Analyze This: Plants sound off when they’re in trouble

Clicks made by dry plants could help farmers monitor their crops

Microphones that pick up high-pitched sounds eavesdropped on plants in a new experiment. All sorts of plants, from tomatoes to cacti, made some noise.

Ohad Lewin-Epstein

Share this:

- Share via email (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share to Google Classroom (Opens in new window) Google Classroom

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

Plants may tell us when they’re in trouble.

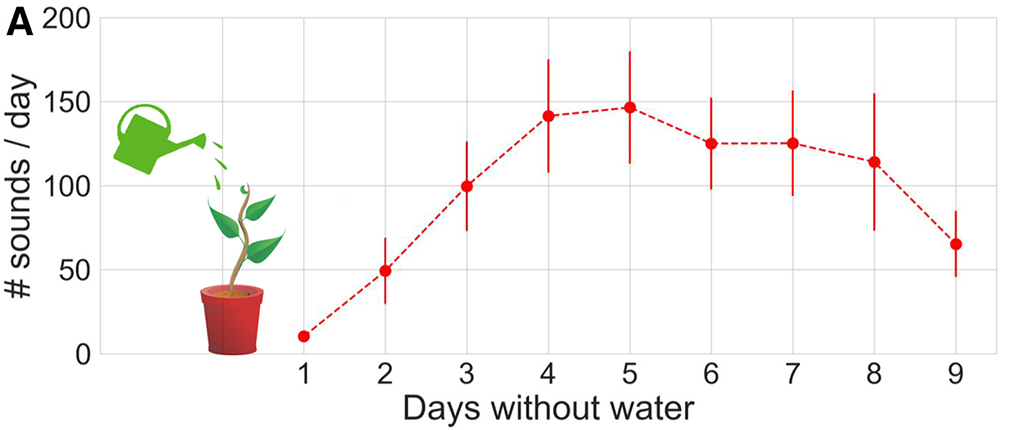

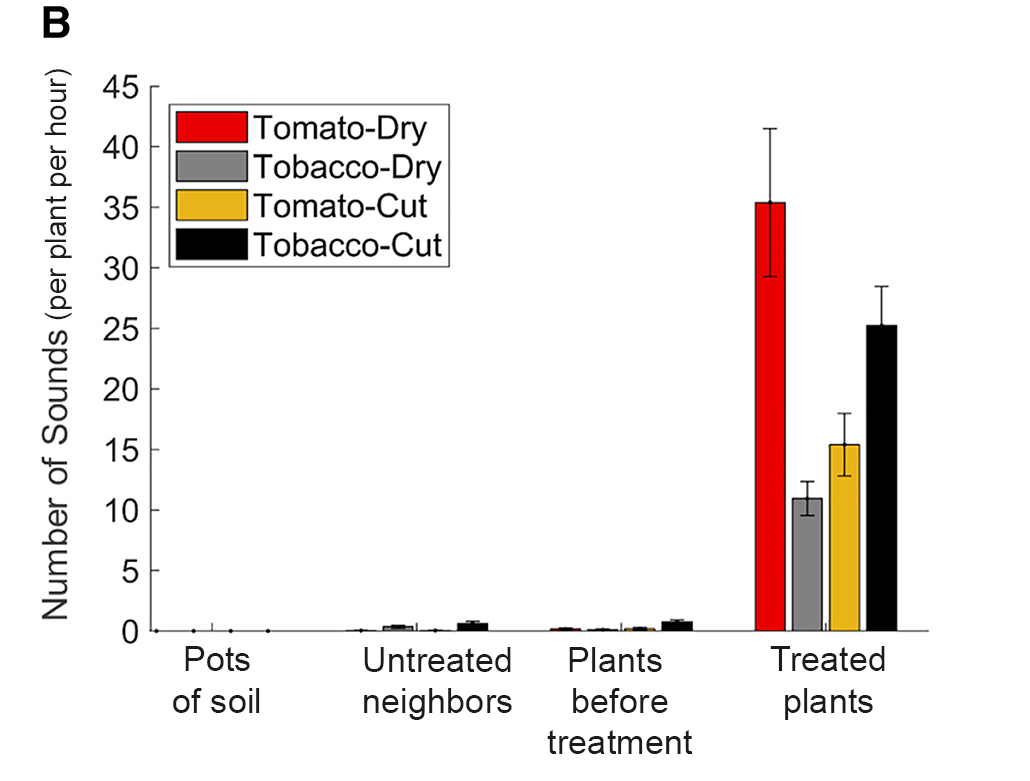

Thirsty tomato and tobacco plants make clicking sounds, researchers have found. The sounds are ultrasonic, meaning they are too high-pitched for human ears to hear. But when the noises are converted to lower pitches, they sound like popping bubble wrap. Plants also make clicks when their stems are cut.

It’s not like the plants are screaming, Lilach Hadany tells Science News. An evolutionary biologist, she works at Tel Aviv University in Israel. Plants may not mean to make these noises, she says. “We’ve shown only that plants emit informative sounds.”

Hadany and her colleagues first heard the clicks when they set microphones next to plants on tables in a lab. The mics caught some noises. But the researchers needed to make sure that the clicking was coming from the plants.

So, the scientists placed plants inside soundproofed boxes in the basement, far from the hubbub of the lab. There, microphones picked up ultrasonic pops from thirsty tomato plants. Though it was outside humans’ hearing range, the racket made by plants was about as loud as a normal conversation.

Snipped tomato plants and dry or cut tobacco plants clicked, too. But plants that had enough water or hadn’t been snipped stayed mostly quiet. Wheat, corn, grapevines and cacti also babbled when stressed out. These findings appeared March 30 in Cell.

The researchers don’t yet know why plants click. Bubbles forming and then popping inside plant tissues that transport water might make the noises. But however they happen, pops from crops could help farmers, the researchers suggest. Microphones, for instance, could monitor fields or greenhouses to detect when plants need water.

Hadany wonders whether other plants and insects already tune into plant pops. Other studies have suggested that plants respond to sounds. And animals from moths to mice can hear in the range of the ultrasonic clicks. Noises made by plants could be heard from around five meters (16 feet) away. Hadany’s team is now investigating how plants’ neighbors react to this chatter.

Data Dive:

- Look at Figure A. Over which days did the number of sounds from the tomato plants increase?

- How could you calculate the rate at which the number of sounds increases over the first four days?

- Look at Figure B. How do the treated plants (dry or cut) compare with their untreated neighbors? How do plants differ before and after treatment?

- Which plants made the highest number of sounds per hour?

- Why did the researchers record sounds from pots of soil alone?

- What animals do you think may be listening to plants’ sounds? What could they learn? How might this information be helpful to animals?