agriculture: The growth of plants, animals or fungi for human needs, including food, fuel, chemicals and medicine.

array: A broad and organized group of objects. Sometimes they are instruments placed in a systematic fashion to collect information in a coordinated way. Other times, an array can refer to things that are laid out or displayed in a way that can make a broad range of related things, such as colors, visible at once. The term can even apply to a range of options or choices.

bacteria: (singular: bacterium) Single-celled organisms. These dwell nearly everywhere on Earth, from the bottom of the sea to inside other living organisms (such as plants and animals). Bacteria are one of the three domains of life on Earth.

chemistry: The field of science that deals with the composition, structure and properties of substances and how they interact. Scientists use this knowledge to study unfamiliar substances, to reproduce large quantities of useful substances or to design and create new and useful substances.

chromatography: Separation and detection of chemical compounds as a result of their having traveled at different rates according to their different attractions to the matter that carries them (such as a flowing liquid or gas).

colleague: Someone who works with another; a co-worker or team member.

compound: (often used as a synonym for chemical) A compound is a substance formed when two or more chemical elements unite (bond) in fixed proportions. For example, water is a compound made of two hydrogen atoms bonded to one oxygen atom. Its chemical symbol is H2O.

consumer: (n.) Term for someone who buys something or uses something. (adj.) A person who uses goods and services that must be paid for.

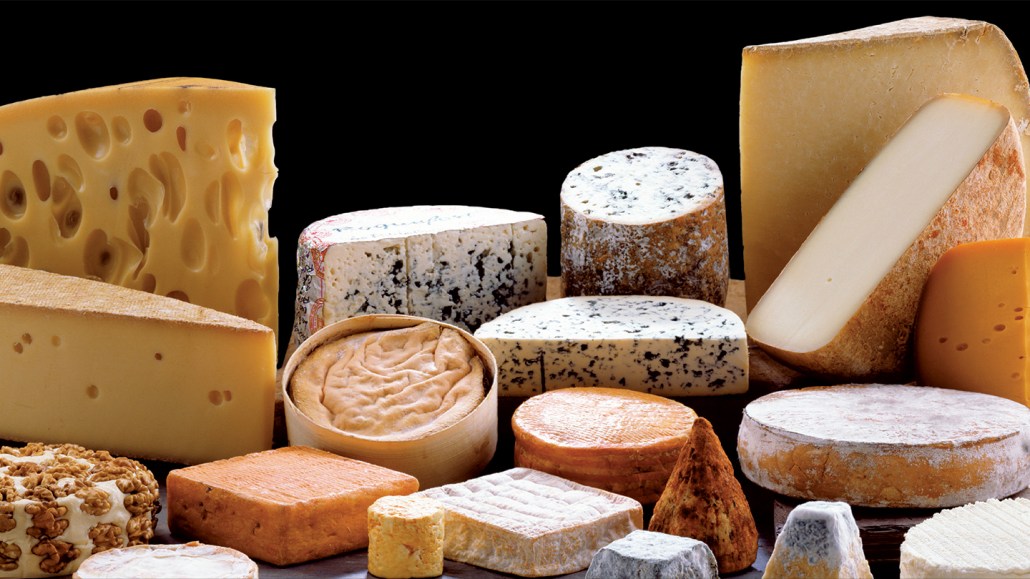

dairy: Containing milk or having to do with milk. Or a building or company in which milk is prepared for distribution and sale.

develop: To emerge or to make come into being, either naturally or through human intervention, such as by manufacturing. (in biology) To grow as an organism from conception through adulthood, often undergoing changes in chemistry, size, mental maturity or sometimes even shape. (as with towns) The conversion of wildland to host communities of people. This development can include the building of roads, homes, stores, schools and more. Usually, trees and grasslands are cut down and replaced with structures or landscaped yards and parks.

factor: Something that plays a role in a particular condition or event; a contributor.

flavor: The particular mix of sensations that help people recognize something that has passed through the mouth. This is based largely on how a food or drink is sensed by cells in the mouth. It also can be influenced, to some extent, by its smell, look or texture. (in physics) One of the three varieties of subatomic particles called neutrinos. The three flavors are called muon neutrinos, electron neutrinos and tau neutrinos. A neutrino can change from one flavor to another over time.

genetic: Having to do with chromosomes, DNA and the genes contained within DNA. The field of science dealing with these biological instructions is known as genetics. People who work in this field are geneticists.

genus: (plural: genera) A group of closely related species. For example, the genus Canis — which is Latin for “dog” — includes all domestic breeds of dog and their closest wild relatives, including wolves, coyotes, jackals and dingoes.

link: A connection between two people or things.

mass: A number that shows how much an object resists speeding up and slowing down — basically a measure of how much matter that object is made from.

microbe: Short for microorganism. A living thing that is too small to see with the unaided eye, including bacteria, some fungi and many other organisms such as amoebas. Most consist of a single cell.

microbiology: The study of microorganisms, principally bacteria, fungi and viruses. Scientists who study microbes and the infections they can cause or ways that they can interact with their environment are known as microbiologists.

molecule: An electrically neutral group of atoms that represents the smallest possible amount of a chemical compound. Molecules can be made of single types of atoms or of different types. For example, the oxygen in the air is made of two oxygen atoms (O2), but water is made of two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen atom (H2O).

sea: An ocean (or region that is part of an ocean). Unlike lakes and streams, seawater — or ocean water — is salty.

spectrometry: An instrument that measures a spectrum, such as light, energy, or atomic mass. Typically, chemists use these instruments to measure and report the wavelengths of light that it observes. The collection of data using this instrument can help identify the elements or molecules present in an unknown sample.

spectrum: (plural: spectra) A range of related things that appear in some order. (in light and energy) The range of electromagnetic radiation types; they span from gamma rays to X rays, ultraviolet light, visible light, infrared energy, microwaves and radio waves.

sulfur: A chemical element with an atomic number of sixteen. Sulfur, one of the most common elements in the universe, is an essential element for life. Because sulfur and its compounds can store a lot of energy, it is present in fertilizers and many industrial chemicals.

taste: One of the basic properties the body uses to sense its environment, especially foods, using receptors (taste buds) on the tongue (and some other organs).

tone: (in acoustics) The pitch of a sound, especially for musical notes.