Family, friends and community inspired these high school scientists

Finalists in this year’s Regeneron Science Talent Search tackled problems close to home

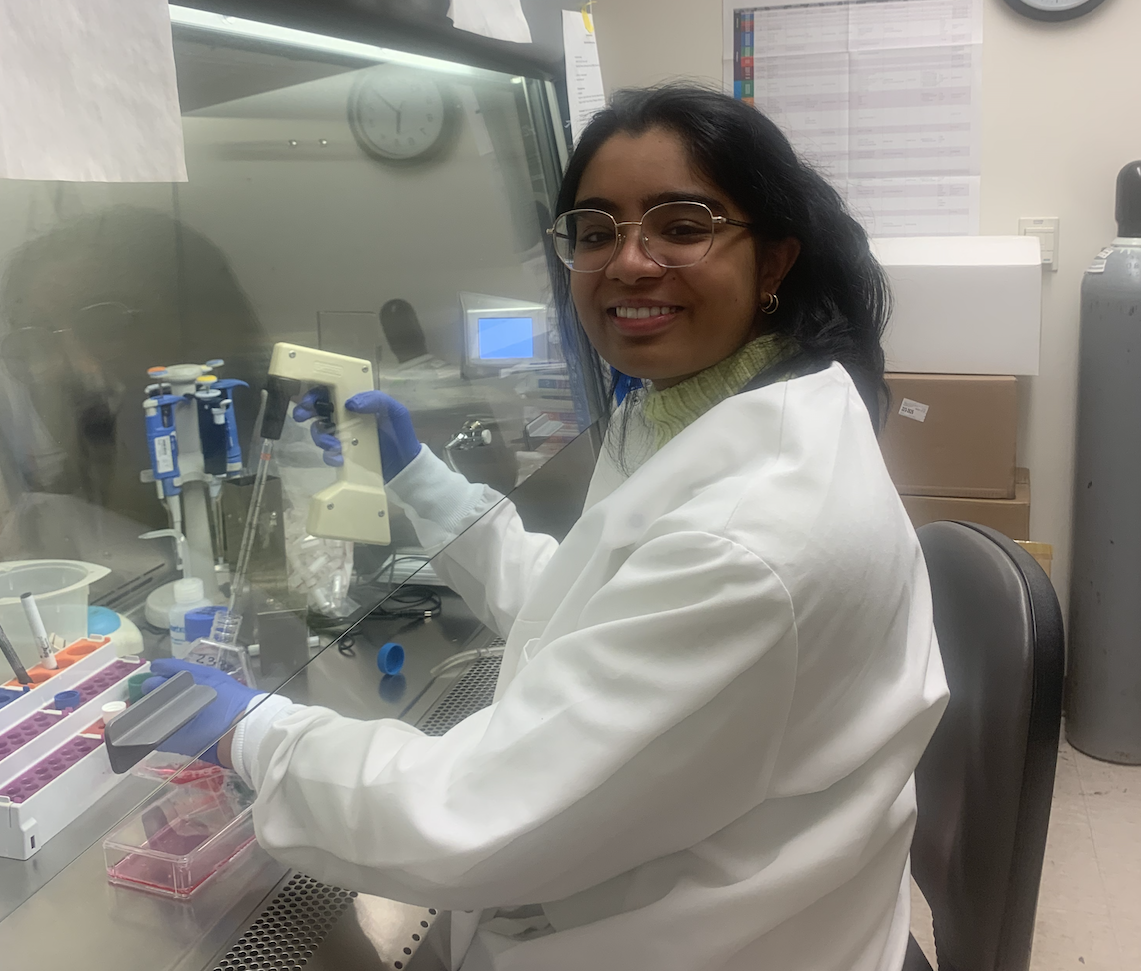

Aditi Avinash (pictured) was inspired to study gluten intolerance by family and friends with this condition. “Starting a research project and being like, ‘I want to be a researcher,’ was daunting,” she says. “But kind of just being like, ‘Oh, how can I help my friends and support their life choices?’ is much more attainable.”

Aditi Avinash

Share this:

- Share via email (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share to Google Classroom (Opens in new window) Google Classroom

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

The people around us can be great help when completing a science fair project. Family and teachers can offer support and mentorship. Friends can be sounding boards for ideas. And community members can even offer inspiration for questions to answer and problems to solve. That’s where a few finalists in this year’s Regeneron Science Talent Search, or STS, got their ideas.

STS is a science and math competition for high school seniors. It’s run by Society for Science, which publishes Science News Explores. Each spring, 40 STS finalists gather in Washington, D.C., to share their research and compete for more than $1.8 million in awards. Science News Explores spoke to three of this year’s finalists about where they got their ideas, what resources helped them and what they got out of their projects.

Charisse Zou

Charisse, 17, was curious how two common pest-killing chemicals might affect honeybees. So she built mazes in her backyard and trained bees to fly through them. This helped her test the bees’ memories. One insecticide harmed the medium-term memory of her bees. Another had more severe effects, damaging the insects’ long-term memories. Charisse hopes her research will discourage people from using these chemicals where they could hurt honeybees — which are important pollinators. Charisse attends Dougherty Valley High School in San Ramon, Calif.

What inspired this project?

“It was kind of a chance encounter. I was at my local flea market, and there was a vendor there who was selling his natural, homegrown honey,” Charisse says. She asked him some questions about beekeeping, and he invited her to one of his workshops. “As I got more involved in my local beekeepers’ community,” Charisse says, “I actually learned more about how pesticides or insecticides were affecting [honeybees] … which kind of spurred my project.”

What’s been your favorite part of this project?

“Working with the bees. I was out there basically every afternoon,” Charisse says. “At first, I was kind of apprehensive about working with bees.” But Charisse came to love caring for her two beehives. “I still have my honeybees in my backyard, and we still produce honey,” Charisse says. “Out of my research, beekeeping has definitely become a lifelong hobby.”

What resources helped you?

“I read a lot of researchers’ past research papers,” Charisse says. “As an independent researcher who didn’t have much help from a mentor who was working in a lab, I think just reading those research papers really helped me. … I went into this basically a complete newbie. So I think that gave me a lot of perspective on how things should be conducted and basically the overall scientific process.”

Any advice for other research newbies?

“My advice would be to truly believe that science and innovation can really spur from humble roots. I think when a lot of people think of science, they think it’s very professional. Like all professional labs and professors. But I would say that you don’t need a Ph.D. to do amazing research.” Charisse did everything from home, building bee mazes from toilet paper roles and other recycled materials. “It was definitely not anything extremely fancy,” she says. But following the scientific method with her homemade lab setup still yielded useful, interesting results.

Amanrai Singh Kahlon

Amanrai (Rai), 17, aims to improve a walking aid for people who have cerebral palsy. To work, this tech needs a precise map of someone’s walking style, or gait. But mapping someone’s gait often requires special lab equipment. Here, Rai collected gait data with low-cost motion sensors, which he placed on the legs of 30 kids and teens. He hopes such data could someday speed up the creation of customized walking devices. Rai attends Sanford School in Hockessin, Del.

What inspired this project?

“I have a long-term family friend that has cerebral palsy,” Rai says. So as a freshman, he started volunteering at a gait lab at his local university. “I spent a lot of time in the lab collecting data, processing data,” he says, which inspired his own project. “The motivation was kind of to help that broader cerebral-palsy community.”

Why did you decide to work with kids and teens?

Right now, most prosthetics for adolescents are either of two types. Some are “the static variety … they don’t move,” Rai says. “Then there’s active prosthetics that are motorized and will help patients with cerebral palsy [walk].” But active prosthetics can’t easily be reprogrammed as kids grow and their gait changes, Rai adds. So it’s important to identify motion sensor data that active prosthetics can use to learn from a child’s changing gait. Then, these devices could adapt their motion in response to that.

What was the biggest challenge?

Rai wanted to collect motion sensor data not only on an indoor treadmill but also outdoors. But the sensors stopped producing good data when they got too far from the laptop that was recording their signals. “To combat that, I’ve actually mounted my laptop with a car battery … on my bicycle,” Rai explains. Then, he walked his bicycle alongside every research participant as they walked outside.

“In traditional research, that might be seen as rudimentary,” Rai says. “To me that was like, ‘OK, this is a teenager doing research on other teenagers. And this is how we solve this problem.’”

Any advice for completing a long-term project?

Routine is key, Rai says.

During the months he collected data, “I did it at my house. So it was easy to knock a few people out every day, on my treadmill in the basement and then walking outside in my neighborhood.”

Rai also worked with a professor and other lab members at a local university. The team met every week. “That kind of kept me accountable for getting the work done,” Rai says. It also helped to be surrounded by a group of people all working toward the same goal.

Aditi Avinash

Aditi, 17, dreams of creating a pill that lets people with celiac disease — or gluten intolerance — eat wheat. People with this condition have a hard time digesting proteins in wheat that are known as gluten.

For her project, Aditi tested three enzymes from fruits that had been shown to break down gluten. Combining the chemicals made them even better at breaking down the proteins, she found. Aditi attends Rock Canyon High School in Highlands Ranch, Colo.

What inspired this project?

Aditi recalls a freshman biology class in which her teacher talked about enzymes “and specifically about the Lactaid pill.” That pill contains an enzyme to aid digestion in people with an intolerance to the lactose in dairy products.

“That kind of got me curious as to why there wasn’t a Glutaid pill, especially because I have a lot of friends who have celiac or are gluten intolerant. And a lot of people in my family are gluten intolerant,” she adds.

What resources helped you?

“My research started off so incredibly simple. It was like, me reading different articles in my room and highlighting,” Aditi says. Later, she got help from her science teacher and found a research mentor at a local university.

“You have to remember that you are a high school student doing research,” Aditi says. “So it’s not a humbling or embarrassing thing to ask for help.”

Any advice for finding a mentor?

Just sending emails introducing yourself and your ideas “go a long way,” Aditi says. “You don’t get very many responses back. But the people who do respond back to you are so nice and so helpful.”

Aditi also suggests picking a topic you’re passionate about rather than something you think will sound impressive. “You don’t have to be solving cancer to learn something and have a valuable project,” she says. When you’re actually excited about what you’re doing, “your passion shines through to whoever you’re talking to, and someone is going to notice that, and hopefully … offer to help.”

What’s been your favorite part of this project?

“A big thing is just my capacity to problem-solve,” Aditi says. She describes herself as “an anxious planner” who likes to know exactly what’s going to happen and when. But “every day of research is just so different,” she says. “You can have a plan and a set schedule, but nothing really goes according to plan.”

It’s been really cool to see, Aditi says, that when this happens she is able to think on her feet and adapt to new challenges.

And the winners are…

At a March 12 ceremony, Achyuta Rajaram won the $250,000 first-place prize for this year’s Regeneron Science Talent Search. The 17-year-old from Exeter, N.H., devised a way to find out which parts of a computer model are involved in making decisions. This work could help make algorithms more effective, fair and safe.

The second-place prize of $175,000 went to Thomas Cong, 17, of Ossining, N.Y. He investigated the rapid growth of certain types of cancers. And the third-place prize of $150,000 went to Michelle Wei, 17, of San Jose, Calif. She found a way to more quickly solve certain types of math problems that are often used in various industries, from scheduling airline travel to distributing electricity on the power grid.

Aditi Avinash was chosen by her fellow finalists for this year’s Seaborg Award. That award goes to the finalist who most exemplifies their class and the qualities of Glenn T. Seaborg — a Nobel Prize–winning chemist devoted to promoting public understanding of science.