Whale pee is an ocean bounty

Migrating species can move valuable nutrients thousands of miles across oceans

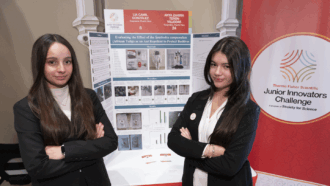

Whales like this right whale move nutrients around the ocean in their pee and poo. Whale poop moves nutrients from deep to surface water. Whales also move nitrogen from high-latitude waters thousands of miles when they pee in warmer winter breeding grounds.

Julian Gunther/Moment/Getty Images Plus

Share this:

- Share via email (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share to Google Classroom (Opens in new window) Google Classroom

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

By Laura Allen

Whale poop is loaded with nutrients. It’s one way these marine mammals move useful material around the ocean. But their liquid wastes are valuable, too. Some whales migrate thousands of miles, peeing out nutrients along the way, new data show. It’s yet another way they help keep ocean ecosystems healthy.

“I think of whales like gardeners,” says Joe Roman. He’s a marine biologist at the University of Vermont in Burlington. His work has shown how whales often move nutrients from deeper water (where many dine) to near the surface (where they poop).

But whales don’t just swim up and down. They can migrate long distances between oceans. In fact, some marine giants migrate further than any other mammals on Earth.

For instance, several whale species feed and fatten up in northern, nutrient-rich waters. This may be off the coasts of Alaska or Iceland. Later, they’ll travel thousands of miles south to their winter breeding grounds in Hawaii or the Caribbean. Here, in these warmer and nutrient-poor waters, they’ll give birth.

During their long migration and breeding season, these whales don’t eat. Or poop. They live off their blubber. And as they break down that fat for energy, extra water and nutrients are discarded in their pee.

And these animals pee a lot. But no one knew how many nutrients they released in these liquid wastes once they got to their winter habitat. Roman’s team decided to find out.

Whale wee fertilizes the sea

The researchers focused on gray, humpback and right whales. These toothless behemoths dine on tiny plankton, krill and small fish. (They filter this prey from the water using long, bristly, comb-like plates of baleen in their mouths.) To figure out how many whales there are and where they travel, the scientists looked up historic accounts. Then they compared it to data on whale sightings that people have been posting on websites.

To estimate the nutrients being moved by these whales, they started with a focus on the animals’ urine.

Whales are too large to study in captivity. So the researchers lacked data on how much nitrogen — a major nutrient — they shed in pee. To gauge this, they turned to another, smaller marine mammal that fasts before breeding: elephant seals.

In all, they now calculate, these three types of whales bring nearly 4,000 metric tons of nitrogen per year to their breeding grounds around Hawaii. That’s more than can be found in 2 million large bags of garden fertilizer! If true, this estimate means visiting whales may be doubling the available nitrogen while they’re there.

That extra nitrogen feeds phytoplankton at the base of the ocean food chain. As they grow, these tiny algae and bacteria absorb carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas. And that can help slow climate change.

Additional nutrients left by the visitors would come from the placentas of whales that just gave birth and from the bodies of whales that died in these waters.

All told, it’s like delivering “about 20 million Big Macs of food every year,” Roman says.

His team shared its new findings March 10 in Nature Communications.

“The surprising thing was how much nitrogen whales moved in urine,” Roman says. Whale pee was the largest source of this nutrient in their breeding waters. And before commercial whaling cut populations, migrating whales may have moved three times as much.

Whales shape their ocean home

“This is very nice work,” says marine biologist Carla Freitas Brandt. She works at the Institute of Marine Research in Bergen, Norway. It’s interesting because these whales don’t eat or poop during the breeding season, she says. “But they still excrete nutrients [from pee] in these regions, which is quite cool!”

Sean Johnson-Bice agrees. He’s a wildlife ecologist at the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg, Canada. He studies arctic foxes, which move nutrients to their dens. Poop and carcasses in their dens fertilize plants growing nearby. He says the new study shows the “remarkable contribution baleen whales make.” It’s further evidence of how valuable whales and other large animals can be within their ecosystems.

To Roman, there’s an important lesson here: Animals are “building the planet around us.” He hopes his team’s new research helps show the benefits of rebuilding populations of whales and other large species — including buffalo, which similarly move nutrients on land.

Do you have a science question? We can help!

Submit your question here, and we might answer it an upcoming issue of Science News Explores