The ‘Doomsday’ glacier may soon trigger a dramatic sea-level rise

The ice shelf that had kept it in place could fail within five years

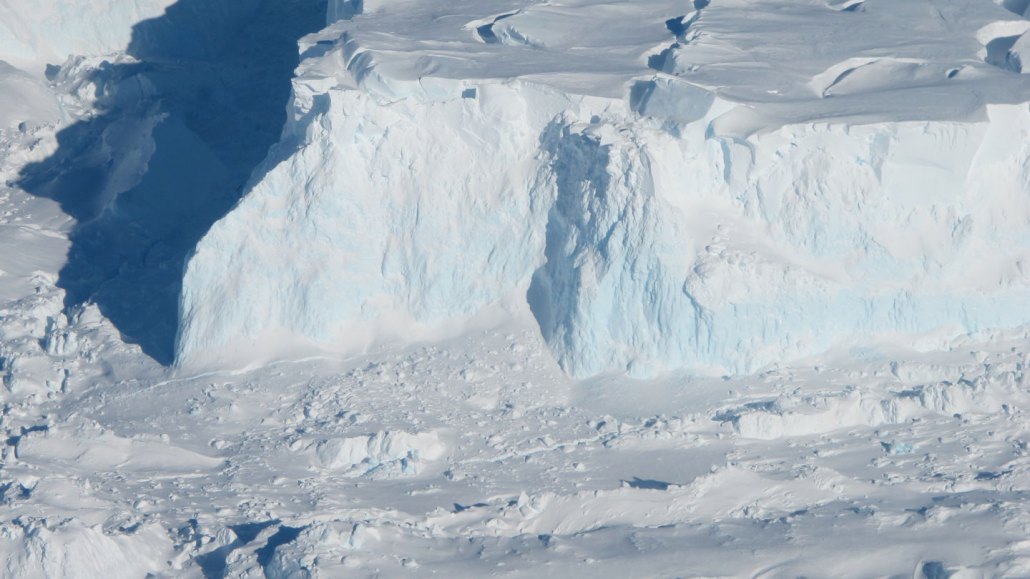

Thwaites Glacier (shown) is a Florida-sized slab of ice in Antarctica. This glacier is sliding into the ocean and poses the greatest near-term threat to sea level rise, scientists say. New data suggest that an ice shelf slowing the glacier’s slide may collapse within five years.

James Yungel/NASA

Share this:

- Share via email (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share to Google Classroom (Opens in new window) Google Classroom

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

A huge glacier in Antarctica is at risk of sliding into the ocean. If it does, that would trigger a disastrous rise in sea levels across the globe.

Thwaites Glacier is one of the biggest in Antarctica. Until now, an ice shelf — a floating slab of ice — has held this West Antarctic glacier from the ocean. But new research suggests this ice shelf could collapse within three to five years. An international research team shared its finding December 13 at the American Geophysical Union’s fall meeting. It took place in New Orleans, La.

Ted Scambos was part of that team. Thwaites spans 120 kilometers (75 miles) across. At roughly the size of Florida, he notes, “it’s huge!” Scambos studies glaciers at the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences. The organization is based in Boulder, Colo. If the whole glacier fell into the ocean, sea levels would rise by 65 centimeters (26 inches). That poses the world’s biggest threat to sea levels in the next 80 years.

The eastern third of Thwaites is currently propped up by a floating ice shelf. It’s an extension of the glacier — one that juts out into the sea. The underbelly of that ice shelf is lodged against an underwater mountain some 50 kilometers (31 miles) offshore. That sticking point has helped hold the whole mass of ice in place.

But new data suggest that brace won’t hold much longer.

Those data come from sensors placed beneath and around the ice shelf for the last two years. Scambos and his colleagues found that warm ocean waters are eating away at the ice from below. The ice shelf is losing mass. And that’s causing it to retreat inland. Eventually, it will retreat completely behind the underwater mountain that’s pinning it in place. Meanwhile, warm water is widening fractures in the ice. These cracks are swiftly snaking through the ice like cracks in a car’s windshield. As a result, the ice shelf is shattering and weakening.

This double-whammy of melting and shattering is pushing the ice shelf toward collapse. The whole thing could give way in as little as three to five years, Erin Pettit said at the meeting. Pettit, who was part of the research team, studies glaciers at Oregon State University in Corvallis. “The collapse of this ice shelf will result in a direct increase in sea level rise, pretty rapidly,” Pettit added. “It’s a little bit unsettling.”

Thwaites’ is nicknamed the “Doomsday Glacier.” That’s because of its potential to raise sea levels. But Thwaites’ collapse isn’t the only worry. Its fall would destabilize other West Antarctic glaciers. That could drag more ice into the ocean, raising sea levels even higher.

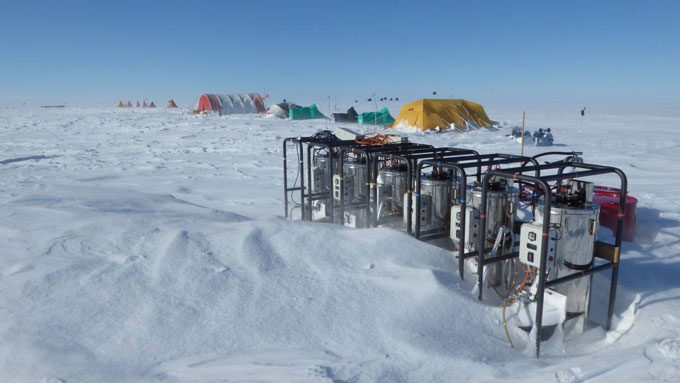

This makes Thwaites “the most important place to study for near-term sea level rise,” Scambos said. And that’s why in 2018, researchers from the United States and the United Kingdom started studying the glacier in-depth. This team planted instruments atop, within and below the glacier. They also placed sensors in the ocean near it. Data from these instruments alerted the researchers to the ice shelf’s near-collapse.

These data have led to other discoveries, too.

For instance, a second team of scientists has gotten the first look at ocean and melting conditions right at a glacier’s grounding zone. This zone is where the land-based glacier begins to jut out to become a floating ice shelf.

New data also show how the rise and fall of ocean tides can speed up melting. Tides do this by pumping warm waters far beneath the ice. These new findings promise to help scientists better forecast Thwaites’ future. “We’re watching a world that’s doing things we haven’t really seen before,” Scambos says. They happening, “because we’re pushing on the climate extremely rapidly with carbon-dioxide emissions,” he adds. “It’s daunting.”