Gold’s Glittery Rewards

Gold has properties that make it valuable not only for jewelry but also for electronics and other uses.

Share this:

- Share via email (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share to Google Classroom (Opens in new window) Google Classroom

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

By Sarah Webb

We all recognize gold, from the yellow sparkle of a chain necklace to the shiny coating on a DVD player’s video and audio plugs.

|

|

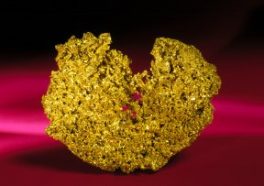

This delicate, crystallized gold specimen was found in Leadville, Colorado. |

| © Denis Finnin/AMNH |

Gold is a metal. It conducts electricity, and it can be shaped into sheets, long wires, or rings. Gold is an element—a substance made of one kind of atom. As an element, gold has its own square on the periodic table of chemical elements.

Gold also represents beauty and value, and it has done so for thousands of years. It’s part of our culture and history.

Why do we value gold so much? It has a distinctive color. No other metal is a shiny yellow. It’s also quite rare.

And this metal has other unique properties that help it keep its shine, as I learned on a recent trip to the new gold exhibit at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City.

Keeping its luster

The glitter of a gold nugget or flake immediately catches the eye. But gold’s shine, unlike that of metals such as iron, copper, or silver, is practically permanent.

For example, copper metal has a reddish color. But copper objects turn green when they react with oxygen in the air. This coating on a copper surface, called a patina, gives the Statue of Liberty her distinctive green color.

|

|

The Statue of Liberty has a greenish color because the copper metal from which it was made combined with oxygen in the air. |

| Photo by I. Peterson. |

In contrast, gold resists corrosion. It doesn’t react with chemicals in the air or elsewhere in the environment. So it doesn’t turn green as copper does, rust the way iron does, or tarnish the way silver does.

Shaping a nugget

Gold is also a soft metal that’s easy to shape. People have been working with it for thousands of years.

Gold artifacts are among the oldest [human-made objects] that we know, says Jim Webster. He helped create the gold exhibit at the American Museum of Natural History and studies earth and planetary sciences at the museum.

Unlike many other metals, gold can be found on the ground in its pure form. Instead of having to go through many steps to isolate a metal from rock, early people could have used gold nuggets that were just lying around.

“Literally, now or 6,000 years ago, one could have picked up [a nugget] and just started hammering on it,” says Webster. Ancient people shaped gold into jewelry, statues, coins, and other beautiful objects.

|

|

Jewelry made in the shape of animals, like these gold earrings, was popular more than 2,300 years ago in ancient Greece. |

| © Craig Chesek/AMNH |

The property that allows gold to be shaped easily is called malleability. Gold can be hammered into very thin sheets without breaking.

Experts can make a thin sheet measuring up to 100 square feet in area from just 1 ounce of gold, Webster says.

The museum’s gold exhibit features a small room whose walls and ceilings are covered with gold—a layer just 0.18 micron thick. That’s a tiny fraction of the width of a pencil point.

|

|

Sarah Webb stands in the gold room at the American Museum of Natural History. The walls and ceiling are coated with a layer of gold only 0.18 micron thick. |

| Photo by Anne Sasso. |

Because gold is so soft, jewelers and other users often combine it with other metals to make it stronger. The purity of gold is measured in karats, and pure gold is 24 karats. Jewelry in the United States is often 14 karats, or about 60 percent gold, combined with other metals, such as silver or copper.

Rare metal

Even though gold has many special properties, the main reason for its value is its rarity.

Researchers estimate that the total amount of gold ever mined would fit into 60 tractor trailers, Webster says. This might seem like a lot—until you compare it with iron. Iron mining and smelting companies produce six times that amount every year.

Because of its value, people have made coins out of gold, and banks store gold in the form of bars. Some people collect gold coins or trade gold in international markets. Its current value is more than $600 per ounce.

|

|

Banks and gold markets can use gold bars for transactions. This bar weighs about 27 pounds and is roughly 6 inches long, 3 inches wide, and 2 inches thick. At current prices, it’s worth more than a quarter of a million dollars. |

| © C. Chesek/AMNH, Courtesy of Johnson Matthey, Inc. |

Electronic gold

Most gold that’s mined today still goes into making jewelry. You also see it in Olympic medals and many other special awards, including the Oscar statuettes that honor movies.

But modern electronics and the journey into space have helped give gold an important place in the technology that we use every day.

Audio and video cables often have gold-coated plugs for two reasons. Gold conducts electricity better than all but two other metals, Webster says. And because gold doesn’t corrode, the surface on the plug stays clean.

For the same reasons, computer chips also often contain gold, as do a variety of other electronic components.

We’ve also launched gold into space.

|

|

A thin layer of gold covered the visor on the helmet of an astronaut on the moon. The gold layer is transparent but still keeps out the sun’s heat. |

| NASA |

Gold reflects heat better than any other metal. The visor on an astronaut’s helmet has an ultrathin layer of gold. The layer is thin enough to be transparent, so the astronaut can still see through it. But this thin layer reflects the sun’s heat away from the astronaut.

The museum’s gold exhibit includes a helmet from the Apollo 11 mission, when astronauts first landed on the moon in 1969.

Even after thousands of years, gold remains a precious metal—one that has long been prized for its glitter and is now more useful than ever.

Going Deeper:

News Detective: Searching for Gold