Here’s how rainwater might one day power some of your lights

In tests, the electricity that droplets made was small, but could keep a dozen LEDs lit

Water carries a lot of built-in energy. Researchers have now found a way to harness some of that energy from rain and other sources as a clean source of electric power.

Willowpix/Getty Images

Share this:

- Share via email (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share to Google Classroom (Opens in new window) Google Classroom

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

By Jude Coleman and Larissa G. Capella

They say April showers bring May flowers. But here’s another upside to rain any time of year: It could power some of your lights with clean, green energy.

Hydropower typically harnesses the strong flow of a big stream of water to create electricity by some mechanical means — such as the spinning of big turbines. A new type instead harnesses tiny bursts of energy sparked when rain runs down a narrow tube.

“There is a lot of energy in rain,” says Siowling Soh. An engineer, he works at the National University of Singapore. His team is developing the new tech. “If we can tap into this vast [rain] energy,” he says, “we can move toward a more sustainable society.”

A water molecule, or H2O, is made of two hydrogen atoms bonded to an oxygen atom. Some experiments had shown the electric charges in a water molecule can become spatially separated as water flows through an electrically conducting tube.

As those drops move, negatively charged hydroxide molecules (OH–) leave the droplet. These can latch onto the tube’s inner surface. This will leave an excess of positively charged hydrogen ions (H+) in the water.

As droplets dribble out of the tube and into a cup, the extra charge builds up in the accumulated water. That charge can create an electric current.

In early tests by others, the share of water molecules affected this way had been truly tiny. So the energy they produced was small, too. Indeed, it was far less than would be needed to continuously pump water through that tube.

Soh sought a way around that problem. His team’s new solution: Mix air in with that water.

Here’s how it works

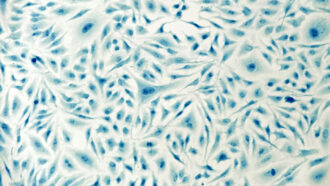

Instead of sending a continuous flow of water down a tube, they drip rain-like water droplets into it. To maximize the separation of electric charges, they keep the tube small. That way, a larger share of the water contacts the tube’s walls. (The tube’s 2-millimeter width is about as wide as a rice grain.)

Tiny air pockets develop between the water driblets as they slide down that tube. This process creates higher rates of charge separation than do continuous flows, Soh reports. In fact, it releases roughly 100,000 times as much energy!

The separated positive and negative electric charges create a voltage between the ions. It’s much the same idea as the charge separation that occurs when you shuffle across a rug wearing socks (and then risk getting a small shock when you touch metal).

After traveling the length of the tube, each charged droplet falls into a stainless-steel cup. Wires connected to the tube and cup allow those built-up electric charges to create an electric current, which can power some device.

Power wash

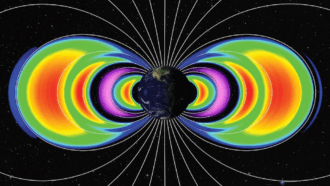

Water moving down a tube can support an electric current. But based on the tube’s width (compared to water flow) — and whether air pockets mix in — that water’s flow can exhibit any of five patterns. Each is illustrated and then photographed here. They appear in order from most power generated (with air-pockets, left) to least (right).

Soh’s group ran 20-second-long tests of its system. Droplet flows through four tubes — each 32 centimeters (12.6 inches) long — made enough electricity each time to continuously power 12 LED lights.

“We think [this new tech] will be helpful in rainy places, including tropical countries like Singapore,” Soh says. It could be scaled up, he adds — perhaps by installing rain-catching tubes on roofs. A system like this might also be set up next to sources that create sprays of water, such as waterfalls.

And this tech can do more than power little lights, Soh’s team reports. For instance, they showed how that electricity can be used to drive chemical reactions. Indeed, the engineers say, they’ve shown for “the first time that harvesting the constantly separated [electric] charge at the solid–liquid interface is … a practically useful source of electricity.”

Soh’s group shared details of all this in the May 28 issue of ACS Central Science.

Do you have a science question? We can help!

Submit your question here, and we might answer it an upcoming issue of Science News Explores

New twist on an older idea

This basic concept is not new, notes David Ma. This engineer at Texas A&M University in College Station worked on a somewhat related system seven years ago.

“Our team focused on one droplet at a time moving across a surface,” recalls Ma. “This new approach is clever because it generated more droplets in a simple way.”

Himanshu Mishra also finds this new setup “an interesting way to learn [how electric charges behave].” It shows what happens when water touches the inside of the tube — tiny charges build up in a way that can generate electricity. A physicist, Mishra works at King Abdullah University in Thuwal, Saudi Arabia.

The team behind the new tech says it can make up to 100 watts of power for each square meter of surface area collecting water. That’s a big jump compared to older methods, says Ma.

But there’s also a catch, he adds.

The device only works well when it’s connected to something with very high electrical resistance. That’s close to an “open circuit,” he explains — “where barely any current flows.” For that reason, he says, it can power only small things, such as tiny LED lights.

“It won’t work for regular light bulbs,” Ma says, “because those need more current.”

Mishra calls it “interesting science.” But “it won’t solve our global energy problems,” he notes. “We can’t expect it to replace fossil fuels.”

It does suggest a clean new way to tap electricity from the environment, though. Even if it may only serve as a bit player for now.