Comet probe may shed light on Earth’s past

If a comet lander survives, it could tell space scientists plenty about Earth’s earliest days

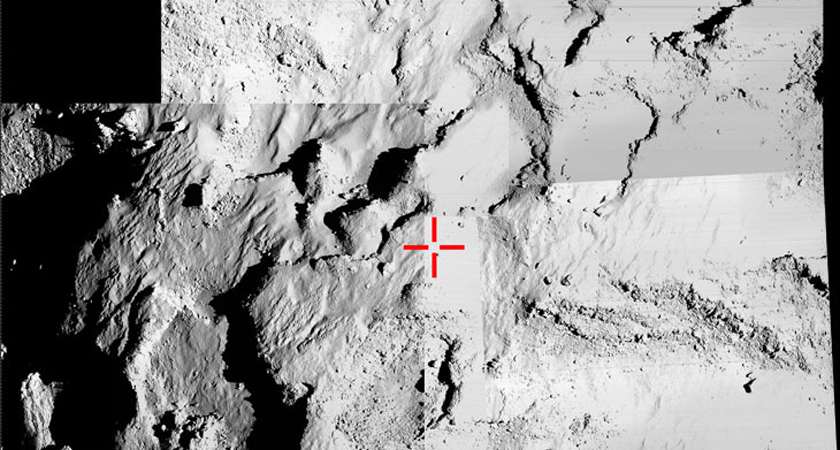

Philae initially came down precisely where it was supposed to (see red indicator) — but couldn’t stick its landing. After two hops, it landed somewhere else, still to be determined and partially in shadow.

ESA/Rosetta/MPS for OSIRIS Team MPS/UPD/LAM/IAA/SSO/INTA/UPM/DASP/IDA

Share this:

- Share via email (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share to Google Classroom (Opens in new window) Google Classroom

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

DARMSTADT, GERMANY Comets are rubble left over from the birth of the solar system. By studying these hunks of rock, dust and ice, scientists hope to better understand the early history of the solar system — including Earth’s early years. And never has the chance of doing this been better than on the comet under Philae’s robotic feet.

After a more than 10.5-year voyage, this robotic lander has just set down onto the surface of comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko. On November 12, the day it landed, Philae and its mother ship — the Rosetta spacecraft — were roughly 500 million kilometers (310 million miles) from Earth.

Several spacecraft had spent a few hours observing comets from on high as they flew by these mega-boulders. But until Philae’s landing, no mission had placed research instruments onto a comet. The robotic lander has already been sending back photos and probing the rock underfoot. Philae may even get to observe gases or other matter emerging from underground as the comet heats to scorching temperatures. And it will get beastly hot within a few months as the comet’s orbit swings it in close to the sun.

For now, scientists are trying to figure out precisely where Philae set down. Problems with a thruster kept the lander from holding fast on its first try.

Now, instead of being entirely in open space, as planned, the lander is flanked by what looks like a cliff. “We are not sure how far we are from the cliff, but we are in its shadow permanently,” says Jean-Pierre Bibring. A scientist at the Université Paris Sud in Orsay, France, he spoke at a media briefing on November 13.

The lander also is not sitting perfectly on all three legs, he noted. It is almost vertical, with two feet on the ground and one in open space.

Sitting in a cliff’s shadow also means the lander’s solar panels will get less sunlight than mission scientists had expected. The early data suggest that the lander is getting just 1.5 hours of sunlight per day. That is far less than the six to seven hours it would have gotten if it had landed exactly on target — which it did. At first.

On that first touchdown, Philae hit the bull’s-eye. But the lander didn’t stick its landing. Instead, it bounced twice. In between the first and second touchdown, the lander shot a kilometer up into space. In fact, it caught almost two hours of air time before it hit 67P again. The next bounce sent it 20 meters into the air for a 7 minute leap. Researchers are now trying to identify precisely where the lander now sits.

But Philae isn’t the only science center studying the comet. Its mother ship, Rosetta, arrived at 67 P on August 6, 2014. Immediately, that spacecraft began orbiting the comet and snapping pictures. Rosetta plans to stay with the relatively tiny celestial rock until at least December 2015. Scientists are hoping that throughout, Rosetta will be able to send back photos.

It also will relay back to Earth the data that Philae collects. But even if Philae had stuck its landing, the robot was not expected to remain active for more than about four months. As 67P nears the sun, it will heat up dramatically. Eventually, the lander’s instruments will essentially get fried.

What makes comets special?

Comets and asteroids are thought to be the oldest, most pristine relics of the early solar system. People can’t go back billions of years in time to the birth of the sun. So exploring comets and asteroids may be the best option for learning how the solar system evolved, explains Matt Taylor. He’s the Rosetta project scientist at the European Space Agency’s Science and Technology Center in Noordwijk, the Netherlands.

Studying the geology and chemistry of comets, he says, could give clues to how the planets evolved into what they are today. What’s more, they might also hint at where Earth got its water and certain other ingredients for life.

In other words, Taylor says, the potential payoff of this mission has been worth the hazards, costs, nail biting and decade-long wait for answers. At last, he notes, scientists can sit back and watch the data fly in.

Did space rocks supply Earth’s water?

Around 4.6 billion years ago, the solar system started to form as a giant cloud of gas and dust. Eventually, gravity forced them to collapse inward and coalesce. Most of this material got pulled into the center of the cloud to form the sun. The rest condensed into a handful of huge rocks that became planets. Smaller bodies became comets and asteroids.

In that scenario, asteroids probably formed between Mars and Jupiter. There it would have been too hot for water and ice to survive. Comets, on the other hand, probably condensed farther out in this embryonic cloud. In the frigid, dark edges of the solar system, ice would have been able to persist and start to attach to clumps of gas and dust, scientists believe.

Those outer reaches of the solar system include a region known as the Kuiper (KY-per) belt. Here, beyond the orbit of Neptune, lies a vast area or rocky debris left over from the formation of the solar system. Many of its objects are made of ice (frozen water), rock, frozen methane and ammonia. Even farther out, well beyond the orbit of Pluto, lies the Oort cloud. This zone of icy rocks has been suggested as the birthplace of many comets.

If comets formed in such distant places, they may have ferried lots more water to Earth than the asteroids did. At least, “That’s the conventional wisdom,” says Claudia Alexander. A leader of the U.S. arm of Rosetta, this NASA scientist is based at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. (NASA contributed electronics and three instruments to the Rosetta mission. At least one of these instruments will look at 67P’s water.)

Rosetta and Philae will give scientists a chance to virtually “get their hands on” the comet’s ice, says Alexander. That could help them figure out pretty quickly whether comets like 67P brought water to Earth billions of years ago.

One of the first things they’ll want to figure out: Is 67P’s water the same type that makes up Earth’s oceans? Most comets studied so far have possessed a larger amount of deuterium, an also known as “heavy hydrogen,” than Earth does. If 67P does too, that would argue against comets being the source of most Earthly water.

Indeed, such a finding might instead argue that asteroids were the main source. Scientists recently found at least one asteroid with water. Called Ceres — and large enough to be considered a dwarf planet — it orbits the sun on a path between Mars and Jupiter. This asteroid also spouts off water vapor, sort of like a comet.

To confuse matters further, Rosetta’s observations already indicate that 67P has many traits of an asteroid. This comet, for example, isn’t covered in surface ice. Instead, its water appears to be stored deeper within its core.

Such findings hint that comets and asteroids aren’t as radically different as scientists had once thought. Instead, Alexander says, they may fall on a continuum with rocky, dry asteroids on one end, really icy comets on the other and everything else in between.

As 67P approaches the sun, its ice will transform directly into water vapor and other gases. Along with dust, these gases will shoot outward. As these jets collide with other particles from the sun, the comet will develop two tails.

Unlike the showy tails of Halley’s comet in 1986, however, 67P’s tails will not be visible to the naked eye. But no problem. Rosetta will witness them from a front-row seat. As the comet’s tails grow, Rosetta will record the show — along with other details of how the comet morphs during its intense solar heating.

Power Words

asteroid A rocky object in orbit around the sun. Most orbit in a region that falls between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter. Astronomers refer to this region as the asteroid belt.

chemistry The field of science that deals with the composition, structure and properties of substances and how they interact with one another. Chemists use this knowledge to study unfamiliar substances, to reproduce large quantities of useful substances or to design and create new and useful substances. (about compounds) The term is used to refer to the recipe of a compound, the way it’s produced or some of its properties.

coalesce The bringing together of many small elements into a combined mass.

comet A celestial object consisting of a nucleus of ice and dust. When a comet passes near the sun, gas and dust vaporize off the comet’s surface, creating its trailing “tail.”

condense To become thicker and more dense. This could occur, for instance, when moisture evaporates out of a liquid.

deuterium An isotope of hydrogen which consists of a proton, neutron and electron. The proton-neutron nucleus is also referred to as deuteron.

embryo The early stages of a developing vertebrate, or animal with a backbone, consisting only one or a or a few cells. As an adjective, the term would be embryonic — and could be used to refer to the early stages or life of a system or technology.

evolve To change gradually over generations, or a long period of time. Nonliving things may be described as evolving if they change over time. For instance, the miniaturization of computers is sometimes described as these devices having evolved to smaller, more complex devices.

geology The study of Earth’s physical structure and substance, its history and the processes that act on it. People who work in this field are known as geologists. Planetary geologists study the same things about other planets and celestial bodies, such as asteroids.

gravity The force that attracts anything with mass, or bulk, toward any other thing with mass. The more mass that something has, the greater its gravity.

Kuiper belt An area of the solar system beyond the orbit of Neptune. It is a vast area containing leftovers from the formation of the solar system that continue to orbit the sun. Many objects in the Kuiper belt are made of ice, rock, frozen methane and ammonia.

lander A special, small vehicle designed to ferry humans or scientific equipment between a spacecraft and the celestial body they will explore.

Oort cloud A swarm of small rocky and icy bodies far beyond the orbit of Pluto, up to 1.5 light-years from the sun. The cloud is a source of some comets.

orbit The curved path of a celestial object or spacecraft around a star, planet or moon. One complete circuit around a celestial body.

orbiter A spacecraft designed to go into orbit, especially one not intended to land.

planet A celestial object that orbits a star, is big enough for gravity to have squashed it into a roundish ball and it must have cleared other objects out of the way in its orbital neighborhood. To accomplish the third feat, it must be big enough to pull neighboring objects into the planet itself or to sling-shot them around the planet and off into outer space. Astronomers of the International Astronomical Union (IAU) created this three-part scientific definition of a planet in August 2006 to determine Pluto’s status. Based on that definition, IAU ruled that Pluto did not qualify. The solar system now consists of eight planets: Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune.

pristine An adjective referring to something that is in original or near-original condition. It means something is somewhat old but in a seemingly “untouched” or unaltered condition.

relic Something that is a leftover from an earlier time. The term is usually applied to things that had been fashioned by people.

solar Having to do with the sun, including the light and energy it gives off.

solar system The eight major planets and their moons in orbit around the sun, together with smaller bodies in the form of dwarf planets, asteroids, meteoroids and comets.