See what these animal mummies are keeping under wraps

A new method of 3-D scanning reveals life and death details of a snake, a bird and a cat

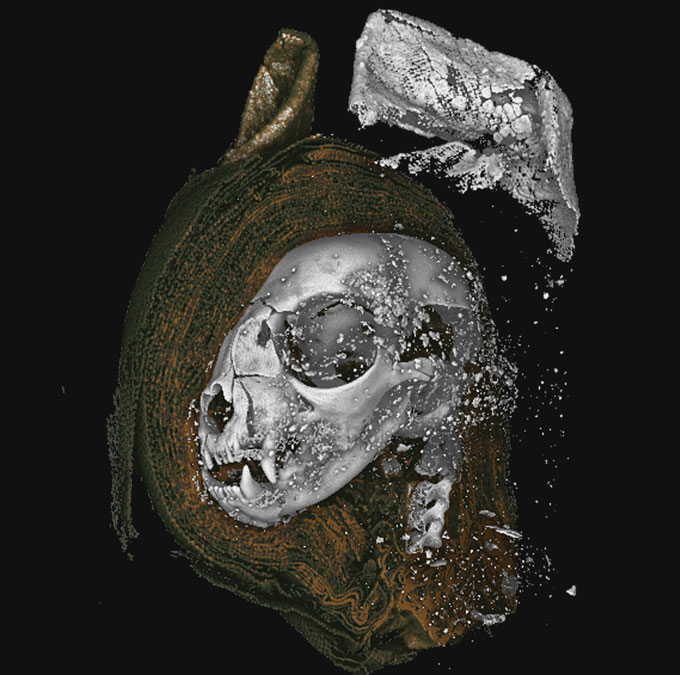

Three-dimensional scans of animal mummies reveal their identities and other secrets. The mummies are likely at least 2,000 years old. They include a snake (left), bird (top right) and cat (bottom right).

Swansea University

Share this:

- Share via email (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share to Google Classroom (Opens in new window) Google Classroom

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

Ancient Egyptians didn’t just mummify people, they also preserved many animals. Some of these mummies look like little more than bundles of cloth. Now high-tech X-rays have unveiled the mysterious life histories of three of these mummies — a cat, a bird and a snake.

All three belong to the Museum of Egyptian Antiquities at Swansea University in Wales. Two-dimensional X-rays of each specimen existed. But there was little information beyond generic animal labels. Richard Johnston wanted to know more. He’s an engineer at Swansea University. So he and his colleagues used a microCT scanner to see what lay beneath the wraps of these animal mummies.

A microCT scanner uses X-rays to see inside an object. It’s similar to the CT scanner that is found in a hospital. But it offers much more detailed images.

The bone scans provided such detail that researchers could tentatively identify the cat as a domestic kitten (Felis catus). The bird most closely resembles a Eurasian kestrel (Falco tinnunculus). And the snake was likely an Egyptian cobra (Naja haje). The team described all three August 20 in Scientific Reports.

Cause of death was clear in two cases: The kitten appeared to have been strangled, and the snake had its spine broken. The snake also suffered kidney damage. This may have been due to water deprivation near the end of its life.

The team focused on sections of each animal rather than scanning the whole mummy at once. This allowed the researchers to get rare detail. They could then create models of the mummified remains. Those models could be 3-D printed and investigated through virtual reality. “With VR, I can effectively make the cat skull as big as my house and wander around it,” Johnston says. That’s how the team found the kitten’s unerupted molars, a clue that this cat was less than five months old.

Using microCT scans for mummies is novel and definitely has potential, says Lidija McKnight. She’s an archaeologist at the University of Manchester in England. She did not take part in the study. She says that “these advanced techniques are extremely powerful tools to improve our understanding of this ancient practice.”

Ancient Egyptians produced millions of animal mummies. Some were pets. Some were food for the afterlife. But most served as offerings to Egyptian gods. Farms raised some animals for mummification. These offerings were sold to worshippers outside temples. The three mummies in this study probably fell into that last category.

Scans of the snake hint at an Egyptian ritual. This mummy had structures about the size of a grain of rice in its open mouth. This may have been natron, the mineral used by ancient Egyptians to slow decomposition. Ancient embalmers often opened the mouths and eyes of mummies. This was so that in the afterlife, the dead could see and communicate with the living. Until now, this type of procedure had mostly been seen in human mummies. Snakes, it appears, may have also whispered beyond the grave, serving as a messenger between the gods and a worshipper.