Saturn’s rings might be shredded moons

Data from the Cassini spacecraft show that the gas giant didn’t always have those iconic icy bands

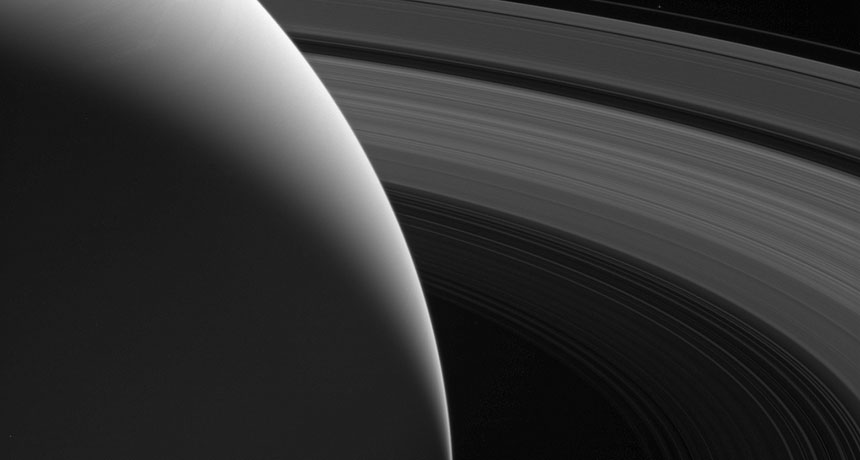

This image of Saturn’s rings was taken by NASA’s Cassini spacecraft on August 12, 2017. Cassini’s data now show that the rings are relatively young — a few hundred million years old at most.

JPL-Caltech/NASA, Space Science Institute

Share this:

- Share via email (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share to Google Classroom (Opens in new window) Google Classroom

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

NEW ORLEANS, LA. — Saturn’s iconic rings are a recent addition. That’s what astronomers now conclude after analyzing the final data collected last year by the Cassini spacecraft. The craft flew between the planet and its rings last year before plunging to its death within the gas giant’s atmosphere, last September. The rings are likely young, just a few hundred million years old. And they also appear far less massive than previously thought.

Such findings suggest the rings probably are the remnants of at least one now deceased moon. Earlier estimates had suggested those rings might have been ancient leftovers from the stuff that had formed the planet.

Scientists shared their new assessments on December 12 and 13, here, at the fall meeting of the American Geophysical Union.

For decades, scientists puzzled over the age and origins of Saturn’s rings. The planet formed some 4 billion years ago. If its rings had formed at that time, a constant bombardment of debris from the more distant solar system should have made the icy bands appear darker than they are. But scientists thought the rings were too heavy to have formed much more recently. That’s because there would have been less material available than in the solar system’s youth (from which Saturn could pull together those rings).

Cassini’s final orbits may have settled the issue. In the lead-up to the end of its mission, Cassini swooped between Saturn and its rings 22 times. Those daredevil moves let astronomers measure the difference in the gravitational tug on the probe from Saturn alone and from the rings-and-planet together.

These measurements revealed that the B ring — which makes up 80 percent of the total mass of the rings — is about 15 billion billion kilograms (33 billion billion pounds). That’s 0.4 times the mass of Saturn’s innermost moon Mimas (My-mus), reported Luciano Iess at the meeting. Iess is a planetary scientist in Italy at Sapienza University of Rome.

That’s lightweight enough to be young, agrees Larry Esposito. He had long proposed that the rings must be old. Esposito is a planetary scientist at the University of Colorado Boulder. He was not involved in the new work, but the topic has been an important one for him. In 1983, he estimated the rings’ mass — and got a similar answer to the new one — using data from the Voyager spacecraft. “But I always thought that was an underestimate,” he says of those earlier data. “I’m disappointed that they’re not more massive.”

Iess noted that there was an extra gravitational force nudging Cassini that is still not explained. That means the B ring could actually be as massive as two Mimases. But that’s still lighter than Esposito had hoped.

Dust raining down on the rings also supports the rings’ youth, Sascha Kempf reported on December 13. He’s a planetary scientist at the University of Colorado Boulder. Kempf and his colleagues used all of the debris that Cassini’s dust-counting instrument had detected since the spacecraft arrived at Saturn in 2004. These showed that the still-bright rings collect too much dust pollution to have retained their youthful shine for billions of years.

“Our data implies that the ring can only have a pollution age of a few hundred million years or so.” Concludes Kempf: “The rings are young.”

Taken together, the two results “really argue for young rings,” Esposito agrees. “That’s sent me back to square one.”

Riddle of the rings

How the rings formed remains a mystery. Esposito’s best guess is that a single moon about half the mass of Mimas was ripped up around 200 million years ago. That perfect timing is about as likely as hitting the jackpot in Las Vegas, Nev., he says. “We’re just really lucky to have developed intelligent life on Earth and launched a spacecraft to Saturn during the 200 million years when it happens to have rings around it,” he says.

Paul Estrada of the SETI Institute in Mountain View, Calif., worked with Kempf on the new analysis. He thinks ring formation might not be a one-off event. Instead, Saturn might go through cycles of moons and rings. Matija Ćuk also works at the SETI Institute. In 2016, he and his colleagues calculated that if a former outermost moon of Saturn had moved inward a bit, that motion could have destabilized the whole moon system.

If that happened, it could have forced the moons into orbits where Saturn’s gravity would have shredded them into the dust now orbiting as rings. Those rings might one day collect to form new moons. Eventually, they would go through the whole process again. Indeed, Estrada notes, this “could have happened many times.”