Here’s how to levitate something without magic

You can defy gravity using sound waves, magnetism or even electricity

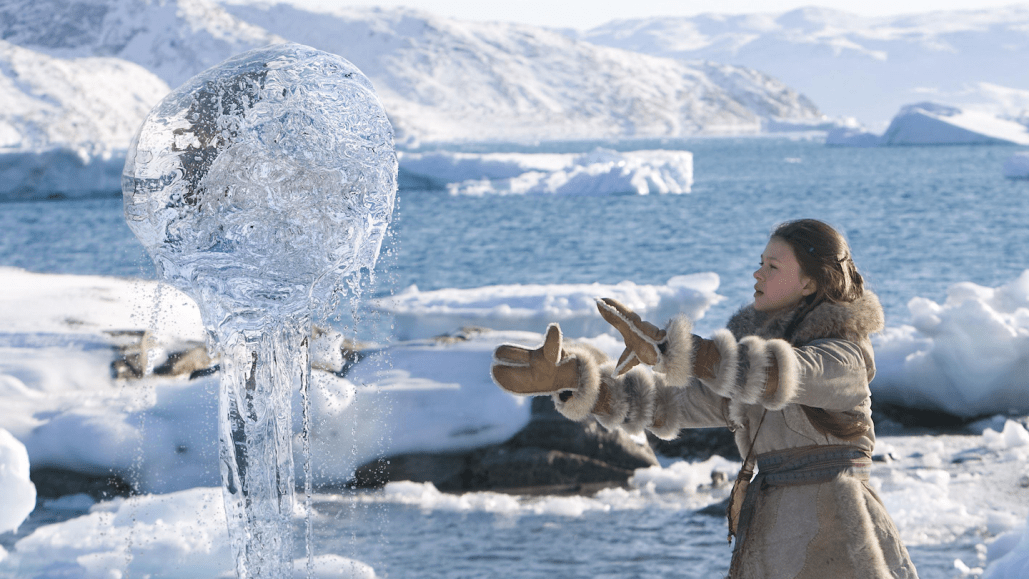

In Avatar: The Last Airbender, waterbenders can levitate liquid water and solid ice.

Entertainment Pictures/Alamy

Share this:

- Share via email (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share to Google Classroom (Opens in new window) Google Classroom

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

With a simple swish-and-flick of his wand, Ron Weasley yanks a troll’s club high above its head in Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone. Through graceful martial arts moves, element benders in TV’s Avatar series launch boulders and waves of water skyward. And a casual gesture is all Marvel hero Scarlet Witch needs to fling away her enemies.

Fictional heroes require magic or superpowers to lift objects without touching them. In the real world, you need physics. Sound, magnets and electricity, it turns out, can all create upward forces strong enough to cancel out the downward pull of gravity.

This ability to suspend objects in midair could transform lab experiments, transportation and more. Just don’t expect any real levitation technique to toss boulders or bad guys through the sky. At least, not without some outrageous — and dangerous — upgrades.

Let’s make some noise

If you’ve ever been to a concert where the music was so loud you felt it thumping in your chest, then you know firsthand how strong sound waves can be. Acoustic levitation devices use those vibrations to hold objects aloft.

“You can think of it as a very complicated surround-sound system,” says Luke Cox. An acoustic levitator may contain hundreds of little speakers. Those speakers typically blare noise at a frequency of 40 kilohertz. Humans can’t hear these sounds. “But if you look at the sound-pressure levels, it’s louder than a jet engine,” notes Cox. A mechanical engineer, he leads the company Impulsonics in Bristol, England.

Sound waves from an acoustic levitator create alternating spots in the air of high- and low-intensity noise. The force of sound pushes objects away from the loud areas. As a result, items placed in quiet areas will stay there, as if tucked into invisible pockets. Fine-tuning the noise blasted by each speaker can steer those pockets around.

Acoustic levitation can lift all types of materials, solid or liquid. But it can only support very small, lightweight things. Some of the heaviest stuff to ever surf sound waves were Styrofoam puffs (like those inside beanbag chairs).

Taller and wider objects need longer, lower-frequency sound waves to cradle them. Say you wanted to levitate a person — even someone curled into a ball. Cox estimates that would take at least 275-hertz waves, which are 1.25 meters (some 4 feet) long. Bass guitars play notes about that low. But the music from a bass-guitar levitator would also have to be devastatingly loud to lift someone off their feet.

“I’m probably going to need quite a few power plants” to run the device, Cox muses. “But maybe a big nuclear one could do it.”

On top of that, you’d need to shield anyone you levitated from the heat generated by that amount of power. Otherwise, your gnarly, nuclear-powered bass solo might literally melt their face off.

The might of magnets

Magnets, meanwhile, already safely lift objects much bigger than people off the ground.

Perhaps the most striking display of that brute strength is a maglev train. Magnets on its cars and tracks interact to create an upward force. It lets the train hover about 10 centimeters (4 inches) above the track. This allows the train to glide nearly friction-free and travel twice as fast as trains that roll on rails.

Magnetic levitation is not limited to magnetic metals, notes Eric Severson. He’s a mechanical engineer at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis. Diamagnetic materials also can accomplish this feat. Around a strong magnet, these materials can become weakly magnetized and start to repel the magnet. This repulsive force, though feeble, can win a fight against gravity.

Graphite, gold and many other substances are diamagnetic. Water, proteins and other molecules in living tissue are, too.

In 1997, two scientists famously used that fact to levitate a frog. They placed the creature inside a magnet made from two nested coils of wire. The field created by the device was 16 teslas. That’s about 10 times as strong as the magnets used to pick up cars in junkyards. And it was just enough to buoy the frog near the top of the inner coil of wire. That coil was 18 centimeters (7 inches) tall.

“You could theoretically make a person float,” Severson says. But you’d need one heck of a magnet. In 1998, one of the frog floaters estimated that you’d need a 40-tesla field created by a magnet running on 1 gigawatt of power. That’s roughly half the power produced by the Hoover Dam.

There’s another catch with magnetism: its short range. You have to be close to a magnet to feel its effects. So making something soar through the sky would likely require some other tech.

Sky’s the limit

Ballooning spiders already have high-flying levitation figured out. A flock of these critters once impressed and perplexed Charles Darwin by alighting on his ship some 100 kilometers (60 miles) out to sea.

“They spin out a very long thread of spider silk and then, in the process, charge themselves up electrically,” explains Igor Bargatin. This happens thanks to triboelectricity. “They lift off in the Earth’s electric field,” Bargatin says. “After that, they’re just carried by the wind.” Sometimes, airborne arachnids are swept kilometers (miles) into the atmosphere.

Bargatin is a physicist and engineer at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. When he first heard about ballooning spiders, he wanted to build something that would mimic their wingless flight. But he realized this spidey levitation won’t work for large objects.

Imagine trying to float a human. “The charge that they would need to accumulate is so large that you would start creating basically lightning all around you,” Bargatin says. That wouldn’t just be dangerous. It also would keep you from ever building up enough charge to take off.

All told, real-world levitation likely won’t ever measure up to the superpowers seen on screen. Still, it needn’t be flashy to be useful.

Acoustic levitation could handle tiny electronic components or lab samples without touching them. That would cut the risk of contaminating them. Severson uses magnetic levitation to make parts of motors float. That way they can spin faster without wearing down.

Scientists are still dreaming up new uses for levitation, too — ones that play to different techniques’ natural strengths and won’t risk frying anything during takeoff.