Weird star explodes over and over, cheating death

Oddball supernova lasts three years and blows off gas at least three times

A far-off supernova, shown in this artist’s illustration, might not be so ordinary. It could be a single star that exploded at least three times, each time blowing off lots of gas.

NASA, ESA, G. Bacon/STSci

Share this:

- Share via email (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share to Google Classroom (Opens in new window) Google Classroom

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

An exploding star in deep space refuses to die.

This supernova is named iPTF14hls. It has erupted continuously for the last three years. And it may have had two other outbursts in the past.

This tireless supernova could be the first example of a proposed explosion that involves burning particles and their oppositely charged counterparts within the core of a star. Or it could be something else. It could be something astronomers have never seen and don’t yet understand.

Scientists described this oddity in the November 9, 2017 Nature.

“A supernova is supposed to be a one-time thing,” says Iair Arcavi. He is an astrophysicist at the University of California, Santa Barbara. With such objects, the star is just supposed to explode. That’s it. “It’s dead. It’s done. It can’t explode again,” he notes. But not iPTF14hls. It’s “the weirdest supernova we’ve ever seen … It’s like the star that keeps on dying.”

Astronomers discovered it in September 2014 using the Intermediate Palomar Transient Factory. It scans the sky regularly with a telescope at the Palomar Observatory near San Diego. iPTF14hls looked like an ordinary type of supernova in a galaxy about 500 million light-years away. These explosions, called type 2 supernovas, mark the death throes of a star having a mass of between eight and about 50 times that of our sun. Typically these will glow for about 100 days before starting to dim.

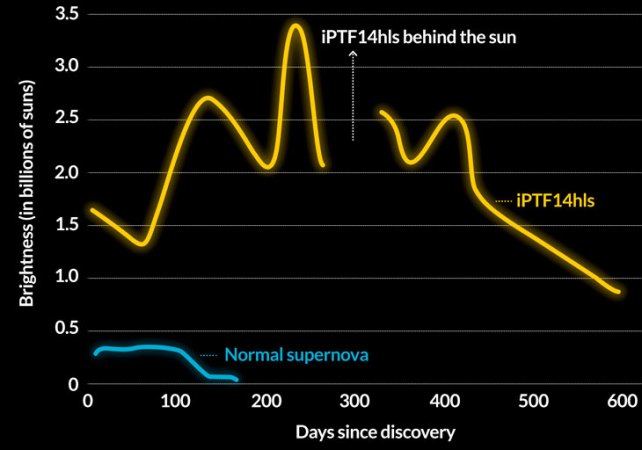

The first sign that iPTF14hls was unusual came a few weeks after its discovery. It started growing brighter. Then it dimmed. Then it brightened. The star went through at least five of those irregular cycles of brightening and dimming.

Story continues below graph.

And, there was something even stranger. Data collected from September 2014 to June 2016 show that the supernova remained bright for more than 600 days, Arcavi and his colleagues now report. Its eruption is only now showing signs of winding down. It may have already been in progress when it was discovered. If so, its explosive swan song may have been going on for even longer.

“That’s just unheard of,” says Stanford Woosley. He is a theoretical physicist at the University of California, Santa Cruz, who was not involved in the discovery. “Ordinary supernovae don’t do that!”

Normally, layers of gas get kicked out of an exploding star. When they do, they slow and cool as they expand. But iPTF14hls is different. It’s toasty — about 5,700° Celsius (10,292° Fahrenheit). This dying star maintained that temperature for the entire time it was observed. And its outer gas layers did not slow down as they should have. That means that this gas may have already cooled and slowed. It probably had been expelled in an earlier, superpowerful eruption. When? That eruption probably took place unseen between 2010 and 2014, the team suggests.

Story continues below image.

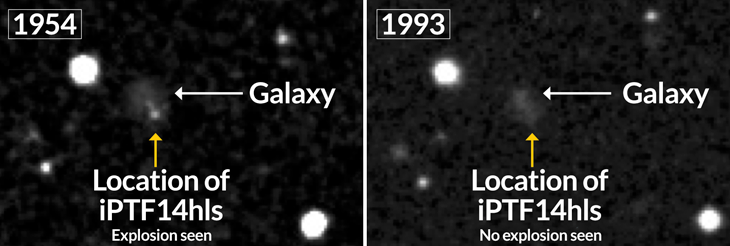

There’s some history to this star too. Data on photographic plates from the Palomar Observatory showed yet another bright burst in the same part of the sky in 1954. That might have been an earlier flash by this star.

Exploding again and again

How could a star explode over and over?

One theory suggests that stars between 95 and 130 times the mass of the sun can explode several times. To do so, a star must apparently get so hot that a lot of gamma rays — the most energetic form of light — zip about within it. Those gamma rays help to keep the star from collapsing under its own gravity. The star can get so hot, however, that its heat can transform gamma rays into electrons and their oppositely charged counterparts, positrons. Without internal energy from the gamma rays, the star’s core collapses and gets even hotter. That collapse can trigger a partial explosion, in which the star blows off a large share of its mass. But after this explosion, the electrons and positrons might recombine into gamma rays that can hold up the remaining stellar core.

The star can blow up this way several times, the idea goes. Finally, the fiery ball of gas dies in one last supernova. Eventually, its remains would collapse to create a black hole having about 40 times the mass of the sun.

But there’s a snag with this idea for iPTF14hls.

The theory predicts that such a star should blow off all of its hydrogen in the first explosion. iPTF14hls expelled 50 times the mass of the sun in hydrogen in the explosion in 2014. The amount of energy in the most recent explosion is also greater than it should be.

Woosley thinks the star could be a magnetar. These are highly magnetic, rapidly rotating stellar corpses. One could glow continuously for around two years. Still, that wouldn’t explain the 1954 eruption. Woosley says he hopes the most recent data will help determine which theory is right. Or, it could reveal that physicists need to come up with yet another explanation.

Either way, the show may be ending. The latest data show iPTF14hls is finally fading, Arcavi reports. As the outer layers of gas cool and become transparent, they could reveal whatever is at the explosion’s core. The team plans to just keep watching.

“I am not making any more predictions about this thing,” Arcavi says. “It surprised us every time.”