How to prevent the robot replication apocalypse

Today’s bot-building robots aren’t after world domination. Next: keep future tech in check

Building self-replicating machines could lead to a future where robots can build more versions of themselves and cause harm to humans. But it’s not likely, scientists say.

cyano66/iStock/Getty Images Plus

Share this:

- Share via email (Opens in new window) Email

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share to Google Classroom (Opens in new window) Google Classroom

- Print (Opens in new window) Print

By Skyler Ware

Self-replicating robots — robots that can make copies of themselves — have a bad reputation. Blame movies. And books and video games.

For a long time, science fiction writers have imagined these robots as the bad guys. Think of Ultron building drone versions of himself to fight the Avengers. Or the Faro machines ravaging Earth in the Horizon video games. The robots are agents of destruction, designed to overwhelm our heroes.

But a self-replicating robot doesn’t have to be a bad thing. People use machines to build other machines all the time. Robots help build cars, medical instruments, microwave ovens, air conditioners — why not more robots? Now scientists are building self-replicating bots that could one day do all sorts of jobs humans can’t do. And with the right safeguards, those robots probably won’t take over the world.

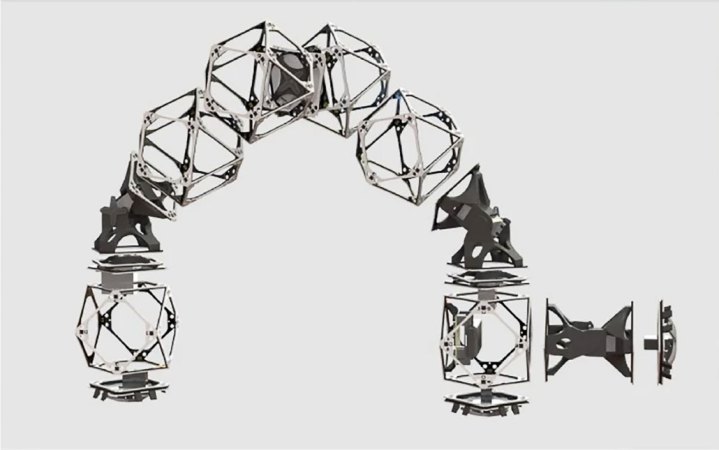

Amira Abdel-Rahman is a roboticist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge. She’s building self-replicating robots that can work in dangerous places, such as space. These robots work together like ants to build large structures or even bigger robots, piece by piece.

The robots are made of a few different parts that can be assembled with magnets in different ways, depending on what the robot needs to do. A typical robot, which looks and moves like a big inchworm, could lift and move parts from place to place and attach those parts to a bigger structure or robot. The bots could work together to build anything from airplanes to houses to structures in space.

Right now, Abdel-Rahman’s robots need some help to replicate. Each bot is built from premade parts. An existing robot connects those parts together to make a new robot. But someone has to make the parts ahead of time. The robots can’t go out into the wild and build new robots out of whatever they find.

They don’t, however, need a human to control the replication process. A computer program calculates how many robots are needed to build a structure. The program then tells each robot to start building the structure, a copy of themselves or even a bigger robot.

Robot revolution

Some people worry about what could happen when humans don’t have direct control over robots. Could the machines ever rise up against us?

Abdel-Rahman says that’s not likely for her creations. The robots she builds are programmed to do individual steps. They can’t think or act like humans do. In short, they don’t have artificial intelligence.

And because the bots need humans to build their parts, notes Hod Lipson, runaway replication — robots making too many copies of themselves — wouldn’t be an issue. Lipson is a roboticist at Columbia University in New York City.

But robot-building technologies could overcome those limitations at some point in the future. They could build parts of themselves from materials that other robots have collected. One day, the bots might not need humans at all. If that happens, we’d have a lot of questions to address, Lipson says.

First, we’d need to make sure that the robots’ values match human values. Here’s an example that helps to explain why this is important: Imagine a robot whose only job is making paperclips. The robot is incredibly powerful and advanced. We give it no instructions or limits other than that it needs to make paperclips. In the worst-case scenario, that robot could be so focused on making paperclips that it consumes everything on Earth. It could turn the whole planet into a great big pile of paperclips and paperclip-making machines.

This example, called the Paperclip Maximizer, might sound silly. But it illustrates why robots need guidelines. The paperclip-making robot wouldn’t know how important — or unimportant — paperclips are to humans. It wouldn’t know that humans value having a planet to live on more than we value having a pile of paperclips. It also wouldn’t necessarily know to prioritize what humans want over its own goals. We’d have to tell the bot what we care about most. The same applies for robots designed to make more robots, rather than paperclips.

Robots don’t have an inherent moral compass. Without guidelines, they might take actions we don’t agree with. Roboticists and philosophers call this the “value alignment problem.” For example, self-replicating robots might make more copies of themselves than wanted or needed.

The value alignment problem is difficult to address, says Lipson. But one possible solution is to show robots lots of examples of what we want. It’s like teaching kids, he says. “You shape [the robots’] experiences so they experience ethical behavior, and they pick it up from examples.”

Still, we can’t plan for every scenario in the real world, says Ryan Jenkins. He’s a philosopher at California Polytechnic State University in San Luis Obispo. He studies ethical issues surrounding robots and artificial intelligence. We can’t give a robot guidelines for everything it will ever experience, he says. “There’s always going to be things that come up in the real world that you hadn’t prepared for or couldn’t prepare for.”

So could self-replicating robots take over the world? Probably not anytime soon, says Jenkins. The thought “doesn’t keep me up at night.” But scientists and philosophers are devising more airtight ways to address these issues, he notes — just in case.