When every face is a stranger’s face

Scientists help people struggling with ‘face blindness’

Imagine agreeing to meet someone on a busy street, such as this one in New York City, and not being able to recognize that person by face. That’s the fate of many people with a condition known as prosopagnosia, also known as face blindness.

phillyskater/ iStockphoto

Share this:

- Share via email (Opens in new window) Email

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share to Google Classroom (Opens in new window) Google Classroom

- Print (Opens in new window) Print

Imagine watching a movie and not recognizing the characters from one scene to the next. Or not recognizing your friend after she gets her hair cut. Or struggling to know your family’s faces — even your own.

Many people grapple with these problems every day. Such people suffer from a medical condition known as prosopagnosia (Pro-so-pag-NO-shuh). Most people simply know it as face blindness. To be clear, affected people can see faces. And they’re not actually blind. They simply don’t recognize faces the way most people do.

You can experience what it’s like by looking at upside-down photos of celebrity faces. All the features are there: eyes, nose, mouth. But our brains can’t make immediate sense of those features the way they do when we view the photos right-side up.

The same thing happens in prosopagnosia. Affected people don’t see faces upside-down, but their brains similarly lack the ability to instantly recognize faces.

As many as two in every 100 people may experience face blindness, says Constantin Rezlescu. He’s a psychologist at Harvard University in Cambridge, Mass., who studies the condition.

Researchers are just starting to understand the disorder. They’re learning which areas of the brain are involved and studying what triggers it. Some therapists are even helping people cope. They’re offering alternative ways to identify people, and even therapy to improve face recognition.

Room full of strangers

Stop for a moment to imagine what it would be like to live with face blindness. When you look at John’s face, you can’t distinguish it from Joe’s. To identify them, you have to rely on other hints — hairstyle or color, height and weight, clothing or the way people walk. If you’re in a crowd, you might not even recognize your close friends. No matter where you go or who you are with, it’s as though you’re in a room full of strangers.

Some people are born with this condition. Others develop it after a brain injury, specifically one that damages the right temporal lobe. This brain area runs along the side of the head, just above the ear. It’s where the brain interprets what we see, letting us identify objects, including faces.

Some people with face blindness also have trouble identifying other objects — a specific house or car, for example. But many struggle only with faces. That suggests that the brain reserves a specialized pathway just to perform this task.

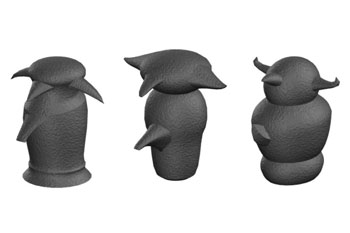

Rezlescu designed an experiment to test that. He asked people to look at “greebles.” These are meaningless, computer-generated objects. They’re meant to challenge the brain in a way similar to seeing a face, he explains.

The greebles in his study were grouped into families based on their overall shapes. Within each family, individual greebles differed from each other in small ways. This mimicked the way people within a family look more similar to each other than they do to unrelated people.

Rezlescu and his team worked with two people who had become face blind after suffering a brain injury. Another group of control subjects — people of similar age who were not face blind — also took part in the tests. The researchers showed each person a set of greebles, then evaluated how easily he or she could identify individuals among these made-up objects. They also asked each person to take a similar test, this time using photos of real faces.

As expected, the control participants had no trouble learning to identify faces. The two people with face blindness did. But everyone — including the two face-blind people — learned to identify greebles. That was true even when these characters looked very similar to other members of their greeble “family.”

These results offer strong evidence that the brain uses a different process to recognize faces than to identify greebles or any other object, Rezlescu concludes.

So some damage must have occurred to the brain’s face-recognition pathways in the two face-blind patients that he tested. But the more general pathways used to recognize other things, including greebles, were not. Exactly what processes had been damaged in the face-blind individuals remains a mystery.

Social struggle

Scientists have known about the kind of face blindness caused by brain injury for more than a century. It can happen when the brain cells used to identify faces are damaged. This might happen as the result of some accident, a stroke or carbon-monoxide poisoning. Suddenly, the person becomes unable to recognize faces — even those he has known for his entire life.

The face blindness that someone is born with — called developmental prosopagnosia — is a more recent discovery. But scientists are learning that this is actually the more common form.

The developmental type involves no damage to the brain. Instead, as a baby develops, its brain fails to build the pathways that should link up with the region needed to recognize faces. Because they have never lived any other way, children with this form of the condition — and even some adults — often do not realize that they see faces differently than others do. But at some point, many prosopagnosics do come to realize that they struggle far more than most others do to recognize people.

“Developmental prosopagnosia sometimes runs in families,” says Brad Duchaine. He’s a psychologist at Dartmouth College in Hanover, N.H. Such family links suggests there may be genes that influence this form of face blindness. But researchers still haven’t figured out which genes those might be.

Duchaine has worked with children and adults with face blindness. They try to compensate for their conditions by looking for other ways to recognize people, he notes. All of us use hair, voice, and the context in which we encounter people to help us identify them, he notes. But face-blind people use these clues much more than other people do. They also may rely on distinctive jewelry, the shape of a person’s face, or the color of their skin. In fact, he says, many people with face blindness have friends who are distinctive in some way. And that may be simply because these people were easier to recognize as their friendships were developing.

Even so, many kids with face blindness worry about misidentifying someone. It’s awkward, they say, to call someone by the wrong name. Flubs like this can put a strain on relationships, especially during the teen years. Many people simply avoid using names. Others pay close attention to what other people say to gather clues about a newcomer’s identity. And some report skipping school and other social events to avoid the frustration of not knowing who people are.

Improving recognition

Life with face blindness isn’t easy, in part because so few people understand the condition. Many people will feel snubbed and even resentful when they meet someone with face blindness and think they are being ignored by them. Those types of interactions can create stress with neighbors, classmates or workers.

That’s one reason researchers are working so hard to help people find ways to cope with their face blindness. One technique involves training the brain to recognize a small group of people that a face-blind individual may encounter daily. Over weeks to months, people with developmental face blindness train by viewing photos of these family members and close friends. Eventually, many show some success in recognizing those people. Some patients even say the exercise has helped them identify people not included in this training.

But such training doesn’t work for all people, cautions Sarah Bate. She’s a psychologist at Bournemouth University in Poole, England. Face-recognition training requires a large time commitment, she notes. People may spend hours keeping up their ability to recognize faces. And that’s simply not practical for everyone. So researchers are also helping people with face blindness learn to rely on features other than faces to tell people apart.

There seem to be different sub-types of face blindness, says Bate. Identifying them is the next step in Bate’s research. That might help researchers work more effectively with face-blind people, choosing the training style that might work best for each individual.

Bate and Duchaine are also looking into another tool for boosting face recognition: oxytocin (Ox-ee-TOW-sin). Our bodies produce this hormone when we hug or kiss someone. It helps us feel connected to other people and plays an important role in social situations.

People without face blindness get better at recognizing others when they inhale a dose of oxytocin. So Bate and Duchaine tried giving it to 10 people with face blindness. Each then tried two face-identification tasks. In one, they were asked to view and remember six faces. In the other, they had to find a target face in a group of three photos.

The prosopagnosics improved at both tasks after inhaling oxytocin. In contrast, inhaling a spray that lacked the hormone had no effect. But the improvement only lasted a few hours. And, in contnrast to earlier studies by others, here a control group of people without face blindness did not improve with oxytocin.

The scientists don’t yet know why oxytocin might improve face recognition. The hormone may directly affect the face-processing area of the brain, says Bate. Or it may boost the emotional impact of faces. Either way, it could be another tool to help individuals overcome their challenges.

If you don’t have face blindness, stop to think what it must be like to live with the condition before making insensitive remarks. People with prosopagnosia find it frustrating, for instance, when “normal” people complain about how hard it is to keep track of people, says Rezlescu. What they live with is a severe inability to recognize faces. It’s not periodically forgetting names or faces. While that may be embarrassing, it’s a normal part of everyone’s life.

If you think you may have face blindness, or know someone who does, there are resources to help. Faceblind.org (in the United States) or Prosopagnosia Research (in the United Kingdom) are good places to start.

Power Words

(for more about Power Words, click here)

adolescence A transitional stage of physical and psychological development that begins at the onset of puberty, typically between the ages of 11 and 13, and ends with adulthood.

carbon monoxide A toxic gas whose molecules include one carbon atom and one oxygen atom. (The “mono” in “monoxide” is a prefix from Greek that means “one”.) One common source: fossil-fuel burning.

control A part of an experiment where there is no change from normal conditions. The control is essential to scientific experiments. It shows that any new effect is likely due only to the part of the test that a researcher has altered. For example, if scientists were testing different types of fertilizer in a garden, they would want one section of it to remain unfertilized, as the control. Its area would show how plants in this garden grow under normal conditions. And that give scientists something against which they can compare their experimental data.

development (in biology) The growth of an organism from conception through adulthood, often undergoing changes in chemistry, size and sometimes even shape.

face blindness See prosopagnosia.

gene (adj. genetic) A segment of DNA that codes, or holds instructions, for producing a protein. Offspring inherit genes from their parents. Genes influence how an organism looks and behaves.

hormone (in zoology and medicine) A chemical produced in a gland and then carried in the bloodstream to another part of the body. Hormones control many important body activities, such as growth. Hormones act by triggering or regulating chemical reactions in the body.

oxytocin A hormone released by the body during hugging, kissing or touching. Oxytocin plays an important role in feelings of closeness to other people and even affection between a mother and child.

perception The state of being aware of something — or the process of becoming aware of something — through use of the senses.

prosopagnosia A disorder that prevents people from recognizing faces; also called face blindness. Someone with prosopagnosia is called a prosopagnosic. People with mild versions may lump together similar-looking people. In more severe cases, prosopagnosics may not recognize family members or even themselves. Most prosopagnosics use other features, such as hairstyle, clothing style or gait to identify people.

stress (in psychology) A mental, physical, emotional, or behavioral reaction to an event or circumstance, or stressor, that disturbs a person or animal’s usual state of being or places increased demands on a person or animal; psychological stress can be either positive or negative.

stroke (in biology and medicine) A condition where blood stops flowing to part of the brain or leaks in the brain.

temporal lobe A region of the brain where long-term memories are formed.