How to invent a language — like that of Avatar’s Na’vi

Fictional languages are providing insight into real-world communication

Na’vi, the fictional people of the Avatar movies, speak a constructed language, or conlang. It’s one of many fictional languages that have been made for TV shows, movies, books and more.

MovTCD/Prod.DB/Alamy

Share this:

- Share via email (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share to Google Classroom (Opens in new window) Google Classroom

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

The distant moon Pandora from the Avatar movies is a richly immersive alien world. Dragon-like creatures prowl the skies. Supersmart whalelike beasts write poetry under the sea. Jungle plants glow multicolor in the dark. And Pandora’s native Na’vi people boast their own elaborate customs and language.

Most of this vivid world-building exists only on screen. But the Na’vi language is very real. In fact, some Avatar fans have learned to speak it.

Paul Frommer is the mastermind behind Na’vi. As a linguist at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles, he’s fascinated by the structure of languages. So when Frommer heard that director James Cameron was looking for someone to build a language for the first Avatar film, he jumped at the chance.

“What would it be like to create a language that people could actually speak, that would be entirely new?” Frommer wondered. “That was all tremendously exciting.”

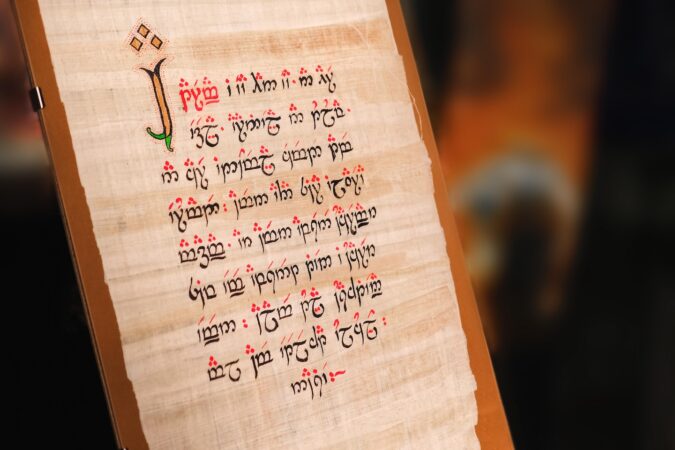

Na’vi is far from the only constructed language, or conlang, in fiction. Language scholar J.R.R. Tolkien famously created the Elvish tongues for The Lord of the Rings long before writing the books. Modern linguists like Frommer have come up with conlangs for all kinds of characters in books, TV and other media.

Creating a conlang involves far more than stringing together some made-up words. Languages are like machines, with many complex interlocking parts. Linguists must wield their expertise in these systems to invent ones that suit their fictional speakers. But language creation doesn’t just add depth to imagined worlds. It can also offer insight into the nature of language itself.

Making sound decisions

The most basic building blocks of any spoken language are sounds. So the first thing many language creators — or conlangers — do is nail down their sound system.

There’s an “incredible variety of speech sounds in the world’s languages,” Frommer says. And different languages use different subsets of those sounds. Deciding which ones to include in a conlang is like choosing spices to flavor a dish, he says. “You say, ‘OK, I want this to have kind of a Middle Eastern flavor, so I’m going to use these spices. I want it to have sort of an East Asian flavor, so I’m going to use those spices.’”

For Avatar, Cameron had already brainstormed the names for some characters and Pandoran wildlife. “It kind of had a bit of a Polynesian feel,” Frommer says. Polynesia is a region of more than 1,000 islands in the Pacific. Languages in this region often have voiceless consonants, such as “t” and “k,” but not the voiced versions of those sounds: “d” and “g.” Frommer followed the same rules in Na’vi.

Linguist Marc Okrand used a different strategy to create an alien language for Star Trek in the 1980s. In Star Trek films and TV shows, Klingons hail from a planet some 100 light-years from Earth. So Okrand wanted the Klingon language to sound unfamiliar to most Earthlings — especially English speakers.

To that end, Klingon boasts a combo of speech sounds not found together in any one world language — including several that don’t exist in English. One, written as [tlh], sounds sort of like the “dl” sound in “waddle.” Another, written as [H], is the harsh, throaty sound heard at the end of the German word “Bach” or in the middle of the Hebrew toast “l’chayim.”

Can you pronounce this?

[Q]

[tlh]

See if you can get your tongue around these Klingon sounds. To pronounce [Q], close your mouth as far back as possible, then force out air. To pronounce [tlh], place the tip of your tongue behind your top front teeth, like you’re about to say “t.” Then, without moving the tip, drop the sides of your tongue. This is the sound that starts the word “Klingon” in Klingon, which has no “k” sound.

Christine Schreyer faced the opposite challenge as Okrand when she crafted a conlang for the 2018 film Alpha. Since the movie is set in Europe around 20,000 years ago, Schreyer needed to create an authentic-sounding human language. But no one knows how people spoke back then.

“I looked at what are called proto-languages,” says Schreyer. She’s a linguistic anthropologist at the University of British Columbia’s Okanagan Campus in Canada.

Proto-languages are the estimated ancestors of modern languages. Scholars can sketch one out by comparing known languages. The common patterns among related tongues hint at what their common ancestor — the proto-language — was like.

Researchers had devised three proto-languages representing what people in Europe and Asia might have spoken around the time Alpha was set. Schreyer used a blend of the sounds from each in her conlang, Beama.

Some of Beama’s sounds exist in English. Others don’t. “It had ejectives, which are, like, more popping sounds,” Schreyer says. Such sounds are heard in some African and Indigenous American languages. Schreyer and a colleague described the work in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B in 2021.

Word-building

Armed with an inventory of sounds, a conlanger needs to come up with rules for the words in their language.

“Every language has rules about what can start its words, what can end its words,” Schreyer says. English, for instance, ends many words with “ng” but doesn’t start words that way. Some African and Asian languages — and Na’vi — do.

Languages also have distinct ways of linking sounds into syllables. English and Georgian — the language of the Eastern European country of Georgia — have many dense clusters of consonants. Hawaiian has more vowel-heavy syllables. Picking a conlang’s syllable structure helps define the language’s character. Beama mimics the vowel-heavy syllables in one of the proto-languages that inspired it.

Once they know how their sounds can fit together, a conlanger is ready to start building words. There’s not necessarily a rhyme or reason to this part. In real-world languages, Frommer says, “typically there is no relation between sound and meaning.”

Yet languages do have specific rules for how their words may shapeshift to fit different situations. In English, adding “s” can turn a singular noun plural. Adding “ed” can change a verb from present to past tense. The world’s languages offer conlangers a broad palette of inspiration for these kinds of changes.

Take nouns. They can be more than just singular or plural. “Nouns in Arabic distinguish singular from dual — exactly two of something — and plural,” notes David Peterson. He’s a conlanger based in Garden Grove, Calif. In creating the High Valyrian language for TV’s Game of Thrones, he gave nouns four different forms that depend on quantity.

Likewise, verbs can change based on tense. But they can also change depending on aspect, which marks whether an action is ongoing or complete. David Peterson and his wife, linguist and conlanger Jessie Peterson, found a creative way to do this in their language for the fire people in the 2023 animated film Elemental.

The basic form of a Firish verb is ongoing action. But adding the suffix “ksh” can mark it as complete. That suffix is based on a Firish verb that means to douse a flame — which is how the Petersons imagined that fire beings would describe something as being over.

Piecing together sentences

When it comes to arranging words into sentences, “there are certain top-level grammatical decisions you make,” David Peterson says. “Then you get progressively more complex.”

One top-level decision is noun and verb order. English usually has subject-verb-object order. A person (subject) creates (verb) a language (object). But it doesn’t have to be that way. To make Klingon as unusual as possible, Okrand gave it object-verb-subject order. That’s one of the least common among the world’s languages.

Once you start working with a specific noun and verb order, “certain other structures are going to suggest themselves,” Jessie Peterson says. One such structure involves words called adpositions. These describe the relationships between things: “to,” “in” and so on.

If a language has verbs before objects, as English does, its adpositions tend to come before its nouns. Something might be “in boxes.” But in languages in which objects come before verbs, such as Japanese, adpositions follow their nouns. “Instead of saying ‘in boxes,’ you would say ‘boxes in,’” Jessie Peterson says.

Following these types of rules can make a conlang more realistic. High Valyrian, for instance, puts adpositions after nouns to match its subject-object-verb order.

Deciding on word order is just the beginning of building out a language’s grammar. At first, a conlanger may come up with only enough grammar rules to translate the needed lines for a book, show or film. But no conlang is ever truly finished — the same way no natural language is ever done evolving.

Frommer, for example, still debuts new aspects of Na’vi on his blog. That includes some words suggested by fans who speak the language.

Do you have a science question? We can help!

Submit your question here, and we might answer it an upcoming issue of Science News Explores

Fictional language, real speakers

Days before the first Avatar movie premiered in 2009, Frommer received a shocking email. The long message was written by a stranger — entirely in Na’vi.

“My reaction was … ‘What? What is this all about?’” Frommer recalls.

It turned out a glossary of Na’vi words had leaked to the public. The emailer had studied that, along with interviews in which Frommer had described Na’vi grammar. “That gave me the idea that, yeah, this may very well catch on,” Frommer says. Indeed, a hub of Na’vi learners quickly gathered online — some of whom now speak the language more fluently than Frommer does.

Back in 2011, Schreyer got curious why so many people were studying a language designed for fictional speakers. When she surveyed Na’vi learners online, nearly 300 people from 38 countries, ages 10 to 81, responded. Some were big fans of Avatar and wanted to feel more connected to the film. Others were just fascinated by languages. Schreyer shared the findings in Transformative Works and Cultures.

“People were learning Na’vi so quickly,” Schreyer says. “I wondered how endangered language communities could replicate that.” Endangered languages are ones at risk of disappearing as their speakers die out or switch to speaking something else. This includes many Indigenous languages.

Schreyer has worked with members of the Taku River Tlingit First Nation in Canada to revitalize their ancestral language. After seeing how audio files, social media and other tools helped people learn Na’vi, Schreyer and her colleagues brought some of those ideas to a site for that helps people learn Tlingit words.

Na’vi is not the only conlang to draw real-world speakers. The nonprofit Klingon Language Institute has helped Star Trek fans study Klingon for decades. And as of last year, more than 400,000 English speakers had started Duolingo’s Klingon course.

Joseph Windsor, an expert in theoretical linguistics, estimates there are some 100 advanced Klingon speakers in the world today. He doesn’t count himself among them — though he knows enough to identify as a Klingon speaker on the Canadian census. (A census is an official count of a population.)

About a decade ago, Windsor decided to use Klingon to test the limits of language learning. He looked at a feature of language called stress. This is the emphasis that can be placed on different syllables to help distinguish a word’s meaning. It’s what sets the noun record apart from the verb record.

“Stress in Klingon, from a human language perspective, [is] completely unnatural,” says Windsor, who works at the University of Calgary in Canada. The rules for which syllables to stress are “really weird” and don’t follow the patterns seen in real-world languages. But when Windsor analyzed an 18-minute clip of seven advanced Klingon speakers talking, he found something surprising.

The speakers stressed Klingon syllables with 84 percent accuracy. This hints that it doesn’t matter how convoluted a stress system is. If there are regular rules to memorize, the human brain can pick it up pretty well. Windsor and a colleague shared the findings at a 2016 meeting of the Canadian Linguistic Association.

What makes a language

Conlangs may also help explore what our brains recognize as a language.

The brain processes real-world languages using areas in the frontal and temporal regions of the left hemisphere. This neural circuitry cares only about language, says Saima Malik-Moraleda. It doesn’t process other language-like means of expressing ideas, such as math or computer code.

Malik-Moraleda is a cognitive neuroscientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge. She and her colleagues wondered: Does the brain handle conlangs in the same way as real-world languages, which have evolved among groups of people over many generations? Or does it treat conlangs like other invented types of communication, such as code?

To find out, Malik-Moraleda’s team recruited 10 speakers of Klingon, eight Na’vi speakers, three people who knew High Valyrian and three who spoke Dothraki. (David Peterson also invented Dothraki for Game of Thrones.) In brain scans, people’s language centers lit up when they listened to recordings of the conlang they knew. Those brain regions were not as active when participants did non-language mental exercises. The team shared these findings in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in March.

The results offer clues to solving the mystery: “What makes a language a language?” Malik-Moraleda says. Maybe it is the ability to convey almost any meaning — including complex internal experiences, she says. Both conlangs and natural languages can do that. Math and computer code may not.

Conlanging 101

Conlangs designed to be spoken in books, TV shows and movies make up just a small fraction of the world’s invented languages. People have been conlanging for centuries. They’ve done it for journaling, art, international communication and more.

“There are thousands of language creators all over the world,” David Peterson says. “Most of them are doing it just because they love it.” Some hobbyists have designed languages expressed through gestures, musical notes or even knots.

You don’t need to be a linguist to get started, either. Jessie Peterson took her first crack at making a conlang when she was 10 years old. Growing up in rural Missouri, she says, “I was fascinated by other languages but never had access to them.” She made up a secret language to speak with her friends on the playground.

The key to becoming a good conlanger, the Petersons add, is studying many different languages. Especially unrelated languages. “Even if it’s not learned to any sort of fluency,” Jessie Peterson says. That’s easier now that people have access to the internet. Just sampling how different languages convey meaning “can really open your mind” to the possibilities for your conlang, she says.

“Then there’s just practice,” David Peterson says. “Create a language. Create it bad, and then create the second one better.”