Global coral die-offs signal Earth’s first climate tipping point

It’s a dire warning, scientists say — and more such tipping points could be here soon

Near southern Thailand, a citizen scientist surveys bleached corals on June 14, 2024. Marine heat waves last year triggered the worst bleaching and coral die-off on record. It’s a point-of-no-return for coral reefs, researchers say, and shows Earth has passed its first climate tipping point.

LILLIAN SUWANRUMPHA/Contributor/Getty Images

Earth has entered a grim new climate reality.

The planet has officially passed its first climate tipping point. That’s a point where the effects of many smaller changes cause a sudden big change in Earth’s climate. It’s like that proverbial last straw that broke a camel’s back.

In this case, rising ocean heat has now pushed reefs around the world past their limit. Their corals are now dying off at a rate that’s worse than ever before seen. This reef damage threatens not only the world’s corals. It also puts at risk the livelihoods of those who depend on ocean resources — nearly 1 billion people.

Scientists share this dire conclusion in a new 374-page report. It was published on October 12 by a group of 160 researchers from 23 countries. The University of Exeter, in England, led the report.

All warm-water corals are virtually certain to pass a point of no return. That’s true even under the least-worrisome view of future ocean temperatures — one in which global warming does not exceed 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) above preindustrial times.

It’s “one of the most pressing ecological losses humanity confronts,” the report’s authors say in Global Tipping Points Report 2025.

And, they add, that loss of corals would be just the tip of the iceberg, so to speak.

“Since 2023, we’ve witnessed over a year of temperatures of more than 1.5 degrees C above the preindustrial average,” notes Steve Smith. A geographer at the University of Exeter, he studies tipping points and sustainable solutions. He spoke at a press event on October 7, just ahead of the report’s release.

“Overshooting the 1.5 degree C limit now looks pretty inevitable,” he says. In fact, he added, it could happen in just a few years, perhaps as early as 2030. “This puts the world in a danger zone,” he says. And, data his team reviewed suggest, the risk is rising “of more tipping points being crossed.”

Other tipping points loom

Tipping points are points of no return. Each nudges the world over a proverbial peak into a new type of climate — a new normal. That, in turn, triggers a host of changes.

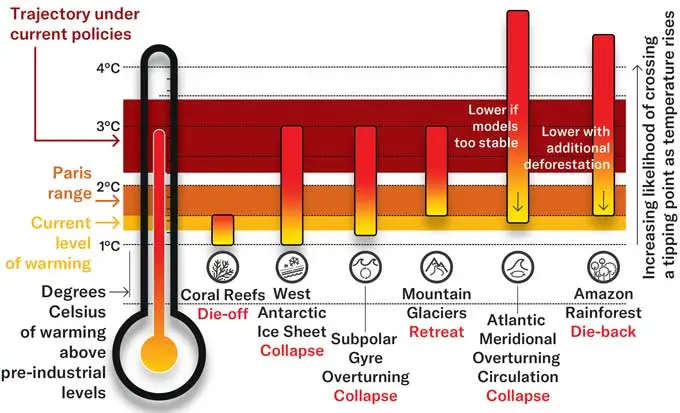

Depending how much warmer the next decades get, the world could witness a widespread dieback of the Amazon’s rainforest. The Greenland and West Antarctic ice sheets could collapse, leading to large and fast sea level rise. Most worrisome, a powerful ocean-current system could collapse. It’s called the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, or AMOC. If it shut down, the entire Northern Hemisphere could undergo a prolonged and dramatic cooling. This could also boost sea level along some Atlantic coastlines by up to 70 centimeters (about 30 inches).

It is now 10 years since a historic United Nations treaty. Nearly every nation signed this Paris Accord, agreeing to cut their greenhouse-gas emissions. Each signer pledged to keep its releases low enough to hold warming to well below 2 degrees C (3.6 degrees F) by the year 2100 (and preferably to no more than 1.5 degrees C). The hope was that this would hold off many of the worst impacts of climate change.

But in terms of emissions cuts, “we are seeing the backsliding of climate and environmental commitments,” says Tanya Steele. Both governments and companies have been to blame, she says. Steele runs the United Kingdom office of World Wildlife Fund (which hosted a press briefing for the new report).

The new report is the second tipping-point assessment put out by an international group of more than 200 researchers. They come from more than 25 institutions. The report’s release was timed to coincide with a meeting of ministers from nations. Many of the issues were on the agenda for this year’s annual United Nations Climate Change Conference, or UNCCC.

Do you have a science question? We can help!

Submit your question here, and we might answer it an upcoming issue of Science News Explores

The problem with tipping points

Last year, the world endured some 150 extreme-weather events. They included the worst-ever drought in the Amazon. This year’s UNCCC is being held near the heart of that rainforest. It will offer an chance to raise awareness about that looming tipping point, Smith said. Recent analyses suggest the Amazon rainforest “is at greater risk of widespread dieback than previously thought.”

Why? It’s threatened not only by warming. Large-scale cutting down of its trees — deforestation — is also underway. And having fewer trees lowers the threshold temp for a tipping point for Earth’s climate. Removing just more than one-fifth of the Amazon’s forest (22 percent) is enough to lower the tipping point to 1.5 degrees C, the report states. Right now, Amazon deforestation is close to that. It stands at about 17 percent.

But there is a glimmer of good news, Smith added. “On the plus side, we’ve also passed at least one major positive tipping point.” These tipping points, he explained, are steps that trigger a host of new, welcome changes.

Here’s one, he noted: “Since 2023, we’ve witnessed rapid progress in the uptake of clean technologies worldwide.” Electric vehicles are a big one, along with solar-cell tech. Meanwhile, battery prices for these technologies have dropped, too. And, added Smith, these changes “are starting to reinforce each other.”

Still, at this point, the challenge is not about just cutting emissions — or even pulling carbon out of the atmosphere, says report coauthor Manjana Milkoreit. She’s a political scientist at the University of Oslo in Norway. She studies what it will take to change human habits in ways that no longer warm Earth’s climate.

What’s needed is a wholesale shift in how governments think about dealing with climate change, Milkoreit and others write. The problem: Rules and government agreements — such as the Paris Accord — were never designed with tipping points in mind. They had been built on the idea that any changes would be gradual and linear, not abruptly shifting in many ways at once.

“What we’re arguing in the report,” Milkoreit says, “is that these tipping processes really present a new kind of threat.” They’re so big, she says, that it’s hard to wrap our heads around their scale.

Report calls for action

The report outlines several steps that decision-makers will need to take — soon. By waiting, more tipping points could be passed.

Quick action to cut releases of short-lived pollutants — such as methane and soot — would help. This could buy time until governments can address longer-lived ones. The world also needs to swiftly remove carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere on a large scale. Another priority: Cut the use of food and wood that encourage chopping down forests. Finally, the report emphasizes that governments need to quickly develop ways to cope with multiple climate impacts at once.

This won’t be easy, Milkoreit admits. “We’re bringing this big new message, saying, ‘What you have is not good enough.’” But dealing with the climate will not get easier in the future, only harder. She says researchers and the news media “struggle with selling the terrible news.” Even decision-makers don’t want to hear this message, she admits.

But it’s important not to look away, she and the report’s other authors say. They hope their data, charts and assessments will prompt us to consider what we can do now to help. It might be making different choices in what you buy, such as looking for used or recycled goods. It might also be as simple, Milkoreit says, as helping get out the message to more people — including friends or family — that the time to act is now.