Roller coaster thrills

Riding roller coasters is about the need that some people have to seek thrills and take risks.

Share this:

- Share via email (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share to Google Classroom (Opens in new window) Google Classroom

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

By Emily Sohn

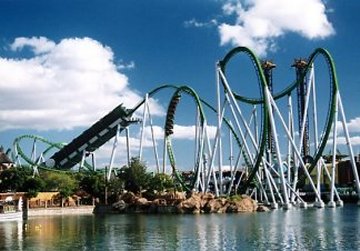

We tried to act calm. My friend Greg and I were waiting in line for the Incredible Hulk Coaster—a ride at the Islands of Adventure theme park in Orlando, Fla.

Every few minutes the roller coaster flew by, hurling its passengers upside down, whipping them from side to side, and shaking everything out of their pockets. Screams filled the air.

My insides churned. It had been years since I’d been on a roller coaster. “Why am I doing this to myself,” I wondered. “Why, in fact, do people go on roller coasters at all?”

|

|

The Incredible Hulk Coaster takes you on a wild ride.

|

| © 1999 by Joel W. Styer (http://www.ridezone.com ) |

“Where else in the world can you scream at the top of your lungs and throw your arms in the air?” Frank Farley asks. “If you did that in most other places, they’d take you to your parents and probably put you through a psychological evaluation.” Farley is a psychologist at Temple University in Philadelphia.

The freedom to act wildly is one reason why millions of people flock to amusement parks every year. Roller coasters are a major part of this attraction, and the people who run the parks keep looking for ways to make coasters taller, faster, and scarier.

The new Top Thrill Dragster at Cedar Point in Sandusky, Ohio, for example, rises 420 feet into the air and travels at speeds up to 120 miles per hour. It’s the tallest and fastest coaster in the world. And there’s no shortage of people willing and eager to ride it.

|

|

The Top Thrill Dragster at Cedar Point in Ohio is the world’s tallest and fastest roller coaster.

|

| Cedar Point |

Coaster appeal

For many people, there’s only one good reason to go to an amusement park: the roller coaster. Other people, however, would rather hide behind the closest candy stand than go near a coaster.

What separates these two types of people—those who seek thrills and those who prefer the quiet life?

Roller coasters often appeal to kids whose lives are stressful, structured, or controlled, Farley says.

“The summers of yore where kids could be kids and float down a river in an inner tube are over,” he says. “Roller coasters are a way of breaking out of the humdrum and expectations of everyday life. You can let it all go and scream and shout or do whatever you want.”

Attendance at amusement parks shows that many adults feel the same way.

Compared with skateboarding, extreme mountain biking, and other adventure sports, riding roller coasters is safe. Parents usually don’t mind when kids go on coasters.

Roller coasters also have a way of bringing people together. Riders share the thrill and adventure of surviving what feels like an extreme experience.

A matter of personality

Whether you like to ride a roller coaster may depend on your personality.

Farley suggests that, when it comes to thrill-seeking behavior, there’s a spectrum of personality types. At one extreme are risk-taking people who always seek out new experiences, whether the adventures involve skydiving, mountain climbing, or even coming up with new mathematical theories. Farley describes such people as having type-T personalities. “T” stands for thrill.

|

|

If you enjoy mountain or cliff climbing, you probably have a type-T personality.

|

At the other extreme are people who avoid risks and hate new experiences. Farley describes these people as having type-t personalities.

Most people lie somewhere in between, he says.

Some recent research has pinpointed genes that may drive some people to seek out new experiences. A gene is a tiny part of a chromosome, a component of living cells. Traits are passed from parent to offspring through genes. Genes determine, for example, a plant leaf’s shape, an animal’s mating behavior, or the color of your eyes.

The tendency to pursue adventure and adapt to new challenges was probably helpful when our ancestors first left Africa and started exploring the globe, Robert Moyzis says. He’s a biochemist at the University of California, Irvine.

Research by Moyzis and his coworkers has shown that a certain form of a gene called DRD4 is more common in people descended from ancestors who traveled long distances to settle new areas than in descendants of those who stayed behind.

This gene form is also more common in kids who have been diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) than in those who don’t have the disorder. Kids who have ADHD find it hard to sit still and pay attention and tend to act without thinking.

Genes, passed on from your parents and ancestors, may contribute to how you feel about riding roller coasters. However, past experiences and even the friends you hang out with also can influence your preference.

Extreme experiences

For many thrill seekers, roller coasters have a physical appeal, too. You feel things happen to your body that you don’t otherwise experience.

New technologies have allowed engineers to design coasters that change speeds quickly, shoot up hundreds of feet into the air, and make all sorts of twists. The forces on your body can be intense.

|

|

The Top Thrill Dragster at Cedar Point gives you a fast, twisty ride.

|

| Cedar Point |

Amazingly, for some people, even roller coasters aren’t thrilling enough.

Last year, Farley traveled to Nepal to interview people who had climbed Mt. Everest. It was the 50th anniversary of the first successful climb up the tallest mountain in the world.

“Climbing Mt. Everest is one of the riskiest things a person can do,” Farley says. He didn’t climb the mountain himself, but Farley has taken such risks as whitewater rafting in the Andes Mountains of South America and racing in hot-air balloons across China and Russia.

Farley interviewed 51 mountaineers, all of whom had reached the summit of Mt. Everest and returned safely, to find out what drives them to take such extreme risks.

“I want to find out what processes they went through to do what they did,” Farley says. “Most people can’t be Everest climbers, but they can push the envelope in their own lives. There may be clues in what these [mountaineers] do.”

You don’t have to climb Mt. Everest to benefit from a little bit of risk taking. If you get sick of school, become bored at home, or have a fight with a friend, one good answer may be to hop on a coaster. You’ll be screaming your head off in no time and sharing the experience with others!

Going Deeper: