The secret life of fruit flies

Scientists find that the most attractive scent for a fruit fly is no scent at all

Share this:

- Share via email (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share to Google Classroom (Opens in new window) Google Classroom

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

|

|

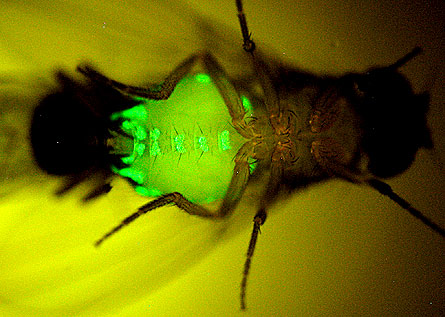

The cells in Drosophila melanogaster that produce pheromones are located in the abdomen. Here, the cells are marked by a green fluorescent protein.

|

| Jean-Christophe Billeter |

View a video of fruit flies displaying unusual courtship behavior.

Fruit flies linger over a bowl of rotting fruit. To untrained eyes, the flies may look like a swarming nuisance, but scientists have found that flies’ swoops and buzzes are ways to send signals through the crowd. Another, less obvious way these insects communicate is through chemical signals called pheromones. (It’s easy to think of these chemical signals as being similar to smells.)

Scientists have long known that pheromones may play an important role in reproduction — certain pheromones may attract a potential mate, for example. But in a surprising new study, scientists found that male fruit flies are particularly attracted to other flies — male and female — that don’t put out any pheromones at all.

The researchers also found that fruit flies without pheromones are attractive to males of other species. This research suggests that pheromones may be even more complicated — and important — than scientists thought. Besides telling other insects to come a little closer, pheromones may also be used to say, “Back off!” That message is important for keeping up barriers between species.

There are many different types of fruit flies, no matter how similar they all look as they swarm over a rotting tomato. Scientists have wondered how fruit flies can tell each other apart. Appearance may play a role. So may sound — the mating song of each different kind of fruit fly is different, for example.

Scientists suspect pheromones may also help fruit flies find potential mates of the same species — but there are 30 or more pheromones to choose from. In the new study, which was led by Joel Levine, the scientists wanted to figure out what messages the different flavors of pheromone were each sending. Levine is a neurogeneticist at the University of Toronto at Mississauga. (Neurogenetics is the study of how genes affect the development and function of the brain and the nervous system.)

His team genetically altered fruit flies so that the flies no longer made pheromones. Then the researchers watched the mating behavior of the insects, and observed that males went after the flies that didn’t have pheromones.

“Males are only after one thing. They want to mate,” Levine told Science News. Females, on the other hand, preferred males with pheromones to the males without. “She will not go for the guy who has no odors,” Levine said. He and his team also used the scentless flies as a starting point for other experiments. They were able to identify one particular pheromone, for example, that kept flies of different species from breeding.

These chemical signals help flies tell males from females, and help tell members of different species from each other. The new research suggests that pheromones may be more important than sight or sound in that crowd of flies hovering over the fruit bowl. “We expected the chemicals would play a role,” Levin said, but “we had no reason to think that the effects we saw would be so strong.”

Strange Attraction from Science News on Vimeo.

In the absence of pheromones, flies engage in unnatural courtship behavior. In this movie, two males attempt copulation with each other’s heads.

Credit: Jean-Christophe Billeter et al, Nature 2009

Going Deeper: