See the world through a jumping spider’s eyes — and other senses

How these spiders see, listen and taste differs greatly from how we sense the environment

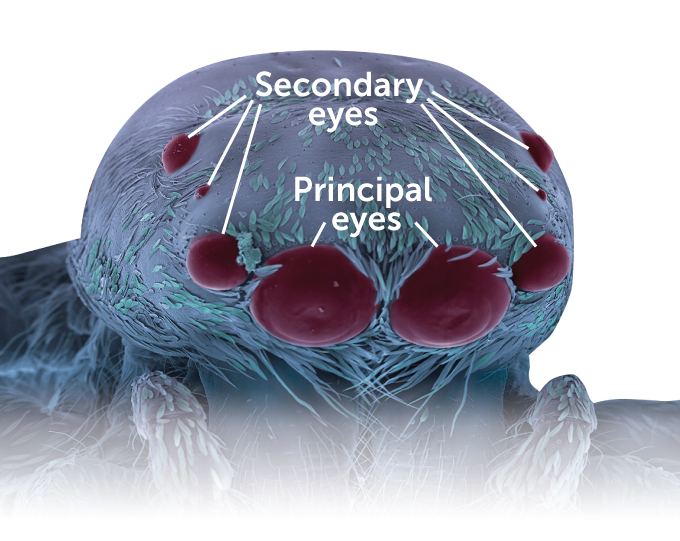

Jumping spiders have an exceptional way of sensing the world. While their two primary, front-facing eyes offer high-resolution color vision, side eyes give black-and-white vision that extends even to the area behind them. And their feet? They taste as they walk.

THOMAS SHAHAN

Share this:

- Share via email (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share to Google Classroom (Opens in new window) Google Classroom

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

By Betsy Mason

Imagine seeing the world largely in shades of gray — and a little blurry, too. But this view extends so far around to the sides that you can even make out dim shapes and motion behind you; no need to turn your head! The only color you see falls within a bright, X-shaped splash that moves with your gaze. At the center of this X, all is crisp and clear. It’s one small window of sharp, colorful detail in an otherwise gauzy gray world.

It’s a bit like watching a poorly focused black-and-white movie on a 3-D IMAX screen that wraps around the room. High-definition color appears only wherever you point a small spotlight.

This is the world of jumping spiders.

Their family includes more than 6,000 known species. Their two large front eyes make for adorable close-ups. But these spiders are best known for their hilariously flamboyant mating dances and their itty-bitty size. Indeed, some are smaller than a sesame seed.

Lately, scientists have been discovering there’s much more to these tiny arachnids than they had once realized. Through innovative experiments, researchers have been teasing out how these spiders see, feel and taste their environment.

“Part of why I study insects and spiders is this act of imagination that is required to really try to get into the completely alien world … and [the] perceptual reality of these animals,” says Nathan Morehouse. He’s a visual ecologist at the University of Cincinnati in Ohio.

Seeing the world from a spider’s view

Bees and flies have compound eyes. They merge information from their hundreds or thousands of lenses into a single mosaic image. But not the jumping spider. Like other spiders, its camera-type eyes more closely resemble those in humans and most other vertebrates. Each of these spiders’ eyes has a single lens that focuses light onto a retina.

The jumping spiders’ two forward-facing primary eyes have incredibly high resolution for creatures whose entire bodies usually span a mere 2 to 20 millimeters (0.08 to 0.8 inch). Yet their eyesight is sharper than that of any other spider. It’s also the secret to their stalking and pouncing on prey with impressive precision. Their sight is comparable to that of much larger animals, such as pigeons, cats and elephants. In fact, human vision is only about five to 10 times better than a jumping spider’s.

“Given that you can fit a lot of spiders in one single human eyeball, that is pretty remarkable,” says Ximena Nelson. “In terms of size-for-size,” she says, “there’s just no comparison whatsoever to the type of spatial acuity that jumping-spider eyes can achieve.” Nelson studies jumping spiders at the University of Canterbury. It’s in Christchurch, New Zealand.

That sharp vision, however, covers only a small portion of the spiders’ field of view. Each of those two principal eyes sees only a narrow, boomerang-shaped strip of the world. Together they form an “X” of high-resolution color vision. Beside each of these eyes is a smaller, less sharp eye. This pair scans a wide field of view, but only in black and white. They’re on the lookout for things that might need the attention of those bigger, high-resolution eyes.

On each side of the spider’s head is another pair of lower-resolution eyes. They let the spider watch what’s happening behind it. Taken together, the eight eyes offer a nearly 360-degree view of the world. And that’s a big advantage for a small animal that is both hunter and prey. Indeed, a jumping spider might consider our 210-degree field of view rather pitiful.

But in other ways, a jumping spider’s visual world is not so different from ours. The animal’s principal eyes and first set of secondary eyes together do basically the same job as our two. They couple low-resolution peripheral vision with high-acuity central vision. Like these spiders, we focus our attention onto a relatively small area and largely ignore the rest until something catches our attention.

Collaborative viewing

Each of the four pairs of eyes on a jumping spider has a different job. Yet they work together as a team. “I’m really interested in how [those] eyes collaborate,” she Elizabeth Jakob. A behavioral ecologist, she works at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Jakob uses an ophthalmoscope (Op-THAAL-muh-skoap). This type of device is usually used for peering into the back of the human eye. Hers has been modified to create an eye tracker for her spiders. With removable adhesive, she tethers a female Phidippus audax to the end of a small plastic stick. Then, she hangs the stick with its jumping spider in front of the eye tracker. Perched on a little ball, the spider faces a video screen. Once the spider is in position, Jakob plays videos. As the spider watches, Jakob records how those principal eyes react.

To do that, her tracker shines an infrared light at the retinas of those principal eyes. This creates a reflection. As the video plays, a camera records the reflection of the spider’s X-shaped field of view. That reflection will later be superimposed on the video the spider had been watching. This reveals exactly on what the spider’s principal eyes had been focusing. Watching the combined video affords people a portal through which they can begin to experience the spider’s visual world.

Jakob and her colleagues try to determine which objects viewed by the secondary eyes will prompt a spider to swing those principal eyes over for a sharper look. This test helps. It does more than just look at how the eyes work together; it also gets at what’s important to a jumping spider.

“It’s just so interesting to see what captures their attention,” Jakob says. It’s a “little window into their mind.”

Spider sight

This jumping spider watches videos of a cricket while an eye-tracker records where its principal eyes are focused. Then, researchers add other shapes in view of the spider’s secondary eyes. Only when they see a growing oval do the principal eyes shift their primary eyes — wary of a possible approaching predator.

First, the silhouette of a cricket — an appealing meal — appears on the screen. You can tell when the spider’s principal eyes have locked onto the cricket because the boomerangs start wiggling. They’re rapidly scanning the silhouette.

To find out what might draw the spider’s focus away from this potential meal, Jakob adds other images to an area of the screen that is within view of the secondary eyes. Any interest in a black oval? Nope. Maybe a black cross? Or another cricket? Not impressed. How about a black oval that is shrinking? Still no. What if the oval is getting bigger? Bingo: The boomerangs quickly flit over to the expanding oval to get a better look.

A jumping spider’s principal eyes can concentrate on preparing to pounce on dinner, while the other eyes notice and ignore any number of less important things. But if those secondary eyes spot something that’s getting bigger, well, that could be an approaching predator that demands immediate attention.

Their ability to warn is nifty — and a tactic that could make an easily distracted human jealous. “We’re swimming in a sea of potential stimuli all the time,” Jakob says. It helps to focus on important things, while ignoring others that likely aren’t. “This is certainly familiar to any human trying to focus on reading one thing.”

Jakob and her team described their findings April 16, 2021 in the Journal of Experimental Biology.

Spotlight on color

Humans and many other primates have exceptional color vision. Most people can see three colors — red, blue and green — and all the hues made from various combos of them. Many other mammals typically see just some shades of blue and green light. Many spiders also have a crude form of color vision, but for them it’s usually based on green and ultraviolet hues. This extends their vision into the deep violet end of the spectrum — well beyond what people can see. It also covers the blue and purple hues in between.

Some jumping spiders see even more.

While at the University of Pittsburgh in Pennsylvania, Morehouse led a team that learned certain species of these spiders have a filter squashed between two layers of green-sensitive light receptors. This allows the spiders to detect red light in a small area at the center of their principal eyes’ field of view. This adds red, orange and yellow hues to their world. That means their vision includes a broader rainbow of colors than we can see.

Seeing red can be handy since it’s often used as a warning. For jumping spiders, the ability to see red may have evolved as a way to avoid toxic prey. But once this new world of color was available to the spiders, Morehouse says, they put it to good use — in courtship.

Using Jakob’s eye tracker, Morehouse is investigating what interests female jumping spiders about the colorful, frenetic dances that males use to woo them. He’s finding that by playing to her various eyes, suitors employ a mix of movement and color to capture and hold a female’s attention.

She can see red, orange and yellow hues only at the center of her principal eyes’ boomerang–shaped view. Unless he can grab the attention of her secondary eyes with movement, she won’t turn her principal eyes toward him. And if she doesn’t, she may never see his fabulously colored features. For the male, this could be a matter of life and death. Why? An unimpressed female may decide to make a meal of him instead of a mate.

The males of one species Morehouse studies have a dazzling red face and beautiful lime-green front legs. Yet the females seem most impressed by the orange knees on the males’ third set of legs. When a male first spots a female, he raises his front legs like he’s directing a plane into its gate. Then he skitters side to side, hoping to catch the attention of her secondary eyes. When she turns his way, he comes closer and starts flicking the wrist joints at the end of his raised front limbs. You can almost hear him saying, “Hey lady, over here!”

Once he’s drawn her attention, out come the orange knees. These guys will “move them up behind their back into view in a kind of a peekaboo display,” Morehouse says.

To find out exactly what it is about a male’s display that turns a female’s head, Morehouse got clever. He doctored videos of males dancing, then played the videos to a female perched in an eye tracker. He used it to see how each of a guy’s moves affected her attention. If the male has an orange knee hiked up, but he’s not moving, she’s less interested. If those knees are moving but the orange color is removed, she’ll look but quickly lose interest. He’s got to have both the right look and the right moves.

“He’s using motion to influence where she’s looking, and then he’s using color to hold her attention,” Morehouse explains.

Behavioral ecologist Lisa Taylor of the University of Florida in Gainesville, likens the males’ tactics to those of human advertisers. “It feels like a lot of the tricks that marketers use to influence our decisions,” she says. “Understanding the psychology of spiders sometimes feels similar to understanding the psychology of humans.”

Can you feel it?

The male jumping spider’s leg-waving, knee-popping courtship spectacle is meant to capture a female’s attention. But this dance is only part of his show, Damian Elias discovered. He’s a behavioral ecologist at the University of California, Berkeley.

Many spiders use vibrations to communicate. A few reports had suggested jumping spiders were among them. When Elias investigated, he found a remarkably elaborate serenade of vibrations accompany the guys’ moves. The females feel those vibrations through the ground. It’s something humans would never perceive.

“It was a complete surprise to me,” Elias says. And when he shared what he had found with other spider scientists, he recalls, they too “were just blown away.”

To eavesdrop on these seismic songs, Elias uses a laser vibrometer. It’s a device similar to what’s used to measure vibrations in airplane components. He tethers a female spider onto a nylon surface that is stretched like a drumhead. Then he adds a male. When the male spots the female, he starts drumming his legs on the surface and vibrating his abdomen in a dance.

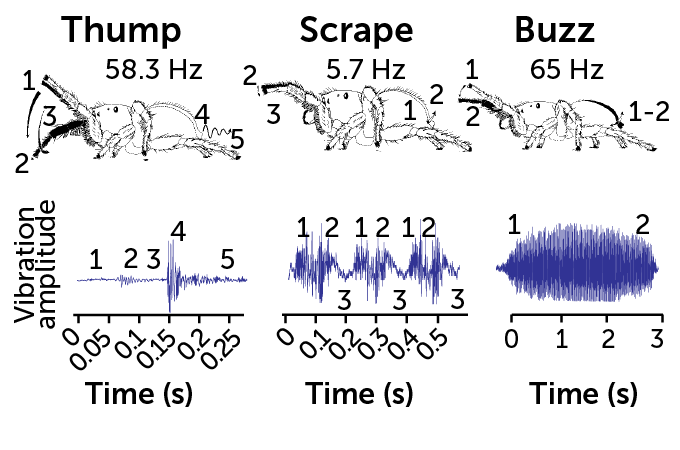

Elias measures the vibration of the nylon surface and translates it into something people can hear. This reveals an acoustic barrage of thumps, scrapes and buzzes. At the same time, Elias records video of the courtship in slow-motion. This lets him later study how the male’s sound and motion sync up. The male, he finds, performs what’s essentially a miniature drum solo — one perfectly matched to his flicks and kicks.

Without technology, Elias says, he could not have unlocked “this secret world.” His team described what it learned in the February 23, 2021 issue of the Journal of Arachnology.

The jumping spider’s world is filled with vibrations coming through the ground. But because those vibrations feel different depending on what the spider is standing on, things can change quickly as he hops from leaf to rock to soil.

In this way, the spiders’ entire sensory world is constantly changing. Yet they adapt without missing a beat.

Good vibrations

A male jumping spider works hard to get and keep a potential mate’s attention. He taps his front legs and vibrates his abdomen at various speeds (measured in hertz, or Hz). In this way, a male can produce thumps, scrapes and buzzes. Researchers can pick up these seismic signals with laser vibrometry.

Tasting the world with each step

The legs of jumping spiders also play a role in taste. Each foot contains chemical sensors. So they’re “tasting everything that they’re walking on,” Elias explains.

Very little is known about this aspect of the jumping spider’s senses. But the latest work out of Taylor’s Florida lab suggests that the males may be hoping to taste traces of potential mates.

Most jumping spiders don’t build webs to capture prey. Instead, they stalk and pounce. But as they travel, the spiders are constantly laying down a line of silk. It’s sort of a safety rope in case they fall or need to make a quick escape. And in their new study, Taylor and her colleagues found a male H. pyrrithrix spider could sense a female’s silk line when he stepped on it.

They’re now testing whether a male spider can detect if that silk trail was left by a female who might be willing to mate with him. Knowing that could be handy because if she had already mated, that female might view him not as a suitor but as lunch.

Taylor’s group shared its findings July 29, 2021 in the Journal of Arachnology,

“The more we learn, the more complicated it gets,” Taylor says. Jumping spiders “are so highly visual, and there’s so much vibrational stuff going on. And then the chemistry. It’s hard to imagine that [their world] wouldn’t just be super overwhelming.”

Yet jumping spiders manage this sensory deluge quite well. They live just about everywhere. You’ve most likely seen one, possibly in your own house. Despite being so small, they are easy to identify if you know what you’re looking for — or what they’re looking for.

“Next time you see a spider in the middle of a wall, and you look at it, and it turns back and looks at you, that’s a jumping spider,” says Nelson at the University of Canterbury. “It’s detected your movement towards it with its secondary eyes. And it’s checking you out.”

Jumping tigers

One thing jumping spiders use their amazingly good vision for is, well, jumping. These hunters don’t build webs. Instead, they stalk prey, then quickly and accurately pounce on it. During China’s Ming dynasty, more than 500 years ago, these spiders came to be known as “fly tigers.”

Scientists are now learning just how apt that nickname is. At least one group of jumping-spider species plans out strategic attacks. They can involve elaborate detours to reach a target. This type of clever hunting has typically been attributed to large-brained mammals, including real tigers.

“Some of the things that they do could keep you awake at night,” says Fiona Cross at the University of Canterbury. It’s in Christchurch, New Zealand. Cross and renowned jumping-spider expert Robert Jackson, also at Canterbury, have tested spiders in this group (including the clever species Portia fimbriate). They gave them all sorts of challenges in the lab.

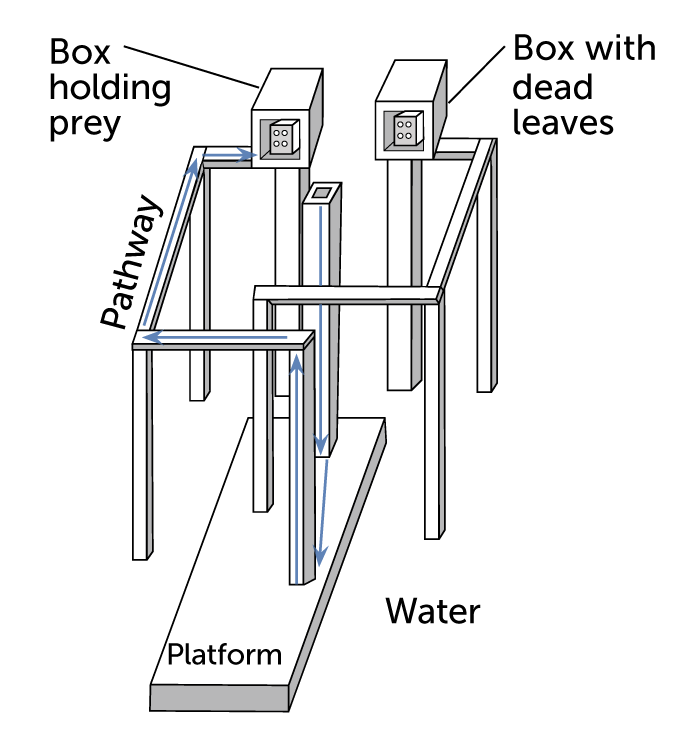

In one, they place a spider atop a tower on a platform (shown here) surrounded by water. Jumping spiders will avoid water whenever possible. From the perch, the spider can see two other towers. One is topped with a box containing prey. Another has a box of dead leaves. Both can be reached from the platform by a raised walkway with multiple turns. After viewing the scene, most spiders climb down the tower and choose the correct path to the target — even when that requires initially heading away from the target, losing sight of the prey, and first passing the start of the incorrect walkway.

This suggests these spiders are capable of planning, Cross and Jackson argue in a 2016 paper. The spiders come up with a strategy and then carry it out. — Betsy Mason