideways past each other. When two plates collide, the plates may scrunch up to form mountains. Or one plate may slide under another. The process where a collision sends one plate deep into Earth’s is called subduction.

Much plate pulling and pushing takes place beneath the oceans. Seawater contains dissolved boron. As this water moves along the seafloor, it reacts with certain minerals to form a water-rich mineral called serpentinite (Sur-PEN-tih-neit). If this mineral is in a tectonic plate that subducts during a collision, that sinking plate will carry the mineral deep into the mantle. That’s one way to enrich the mantle with boron.

The hypothesis also points to one way that water may travel deep into the mantle: hitchhiking within serpentinite.

Scientists had long wondered just how far down water can go. They have suspected that water might help keep tectonic plates moving by lubricating surfaces deep within the planet. Finding serpentinite, Smith says, is “not proof, but a glimmer of hope that we’ve got actual water being transported from the ocean down to the lower mantle.”

Using diamonds to study how boron moves through Earth is clever, says Graham Pearson. He’s a geochemist at the University of Alberta in Canada and wasn’t connected with the study. “Virtually nothing is known about the boron cycle in the deeper parts of the mantle,” Pearson adds.

He and other researchers are now studying boron isotopes — forms of the element with different masses — inside blue diamonds. This might help them pin down whether the boron in the crystals came from the crust or from the mantle.

Because blue diamonds in the new study all contained inclusions, they’re not perfect. They would be less expensive than flawless blue diamonds, such as the world famous Hope Diamond. Still, the research value of flawed blue diamonds, as seen in this new study, may boost their value, Smith says. “I think it makes them a little more special.”