birds: Warm-blooded dinosaurs with wings that first showed up at least 150 million years ago. Birds are jacketed in feathers and produce young from the eggs they deposit in some sort of nest. Most birds fly, but throughout history there have been the occasional species that don’t.

brine: Water that is salty, often far saltier than seawater.

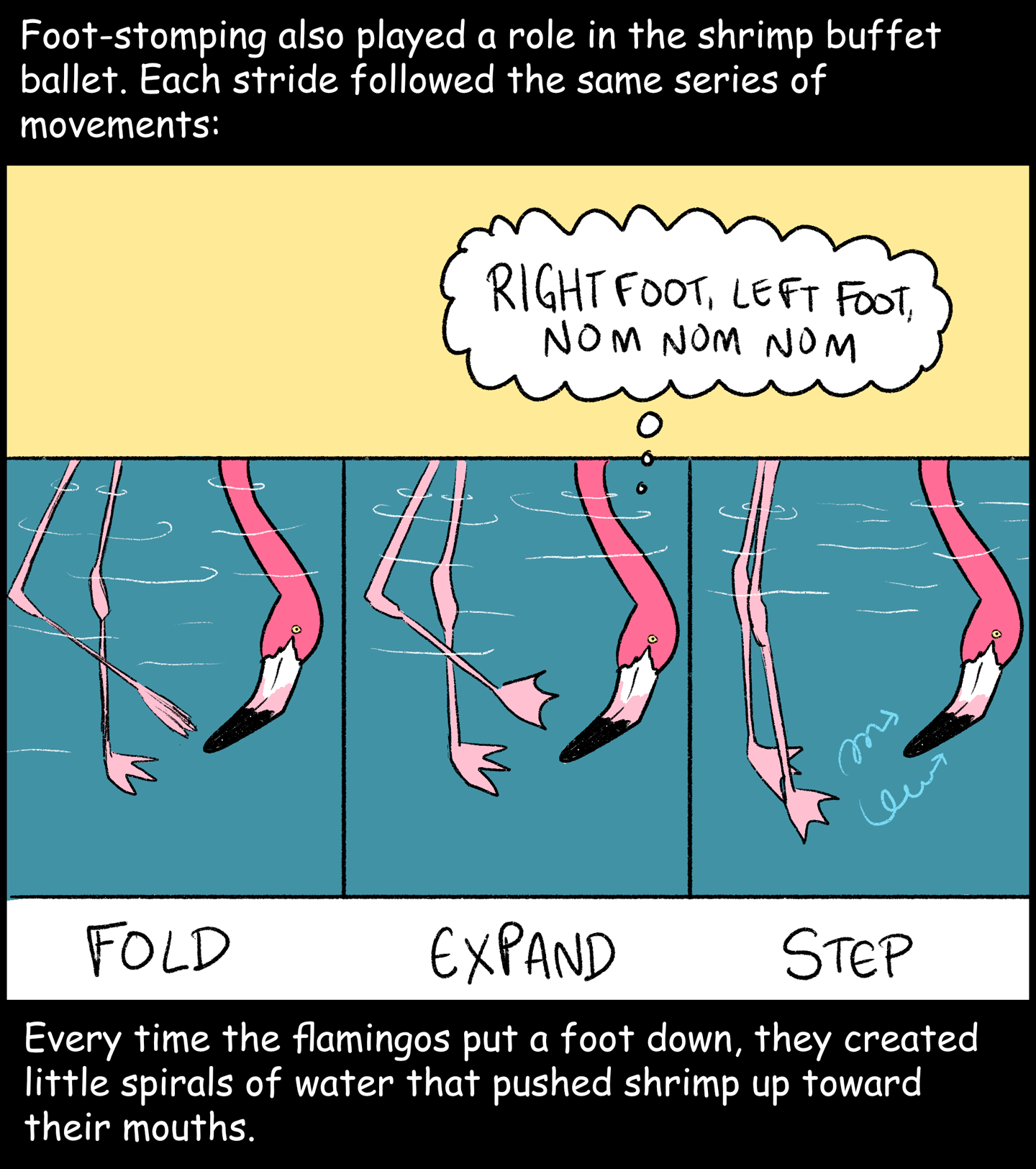

choreograph: (n. choreography) The process of planning or designing each step in a complicated performance (be it dance, ice skating or the movements across the stage in some play). Or it can be setting the controls to set the role of each participant in some precision operation (such as battlefield plan of attack or marching band’s half-time display). The person who does this planning is known as a choreographer.

family: A taxonomic group consisting of at least one genus of organisms.

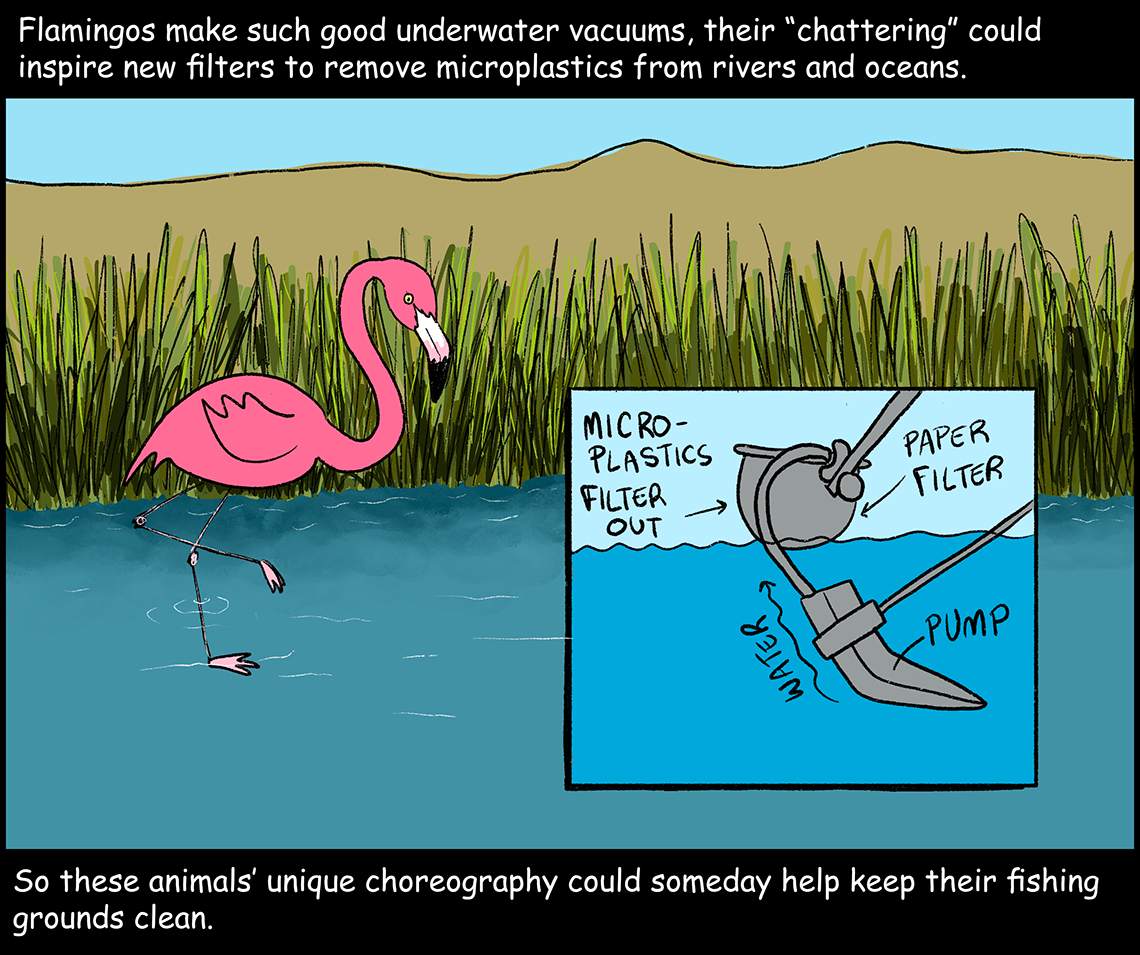

filter: (n.) Something that allows some materials to pass through but not others, based on their size or some other feature. (v.) The process of screening some things out on the basis of traits such as size, density, electric charge. (in physics) A screen, plate or layer of a substance that absorbs light or other radiation or selectively prevents the transmission of some of its components.

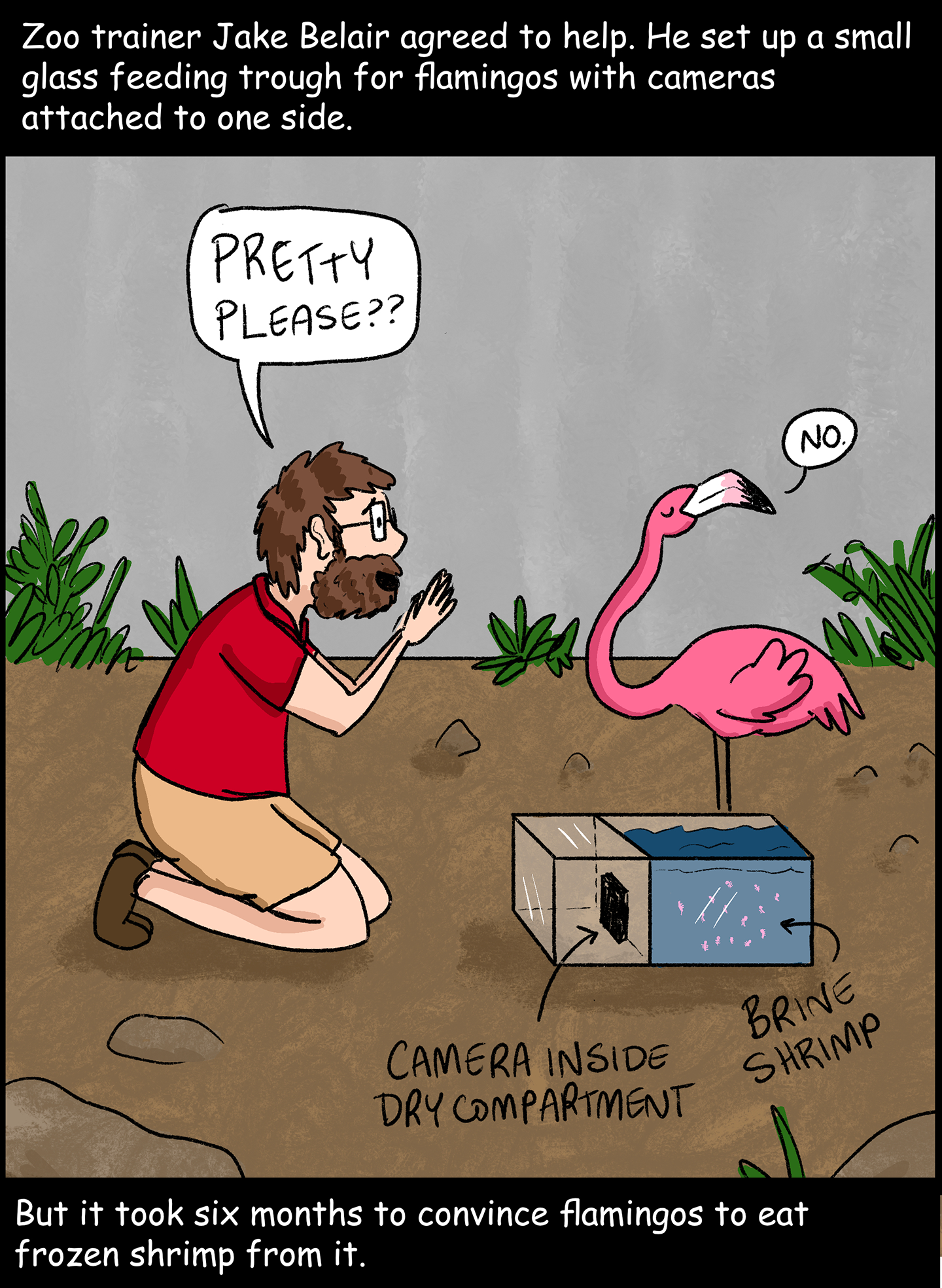

glass: A hard, brittle substance made from silica, a mineral found in sand. Glass usually is transparent and fairly inert (chemically nonreactive). Aquatic organisms called diatoms build their shells of it.

microplastic: A small piece of plastic, 5 millimeters (0.2 inch) or smaller in size. Microplastics may have been produced at that small size, or their size may be the result of the breakdown of water bottles, plastic bags or other things that started out larger.

salt: A compound made by combining an acid with a base (in a reaction that also creates water). The ocean contains many different salts — collectively called “sea salt.” Common table salt is a made of sodium and chlorine.

swarm: A large number of animals that have amassed and now move together. People sometimes use the term to refer to huge numbers of honeybees leaving a hive.

trough: A channel, gully or depression in the land that can collect liquids. Or a container with a U-shaped bottom from which animals may feed or drink. (in physics) the bottom or low point in a wave.

unique: Something that is unlike anything else; the only one of its kind.

vacuum: Space with little or no matter in it. Laboratories or manufacturing plants may use vacuum equipment to pump out air, creating an area known as a vacuum chamber.

vortex: (plural: vortices) A swirling whirlpool of some liquid or gas. Tornadoes are vortices, and so are the tornado-like swirls inside a glass of tea that’s been stirred with a spoon. Smoke rings are donut-shaped vortices.