Analyze This: Moving frogs to new places helped an endangered species spread

Frogs resistant to a deadly fungus jump-started populations in these new areas

Mountain yellow-legged frogs used to live across California’s Sierra Nevada Mountains. The creatures’ numbers declined because of predatory fish people brought to mountain lakes and a deadly fungus. But some frogs evolved an ability to fight the fungus. Now researchers are using fungus-resistant frogs to start new populations.

R. Knapp

Share this:

- Share via email (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share to Google Classroom (Opens in new window) Google Classroom

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

A deadly fungus has been wiping out amphibians around the globe. But some frogs that have developed resistance to the disease are helping their species bounce back.

Mountain yellow-legged frogs used to live in lakes all over California’s Sierra Nevada Mountains. Their numbers started dropping in the past century when people brought into their habitat fish that eat frogs and tadpoles. Then in the 1970s, the deadly chytrid (KIH-trid) fungus arrived.

Mountain yellow-legged frogs went from being super abundant to being one of the rarest amphibians in the United States, says Roland Knapp. He’s a biologist at the Sierra Nevada Aquatic Research Laboratory in Mammoth Lakes, Calif. “By the early 2000s, the mountain yellow-legged frog was headed for extinction,” Knapp says. They’re now missing from more than 90 percent of the places where they used to live (called their historic range).

In some spots, though, a few frogs survived. Their immune systems developed a way to fight off the fungus. Those rare, resistant frogs passed on their ability to survive to their young, Knapp says. “In the matter of a few generations, you have evolution in the frogs for increased resistance against the chytrid fungus, which is amazing.” Some populations even thrived.

Knapp realized that these resistant frogs might be able to kick-start new populations. In 2006, he and his colleagues started reintroducing frogs to frogless habitats where their species had once lived. The researchers took frogs to areas they couldn’t get to themselves. For instance, where there were mountains or predatory fish in the way.

Over the past two decades, Knapp’s group has done more than a hundred reintroductions. After bringing frogs to their new homes, the researchers keep tabs on them, returning later to catch, identify and weigh them.

It took a long time before Knapp’s team could tell if their efforts were paying off. The reintroduced frogs needed not only to survive, but also to reproduce. And it takes six years for these frogs to mature to adults from eggs.

“After about 10 years from the first reintroduction, I finally convinced myself that this is working,” Knapp says. That was “the best day of my life,” he says. His team reported its results for 12 sites last November in Nature Communications.

Now that they know recovery is possible, the scientists want to reintroduce frogs to even more sites. They hope to boost mountain yellow-legged frog numbers across the species’ historic range — the entire Sierra Nevada Mountains.

This is Knapp’s mission, but he hopes his work will inspire others, too. “We can all decide in our own way how we want to make the world a better place,” he says. “For me, that meant bringing frogs back to a place where they used to be so abundant.”

Habitat-hopping frogs

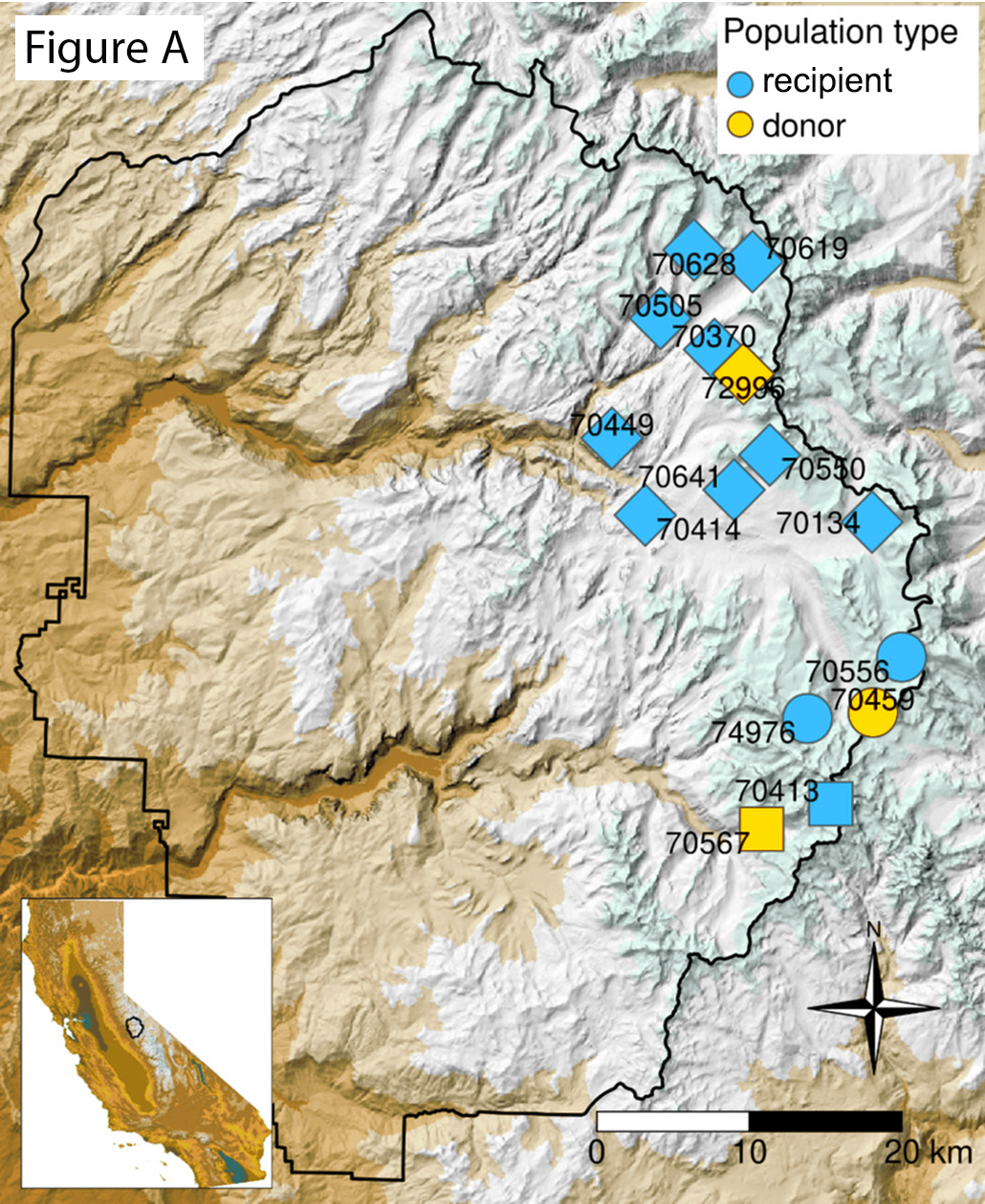

Mountain yellow-legged frogs include two species. One of those is the Sierra Nevada yellow-legged frog (Rana sierrae). In this study, Knapp’s team introduced new Sierra Nevada yellow-legged frogs 24 times to a total of 12 sites. These reintroductions, shown in Figure A, took place from 2006 to 2020.

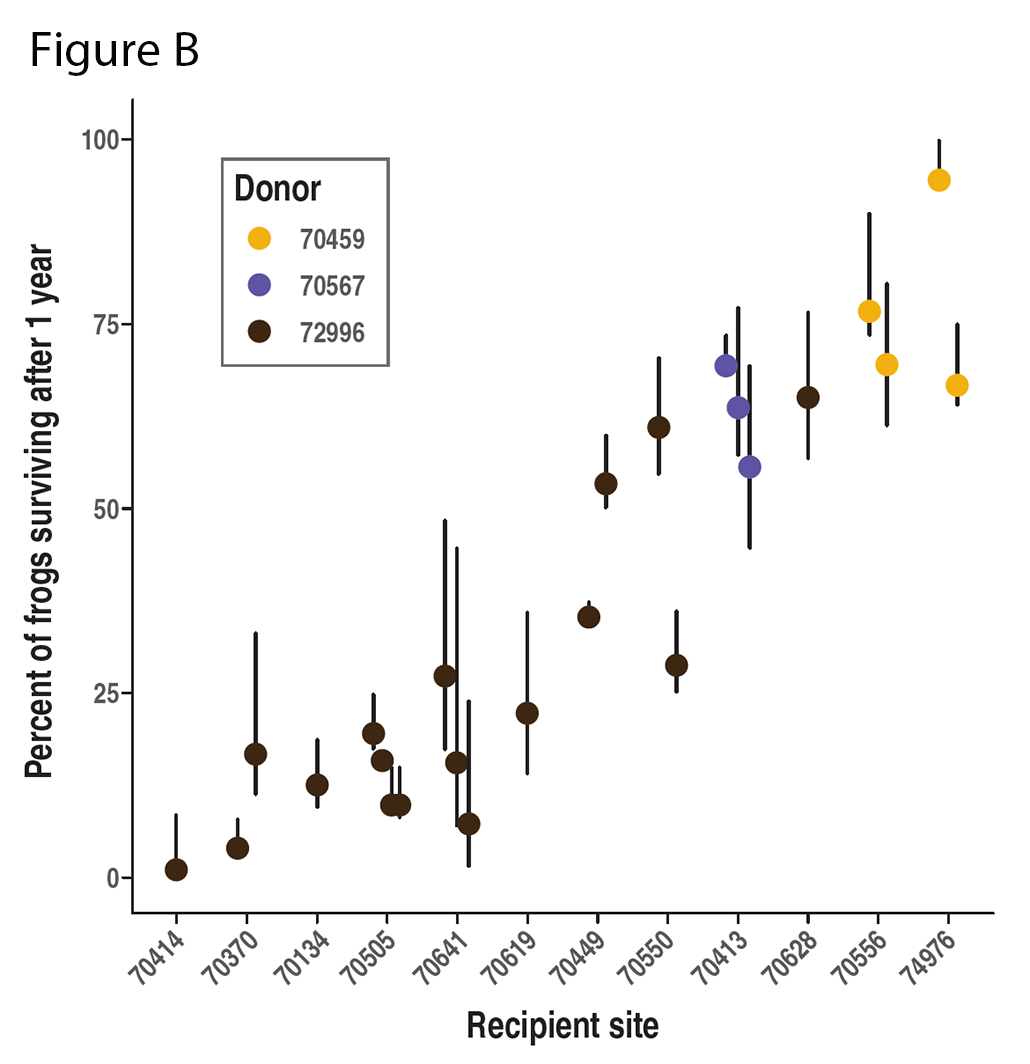

The scientists took frogs from “donor sites” (yellow markers). They moved these frogs to “recipient sites” where frogs were missing (blue markers). The shape of markers (square, circle, diamond) shows which donor sites the frog transplants came from. Each site has an identification number. Figure B shows the researchers’ estimates of how well transplanted frogs survived one year after they were introduced (different donor sites shown in different colors). Some sites have multiple data points because they had multiple frog relocations.

Data Dive:

- Look at Figure A. What’s the farthest that any frogs were moved? What’s the shortest distance frogs were moved?

- Which donor site is connected with the most recipient sites?

- Look at Figure B. How many sites have a one-year frog survival above 50 percent?

- Which donor sites are connected with the most successful recipient sites?

- What aspects of sites do you think may influence whether frog reintroductions are successful?