This space physicist uses radios to study eclipses

Nathaniel Frissell works with amateur radio operators to learn more about our atmosphere

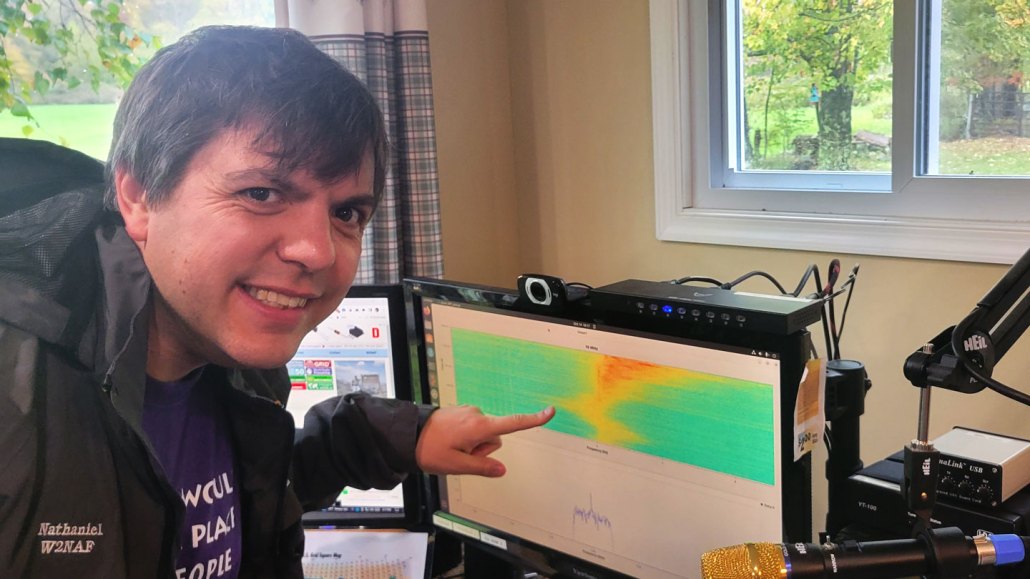

Space physicist Nathaniel Frissell works with ham radio operators to study how eclipses affect a layer of the atmosphere called the ionosphere. Here he sits in front of his personal ham radio setup during last year’s annular eclipse.

Ann Marie Rogalcheck-Frissell

Share this:

- Share via email (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share to Google Classroom (Opens in new window) Google Classroom

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

Next month, Nathaniel Frissell will lead a worldwide effort to collect data during the solar eclipse. Frissell is a space physicist at the University of Scranton in Pennsylvania. But he won’t be investigating the eclipse with a telescope or spectrometer. He’ll be teaming up with amateur radio, or ham radio, operators to collect data through the organization Ham Radio Science Citizen Investigation, or HamSCI, to study the ionosphere.

Ham radio operators are located around the world. They might use their radios to talk to people in their town or in another country. Some help during emergencies. Others participate in science. During the solar eclipse, they’ll help Frissell study how the eclipse affects a layer of the atmosphere called the ionosphere, which starts about 80 kilometers (50 miles) above the ground. The electrically charged particles in this layer reflect radio waves. During a solar eclipse, less sunlight reaches the ionosphere. This can lead to fewer electrically charged particles and, in turn, disrupt radio signals.

Frissell has been lucky enough to turn his childhood hobby, amateur radio, into a career. In this interview, he shares his experience and advice with Science News Explores. (This interview has been edited for content and readability.)

Do you have a science question? We can help!

Submit your question here, and we might answer it an upcoming issue of Science News Explores

What inspired you to pursue your career?

In middle school, I went on a Boy Scout trip where I met a ham radio operator. He was talking to people all over the world using just a radio setup and a wire. I became fascinated with radios and how the signals get from one place to another. I was also interested in showing others how it works. I kept following that passion until I got my Ph.D. in electrical engineering.

In graduate school, I realized that the radio signals that amateur radio operators use are greatly affected by space weather, which describes how the sun affects the Earth. I felt that there should be a more formal way of getting the amateur radio community and the professional science community to work together. The amateur radio community has this real spirit for investigation, research and engineering. So I created the Ham Radio Science Citizen Investigation, or HamSCI.

How did you get to where you are today?

I had majored in physics as an undergrad at Montclair State in New Jersey and went to Virginia Tech, in Blacksburg, for my Ph.D. in electrical engineering. Virginia Tech had a ham radio club and was a fairly outdoorsy place, things I wanted. I started looking for ways to join the ham radio community and the professional community together. I discovered a ham radio network called the Reverse Beacon Network [RBN]. They use automatic receivers located around the world that are constantly listening to Morse code signals. I downloaded their data showing when solar flares happen. I showed how clearly you could see the radio blackout during solar flares. I published that work in the journal Space Weather. It really opened the door for leading citizen science projects with ham radio data.

After that, I met some other people at Virginia Tech who wanted to study the ionosphere during the 2017 solar eclipse. These eclipses basically serve as controlled experiments that let us study the upper atmosphere in the absence of the sun’s light. I suggested that we could do that with ham radio data, too. It was during that project when we developed HamSCI. We created a website and a group that lets professional researchers connect with the amateur radio community. We managed to get ham radio operators from all across the nation on their radio during the 2017 eclipse. That data was analyzed and published in Geophysical Research Letters.

How do you get your best ideas?

I’m very collaborative and good at connecting people with others who share interests. For instance, a couple months ago, I was contacted by the Lackawanna Blind Association here in Scranton. They wanted someone to talk to them about ham radio. Having known some blind ham radio operators, I was eager to do it. Later, I was at a NASA science conference. There, I found they had copies of a book called Getting a Feel for Eclipses. It’s a Braille book that explains how solar eclipses work. It had these embossed infographics of solar eclipses that were absolutely gorgeous. When I asked for a copy, they gave me a whole stack.

I’m going to bring them back to the Lackawanna Blind Association. I’d like to put together a program or talk on eclipses. We have all this data from the annular solar eclipse that we just took this past October. We can convert that data into audio so that people can hear it.

What would you say is one of your biggest successes?

Creating the HamSCI group. Ham radio operators have been contributing to space physics and radio science for about a century. But I’ve been able to lead a resurgence of this. I’ve connected people who are doing this work from all around the world. Creating this community is a really big thing.

What was one of your biggest failures and how did you get past that?

I think I come across lots of little failures every day. It’s an important message to have people not get discouraged. My projects don’t always work out the way I planned. But I’ll learn something different from that work instead. You have to keep readjusting to keep things moving in the right direction. When you come across challenges, try to just stay calm and don’t give up. Ask yourself how you can do things differently. Or take what’s really good here and move it forward.

What advice do you wish you’d been given when you were younger?

I often hear about people who get discouraged when life isn’t working out the way they had hoped. We are often told to follow our dreams. I feel like I’m a very fortunate person since I’ve been able to turn my hobby into a career. Not everyone is in that position, though. Making this work, though, is not necessarily as straightforward or easy as it sounds.

The one thing I’ve been able to do is to keep a positive attitude. I’ve really been able to value my positive impact on others. At the end of the day, that’s the most important thing to me. I think the advice of following your dreams is still really good. But it’s also about coming up with creative ways to reach them. Sometimes you need to really persevere.