Good at reading? That’s no sign girls won’t also cut it in STEM

Girls are as good as boys at math but fewer seek careers in STEM. This may be why

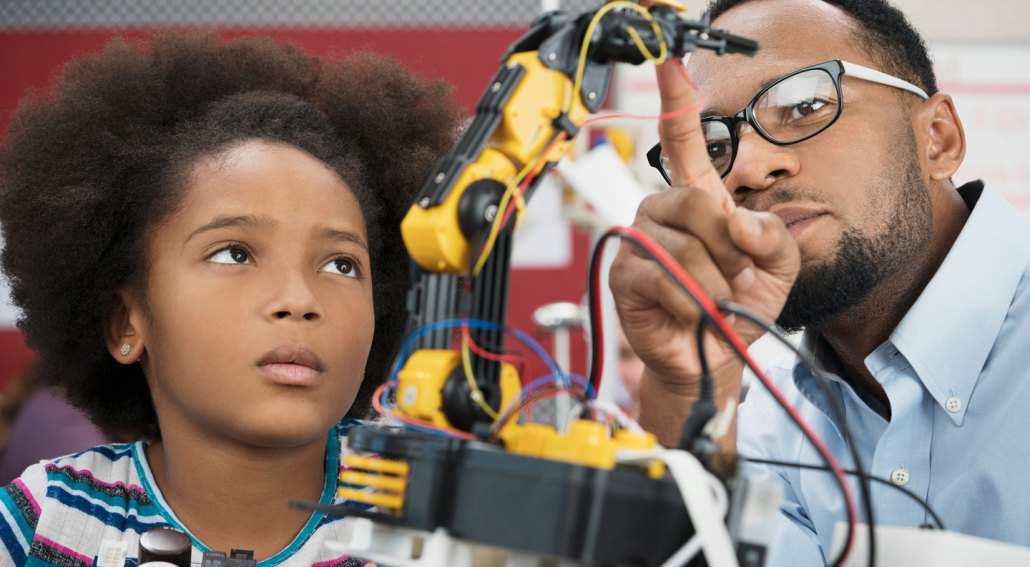

U.S. girls tend to be better than boys in English. It now appears many people mistakenly interpret this to mean girls might not be cut out for STEM careers. In fact, when encouraged, even young girls are just as good at STEM subjects as boys are.

Ariel Skelley/DigitalVision/Getty Images Plus

Share this:

- Share via email (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share to Google Classroom (Opens in new window) Google Classroom

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

What do you picture when you think of a scientist — or an engineer, economist or mathematician? Many see a man. In fact, there are three men for every woman working in science, technology, engineering or math — the STEM fields. A new study thinks it’s found one unexpected reason why.

Girls, its data show, may steer clear of STEM because they want to stick with subjects that they know they’re especially good at: reading and writing. What’s more, parents may be playing a role in shaping this view that girls would do better here than in jobs that rely on math, science or tech. In late March, researchers shared their findings in the American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings.

For centuries, boys often got a better education than girls. But in most parts of the world that’s no longer true. A new report on global education finds that in most countries, girls and boys receive equal educational opportunities. In these nations, girls are also just as good at math and science as boys are. Reading is where girls tend to excel at a young age.

Anya Samek is an economics researcher at the University of California San Diego. Economics uses a lot of math. Samek found that most of her coworkers were men. She wanted to know why more girls don’t go into STEM jobs. So she teamed up with researchers from across the United States to find out.

Back in 2010, Samek started a long-term study. She was part of a team that created a preschool in Chicago, Ill. They recruited families with young children each year for four years. These were families who would not otherwise have sent their kids to preschool. The team tested the kids’ thinking and reasoning skills, memory and attention. They also asked the parents a long string of questions. Some were about their children. Others surveyed their own beliefs about education.

The researchers then randomly assigned the kids to one of three groups. Group one attended the preschool. There they learned about letters, reading, counting and how to play nice with other kids. Group two didn’t attend the preschool. Twice a month, their parents attended an “academy” to learn how to teach their kids the same things the preschool group was learning. The third group served as a control, meaning it didn’t receive either form of instruction.

Girls stick with what they’re good at

Samek’s team followed the kids over the years. When these children were 8 to 14 years old, the team compared their scores on standardized tests. Kids who went to preschool or whose parents attended the parent academy did better in reading — but not math. Girls were stronger readers than boys as early as third grade. And that gap grew as the students got older. Throughout, there were no differences in the math scores of boys and girls.

Parents spent more time teaching girls than boys when they were young, the study found. “We don’t know why,” Samek says. It could be due to the parents’ belief that their kids would one day go to college, she says. Or, she offered, “maybe it’s harder to teach to boys, because they are less likely to sit still.” Survey data from the parents showed some support for both reasons.

Does the time parents spend with their young kids affect standardized test scores later on? “We do see a correlation,” Samek says. But it’s stronger for English than for math. She stressed that it’s only a correlation. That means the two are related. But there are not enough data to show that early education caused those higher test scores later in life.

Why do girls do so well in reading and language skills? Samek isn’t sure. But she thinks it could have to do with how parents are told to teach their children. “We really push this idea we should be reading to kids,” she says. “We are less likely to tell parents, you [also] need to be counting with your kids.”

Based on their findings, the team now suspects this may explain why girls choose more language-based classes — and later, jobs. It’s not because they’re bad at math or science. It appears to be because they excel at English and then stick with what they know they’re really good at.

That’s an important finding. “Girls are not behind,” Samek notes. But sticking with the thing you’re good at isn’t necessarily the best choice. She recommends instead that you “spend more time picking the [field] that is going to give you the best career.”

English skills will be useful no matter what career students choose. STEM jobs require strong communication skills, Samek notes. And if girls excel at communication, she suspects they may find they’ll have an advantage in STEM careers, too.

Jessica Esquivel agrees. She’s a particle physicist at the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory in Batavia, Ill. She was not involved with the new study, but she does work to increase diversity and representation in STEM. “A strong understanding of language is an integral part of being a scientist,” she says. “One of our main duties is to be able to communicate our research to others.”

Increasing awareness of the diversity of both STEM fields and the people who work in them is essential, she says. And strong communication, she feels, is key to closing the gender gap in STEM fields.