Video game violence

Playing violent video games may have harmful effects on the brain.

Share this:

- Share via email (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share to Google Classroom (Opens in new window) Google Classroom

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

By Emily Sohn

We read every message that readers submit to Science News for Kids, and we learn a lot from what you say. Two articles that really got you talking looked at video games. One story argued that video games can be good for you (see “What Video Games Can Teach Us”). The other argued that video games are bad for you (see “The Violent Side of Video Games”).

|

These stories ran 3 years ago, and we’re still hearing about them, almost weekly. In particular, those of you who enjoy killing people on screen disagree with research suggesting that your game-playing habits inspire you to act out.

“I have played the most violent games available on the market today,” writes Matteo, 15. “I don’t go killing people or stealing cars because I see it in a game. My parents say that, as long as I remember it’s a game, I can play whatever I want.”

Dylan, 14, agrees. “I love violent games,” he writes. “And I haven’t been in a fight since I was 12 years old.”

Akemi, now 22, says that he’s experienced no long-term effects in 14 years of gaming. “I have been playing the games since I was at least 7,” he writes. “I have no criminal record. I have good grades and have often been caught playing well into the night (that is, 4 hours or more).”

Despite what these readers say, many scientific studies clearly show that violent video games make kids more likely to yell, push, and punch, says Brad Bushman. He’s a psychologist at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

Bushman and his colleagues recently reviewed more than 300 studies of video media effects. Across the board, he says, the message is clear.

“We included every single study we could find on the topic,” Bushman says. “Regardless of what kids say, violent video games are harmful.”

TV watching

TV has been around a lot longer than video games, so researchers have more data on the long-term effects of violent TV shows on people than they do on the effects of violent video games.

|

In one study, scientists at the University of Michigan recorded the TV-watching habits of hundreds of first and third graders in 1977. Fifteen years later, the researchers looked at what kind of adults these kids had become.

By the time they were in their early twenties, women who had watched violent shows as kids were four times as likely to have punched, choked, or beaten other people as were women who didn’t watch such programs as kids. Boys who watched violent TV grew up to be three times as likely to commit crimes as boys who didn’t watch such programs.

But that doesn’t mean that everyone who watched violent programs ended up being violent themselves. It was just more likely to happen for some people.

In action

Violent playing is even more powerful than violent watching, Bushman says. Maneuvering through a game requires kids to take action, identify with a character, and respond to rewards for rough behavior. Engaging in such activities reinforces effective learning, researchers say.

|

In the game Carmageddon, for example, players get extra points for plowing over elderly or pregnant pedestrians in creative ways. Players hear screams and squishing sounds.

“In a video game, you naturally identify with the violent character, and identification with violent characters increases aggression,” Bushman says. “You’re the person who pulls the trigger, who stabs, who shoots, who kicks. You must identify with the aggressor because you are the aggressor.”

Now, I know what some of you are thinking: Maybe people who are already violent to begin with are the ones who seek out violent media.

“Video games may have an influence on human behavior or mentality, but I believe that whoever plays the game already has . . . a violent intent or nature within,” writes Jason, 16. “I strongly doubt a nun whom you could somehow get to play Mortal Kombat for a while would eventually gain a violent personality or behave as such.”

Jake, 15, says, “I think it depends on how the kids were raised more than anything, and if people try to play life like a game then they are IDIOTS.”

But the University of Michigan study of TV watching found that people who were more aggressive as kids didn’t necessarily watch more violent shows as adults. This finding suggests that watching violence leads to acting violently, not the other way around.

Inflicting punishment

In some of Bushman’s studies, kids are randomly assigned to play either a violent video game, such as Killzone or Doom 3, or an exciting, but nonviolent, game, such as MarioKart or a Tony Hawk skateboarding game, for about 20 minutes.

Then, each participant competes with a kid in another room on a task that challenges both players to press a button as quickly as possible. The winner gets to punish the loser with a blast of noise through a pair of headphones. The winner decides how long the noise will last and how loud it will be on a scale from 1 to 10.

In one of these studies, players were told that blasting their partners at level 8 or above would cause permanent hearing damage. (For safety reasons, the invisible competitor in this study was imaginary, but the setup made participants believe that they actually had the power to make another person suffer a hearing loss.)

The results showed that kids who played violent games first, then went to the task, delivered louder noises to their competitors than did kids who played nonviolent games first. Kids who played violent games and felt strongly connected to their on-screen characters sometimes delivered enough noise to make their invisible partners go deaf.

Because kids in these studies don’t get to choose which games they play, it seems clear that playing violent games directly causes aggressive behavior, Bushman concludes.

And that aggressive behavior may appear not as criminal activity or physical violence but in more subtle ways in the ways people react to or interact with other people in everyday life.

Brain studies

Some scientists are looking at kids’ brains to see how video games might affect their behavior. In one recent study, researchers from the Indiana University (IU) School of Medicine in Indianapolis assigned 22 teenagers to play a violent game for 30 minutes. Another 22 kids played a nonviolent, exciting game.

|

|

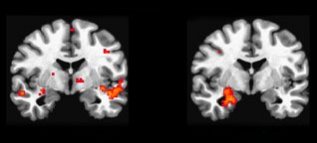

Brains scans show that the brains of teens playing nonviolent games (left) and those of teens playing violent games (right) have different patterns of activity. Those who played violent games showed greater activity in a region of the brain associated wit

|

| Indiana University School of Medicine |

Then, participants entered a special scanner that measured activity in their brains. For the next hour or so, the teens had to react to mind-bending tasks, such as pressing the “3” button when presented with three pictures of the number “1,” or pressing the “blue” button when presented with the word “red” written in blue letters.

The results showed that a part of the brain called the amygdala was especially active in players in the violent-game group, especially when follow-up tasks required them to respond to loaded words, such as “hit” and “kill.” The amygdala prepares the body to fight or flee in high-stress situations.

Moreover, among players in the violent-game group, a part of the brain called the frontal lobe was less active. The frontal lobe helps us stop ourselves from hitting, kicking, and performing other aggressive acts.

Frame of mind

Findings such as these don’t mean that every kid who plays Grand Theft Auto will end up in jail, researchers say. Nor do they suggest that video games are the single cause of violence in our society. From the brain’s point of view, however, playing a violent game puts a kid in a fighting frame of mind.

“Maybe [kids have] figured out ways to control this but maybe they haven’t,” says IU radiologist Vincent Matthews, who led the brain-scan study.

“If they look at their behavior more closely, they may be more impulsive after they play these games,” he adds. “There’s a lot of denial in people about what their behavior is like.”

Matthews now wants to see how long these brain changes last and whether it’s possible to change the brain to its original state.

|

|

Brain-scan studies at Michigan State University showed that playing violent video games leads to brain activity associated with aggressive thoughts.

|

| Courtesy of Michigan State University |

Danger zone

It’s important that kids understand the risks of violent media, Bushman says. Studies show that virtual fighting is just as likely to make a kid act aggressively as is drug abuse, a troubled home life, or poverty.

“The link between violent media and aggression is stronger than the link between doing homework and getting good grades,” Bushman says. “These games are not good for society.”

Government agencies and medical organizations have been warning parents and kids about the dangers of violent media for decades. Like smoking and fast food, Bushman says, violent games are a danger we would all be better off without.

We look forward to hearing what you have to say.

Comments:

It took me a long time to go through all your responses to our last video game story (“The Violent Side of Video Games”), and I learned a lot. Many of you, for example, pointed out correctly that I should have played the games I wrote about first, or at least researched the details. I apologize for making mistakes in the way I described certain games. In retrospect, I wish I had been able to give them a try.

What interested us most about your comments was how long, thoughtful, and even emotional they were. The subject obviously struck a nerve. Lots of you pointed out that video games come with ratings, like movies do. You said that parents should take responsibility for keeping their young children away from M-rated games. Many of you argued that kids can and should be able to tell the difference between real life and make-believe. An overwhelming number of respondents found it hard to believe that there is a link between video games and violent behavior because they themselves are not violent people.

Carefully designed research studies are the best way to distinguish between personal opinion and scientifically solid facts. I tried to address both in this next story, and I’m sure you’ll let me know how well I did. In the meantime, here are some of your thoughts from the last time we covered this topic. (I touched up spelling and grammar errors, but left your thoughts intact.)

I’m eager to hear what you have to say next.—Emily

Yes, video games desensitize people, but so do movies and television shows. Blaming children being violent on games and such isn’t right. Parents who are too busy living their own lives to pay attention to their kids are to blame more than games, because that’s all they are—games. Soon, someone will say that playing cowboys and Indians, or playing with toy soldiers, is bad for young children.—Akemi, 22

I have been playing video games for a large majority of my life. I (as with many of my friends) do not like these violent video games because they are violent, but because they create a great form of competition between my friends and me.—Curtis, 17

I think that while, yes, video games may contribute to violence, there are many other factors for the kids to allow the violence to affect them.—Heather, 16

www.pbs.org/kcts/videogamerevolution/impact/myths.html: go there and read it. Video games don’t cause violence, society does.—Bob, 16

OMG you were so wrong about GTA3. You only do what they tell you, you earn money and pass missions. But I do admit that these games make me more violent!—Stacey, 14

People in the Middle Ages were chopping each other’s heads off and they didn’t have any TV. They didn’t play Mario.—Jhamal, 16

After reading this article, I too have to express my opinion in that the choices for the video games were bad choices in conducting this experiment! If you are looking for violent video games, try Doom 3, God of War, or Mortal Kombat. They have . . . blood and gore present and produce more of a challenge. Simply having stylized action fighting doesn’t necessarily make it violent.—Matt, 19

I’ve experienced a lot of violence during video games because of repetitiveness rather than the actual gore itself. I’m so used to [first person shooter] games that I can play the game, killing people, without any sort of violence whatsoever. . . . It’s when you repeat the game for 2 yrs. straight that short bursts of aggression are visible.—David, 15

More Comments on “The Violent Side of Video Games”

Word Find: Video Game Violence

Going Deeper: