Ancient jellyfish? Upside down this one looks like something else

Flipped around, it resembles a burrowing sea anemone

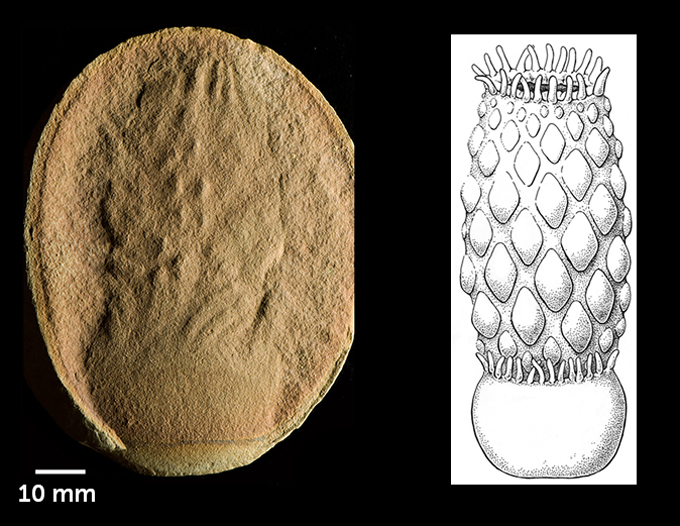

Based on fossils, some scientists thought the ancient animal illustrated here, called Essexella, was a jellyfish. But it may actually have been a type of burrowing sea anemone with a barrel-shaped body.

Julius Csotonyi

Share this:

- Share via email (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share to Google Classroom (Opens in new window) Google Classroom

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

By Meghan Rosen

What do you get when you flip a blobby “jellyfish” fossil upside down? You might just spy an ancient anemone.

Scientists think they’ve just come across a case of mistaken identity. Once thought to be fossils of ancient jellyfish, they now appear to likely show a burrowing sea anemone. Scientists shared their surprise discovery March 8 in Papers in Palaeontology.

Jellyfish and anemones are related. Jellyfish float freely in the water with tentacles that hang down from a bell-shaped body. Anemones usually live on the ocean floor or other surfaces. Their tentacles stick up into the water to catch prey.

Viewed one way, fossils of Essexella asherae appear to have a smooth bell shape with tentacle-like ridges hanging from it. This way, it looks like a jellyfish. And for more than 50 years, that’s how many scientists described this critter.

But something about that identity seemed fishy to Roy Plotnick. “It’s always kind of bothered me,” says this paleontologist. He works at the University of Illinois Chicago. One feature of this fossil had been described as a curtain that hung around the jellies’ tentacles. The problem: “No jellyfish has that,” he says. “How would it swim?”

One day, Plotnick was looking at some of these fossils at Chicago’s Field Museum. Suddenly, something clicked in his mind. What if the bell belonged on the bottom, not the top?

So he rotated the fossils half-way round. Suddenly, they looked kind of like a stretched-out pineapple with a stumpy crown. It now resembled some modern anemones.

“It was one of those aha moments,” he says.

Viewpoint matters

The “jellyfish” bell might be the anemone’s lower body, he decided. And the parts that looked like tentacles? Perhaps those were the anemone’s upper section — a tough, textured barrel that sticks up from the seafloor.

Plotnick and his team examined thousands more of these fossilized animals. This turned up even more anemone-like clues.

Bands running through the fossils match the shape of muscles in some modern anemones. And pointy protrusions on some fossils look like an anemone’s drawn-in tentacles.

“It’s totally possible that these are anemones,” says Estefanía Rodríguez. Though not involved with the work, she studies anemones at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. The shape of the fossils. The way they resemble modern-day anemones. These all line up, she says. Still, she adds, it’s not easy to know for sure what animal made them.

Animals like Essexella are some of the most difficult fossils to identify, notes Thomas Clements. “Jellyfish and anemones are like bags of water. There’s hardly any tissue to them,” he says. So when they die, there’s little to fossilize. Clements works at Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg in Germany. A paleontologist, he was not part of the new study.

Just looking at the fossil blobs, it’s hard to be sure they were anemones, he says. But where they were found does support the idea that they were. Long ago, Essexella lived near what’s now Mazon Creek in Illinois. Clements has spent several field seasons there. Back 310 million years ago, he says, this area was near a shoreline. Nearby rivers would have dumped sediment into the environment. And that’s just the type of place that ancient burrowing anemones might have once called home.