Magnetic fields melt and re-form new shape-shifting devices

Gallium plus magnetism equals something straight out of science fiction

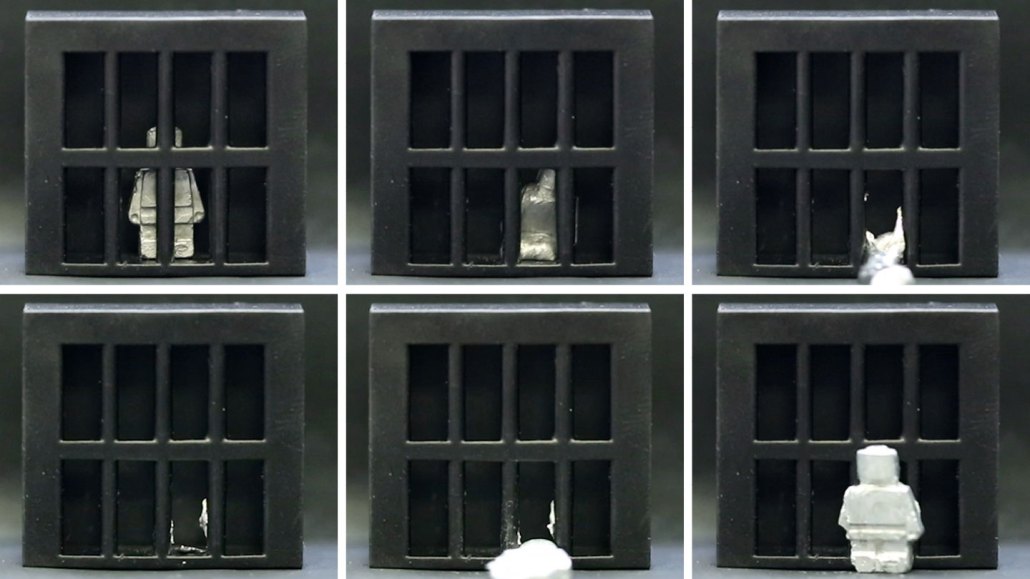

This Lego-like figurine escaped a toy prison thanks to its special material: a mix of gallium and magnetic particles. The new material liquefies when exposed to a changing magnetic field and moves under the guidance of a permanent magnet.

Q. Wang et al/Matter 2023 (CC BY-SA)

Share this:

- Share via email (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share to Google Classroom (Opens in new window) Google Classroom

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

Shape-shifting liquid-metal robots might not be limited to science fiction anymore.

Robots that melt and reform have appeared in movies like Terminator 2. Now, researchers have created a material that can similarly switch from solid to liquid and back. They used it to build mini machines. These can squeeze into tight spaces and do tasks, such as soldering a circuit board. Someday, the new material could give flexible robots the ability to shimmy through narrow passages.

Researchers described the work January 25 in Matter.

The inspiration to build shape-shifting devices came from nature. Sea cucumbers, for instance, “can very rapidly and reversibly change their stiffness,” notes Carmel Majidi. “The challenge for us as engineers is to mimic that in the soft materials.” A mechanical engineer, Majidi works at Carnegie Mellon University. That’s in Pittsburgh, Pa.

To make shape-shifting devices, his team turned to gallium. This metal melts at about 30° Celsius (86° Fahrenheit). Rather than using a heater, the researchers melted the material with a rapidly changing magnetic field. The changing field generates electricity within the gallium. This causes it to warm and melt. The material becomes solid again when it cools back to room temperature.

Magnetic particles are sprinkled throughout the gallium. As a result, a permanent magnet can be used to drag the material around. When the material is solid, a magnet can move it about 1.5 meters (5 feet) per second. The magnetized gallium can also carry about 10,000 times its weight.

External magnets can manipulate the material in its liquid form, too. They can make it stretch, split and merge. But controlling the fluid’s movement isn’t easy. Those magnetic particles in melted gallium can swivel around. So, their magnetic poles get all jumbled up. That makes the particles move in different directions in response to a magnet.

Majidi and his colleagues used their material to construct tiny machines. One toy person escaped a jail cell by melting between the bars and becoming solid on the other side. The toy regained its original shape using a mold placed just outside the bars.

Another machine removed a small ball from a model human stomach. It did this by melting slightly to wrap itself around the ball before slipping out of the organ.

On its own, gallium would melt inside the human body, which runs at about 37 °C (98.6 °F). But adding other metals to the gallium, such as bismuth and tin, could raise the material’s melting point. That might allow shape-shifting devices to be used in medicine.

Amir Jafari is a biomedical engineer at the University of North Texas in Denton. He was not involved in the work. The new shape-shifting material is a big step forward, he says. But challenges remain for using it in medicine. For one thing, he says, it might be hard to precisely direct the devices inside the body using magnets that stay outside the body.