Troubles with Hubble

Just before a planned repair mission, the space telescope went quiet

Share this:

- Share via email (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share to Google Classroom (Opens in new window) Google Classroom

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

By Susan Gaidos

If your family car breaks down on the road, a roadside assistance crew will be sent immediately to make repairs. But how do you tackle emergency repairs on an orbiting space telescope hundreds of miles from Earth?

That’s a problem that some NASA engineers are now working to solve.

After 18 years of capturing images of nearby galaxies and newborn stars, the hard-working Hubble Space Telescope mysteriously stopped sending data in late September.

The timing of the failure was unfortunate. It occurred just weeks before a shuttle mission to upgrade the aging space telescope was scheduled to blast off. That mission is now on hold until early next year while NASA engineers find ways to address the telescope’s recent problem.

The problem stems from a failure inside a data formatting unit, a device designed to receive scientific data from the telescope’s five main instruments and transmit this data to Earth. Without this unit, the Hubble is unable to capture and beam down information that is needed to produce the telescope’s breath-taking deep space images.

NASA was prepared for such an emergency, though, and had stowed a copy of the formatting unit onboard. However, immediately switching over to this backup unit could create new problems, says Preston Burch, Hubble manager at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md.

For starters, the switchover would require engineers to electronically reconnect all five main instruments. The change might also blow a fuse or cause additional failures for Hubble.

|

|

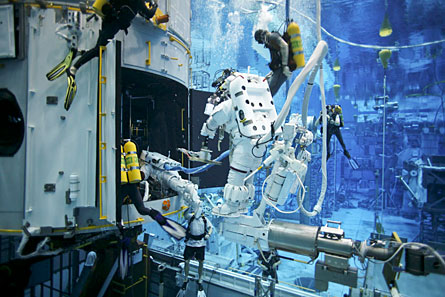

At NASA’s Johnson Space Center, astronauts practice repairs on an underwater, life-size replica of the Hubble Space Telescope. |

| JSC/NASA |

Instead, the Earth-bound engineers plan to tackle the job slowly. The first step, says Burch, is to practice making the switch on a replica of the Hubble system located on the ground at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center.

If all goes well on Earth, the engineers will then attempt to switch to the duplicate unit onboard the real Hubble in space. But even if it works, the switch to the duplicate system would be a short-term solution, Burch says.

To ensure that Hubble keeps going as long as possible, NASA plans to send some “roadside assistance” to space.

Astronauts may carry a duplicate data formatting unit into space when the recently delayed servicing mission launches next year. By replacing the failed data formatting unit with a new gadget, a spare unit could remain on Hubble in case of another failure, Burch says.

Still, this is no ordinary emergency repair job. The astronauts will have to replace the unit during a two-hour spacewalk 612 kilometers (380 miles) above Earth.

Going Deeper: