Analyze This: Climate change may worsen the spread of ocean noise

Higher acidity and added meltwater could change how fast and far sound travels

Sounds from ships can roar through the ocean, stressing ocean animals. Because of how sound travels through water, climate change may make that noise louder.

Bugto/Moment/Getty Images

Share this:

- Share via email (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share to Google Classroom (Opens in new window) Google Classroom

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

From the rumble of boats to the din of oil drilling, sounds from human activity cascade across the oceans. This noise can bother ocean creatures. And climate change may make some spots even louder.

Researchers have expected the oceans to get noisier because of increasing human activity. “The more goods you buy, the more shipping you have, so the more noise you have,” says Luca Possenti. He studies sound in the ocean at the Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research in Texel. But Possenti and his colleagues realized that climate change might also influence how sound travels through the water.

Human-caused climate change is altering ocean temperatures, salt levels and acidity. So Possenti’s team used computers to model how those factors influence noise levels across the world’s oceans.

When waters become more acidic, they can’t absorb sound at some wavelengths as well, Possenti says. So those sounds can travel further, adding to the noise in some areas. This effect is relatively small. Other changes pump up the volume more, the researchers found. Changes to temperature and salt levels can alter how well different layers of the ocean mix. That, in turn, impacts how sound travels.

“We were surprised to see that actually there was a big change in the North Atlantic,” Possenti says. The team compared models of the world now to models of the world in about 70 years if climate change continues. In the North Atlantic, they saw a boost in sound levels in the upper 125 meters (410 feet) of the ocean.

This was caused mostly by ice melting off of Greenland, forming a chilly layer of water near the ocean’s surface. Sound traveling through water tends to bend toward the coldest area, Possenti says. As a result, sound waves tended to get stuck in the chilly top layer — spreading further out across the water, instead of traveling deeper. That increased the noisiness at this depth in the North Atlantic. The models suggested that a single ship could sound about five times as loud underwater because of this, Possenti says. The researchers shared their findings last October in PeerJ.

This bump in loudness is important because of all the ship traffic between Europe and North America, he says. The noise from that activity could make this area of the ocean even louder. That may stress animals, many of which communicate, hunt or navigate with sound. Marine mammals seem to avoid harbors because of the noise, Possenti says. “But if everywhere is going to get louder, we don’t know what is going to happen.”

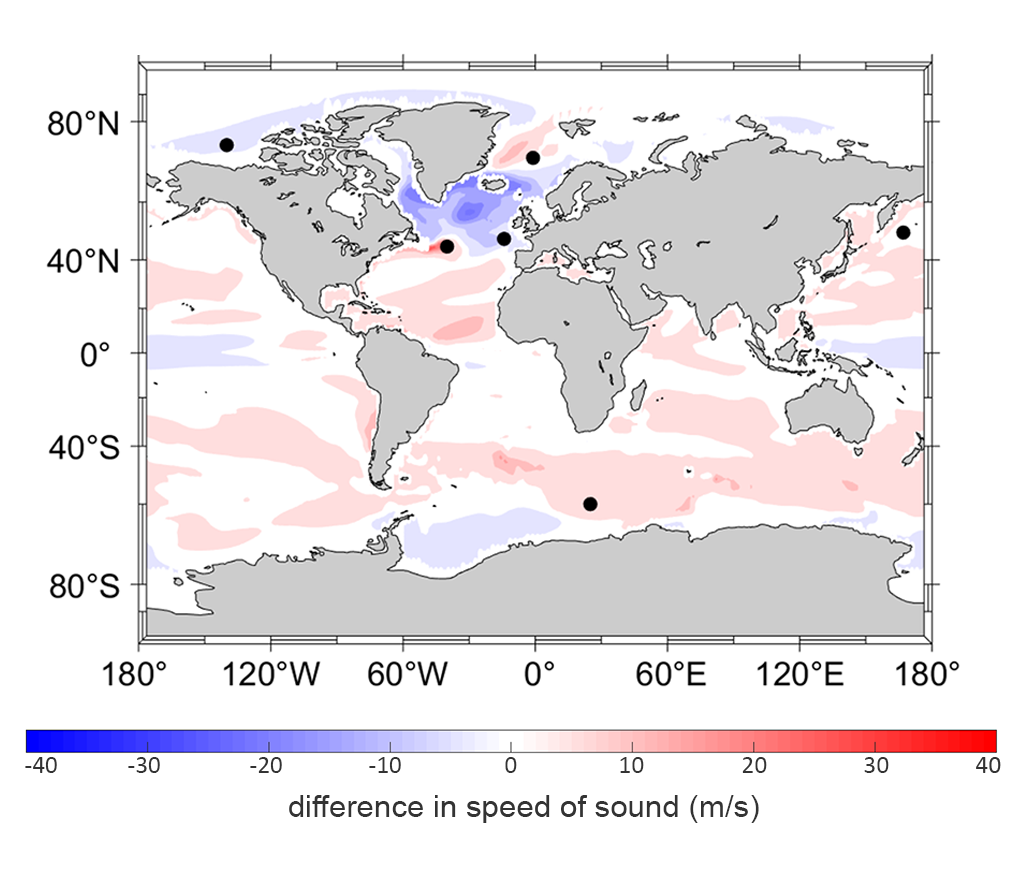

Loud(er) waters

Sound could travel differently through the ocean in the future, thanks to changes in wind speed and water temperature, salt levels and acidity. Researchers modeled the speed of sound 125 meters (410 feet) below the ocean’s surface around the world. They did this first for the years 2018 to 2022. Then they modeled how fast sound would travel at that depth in the years 2094 to 2098 if the world experiences moderate warming. This heat map shows the difference in sound speed between those two time periods. In their model, the researchers placed sound sources (black dots) at several spots near the coasts of continents.

Data Dive:

- What are some areas where sound may travel more slowly in the ocean in the future?

- What are some areas where sound may travel more quickly?

- How much more quickly will sound travel in the North Atlantic, between Europe and the United States?

- How might this picture change if the researchers placed the sound sources elsewhere in their computer model?

- Why would it be harmful for animals that communicate or navigate with sound to live in louder environments?