A new hydrogel could help pull drinking water from the air

The salty material absorbs record amounts of water, even from dry desert air

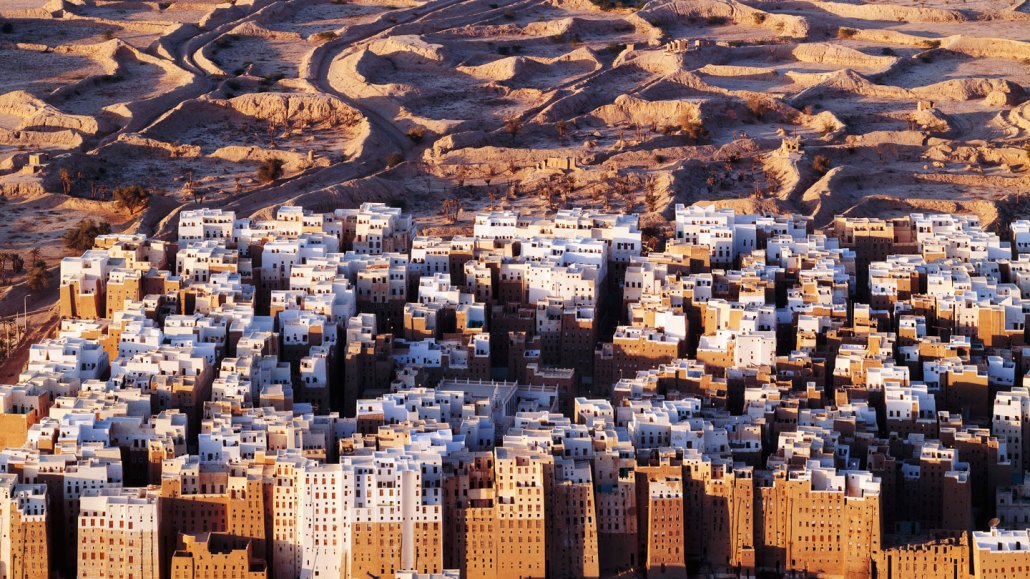

More than one-quarter of the world's people live without enough drinking water. Hydrogels that suck water from the air may be able to help provide a source of clean water in arid regions, such as this town in Yemen.

George Hammerstein/The Image Bank/Getty Images Plus

Share this:

- Share via email (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share to Google Classroom (Opens in new window) Google Classroom

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

By Laura Allen

This is another in our series of stories identifying new technologies and actions that can slow climate change, reduce its impacts or help communities cope with a rapidly changing world.

We all need clean water to survive. Yet across the planet, more than one in every four people live in places without enough. And climate change is making this worse. Now scientists have created a new salty gel. It sucks record-breaking amounts of moisture out of the air to make fresh drinking water — even in dry climates.

Carlos Díaz-Marín is a mechanical engineer at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge. His team is developing a device to address water shortages. They want it to affordably pull water from air without a need for electricity. The key ingredient: a new, super-salty gel.

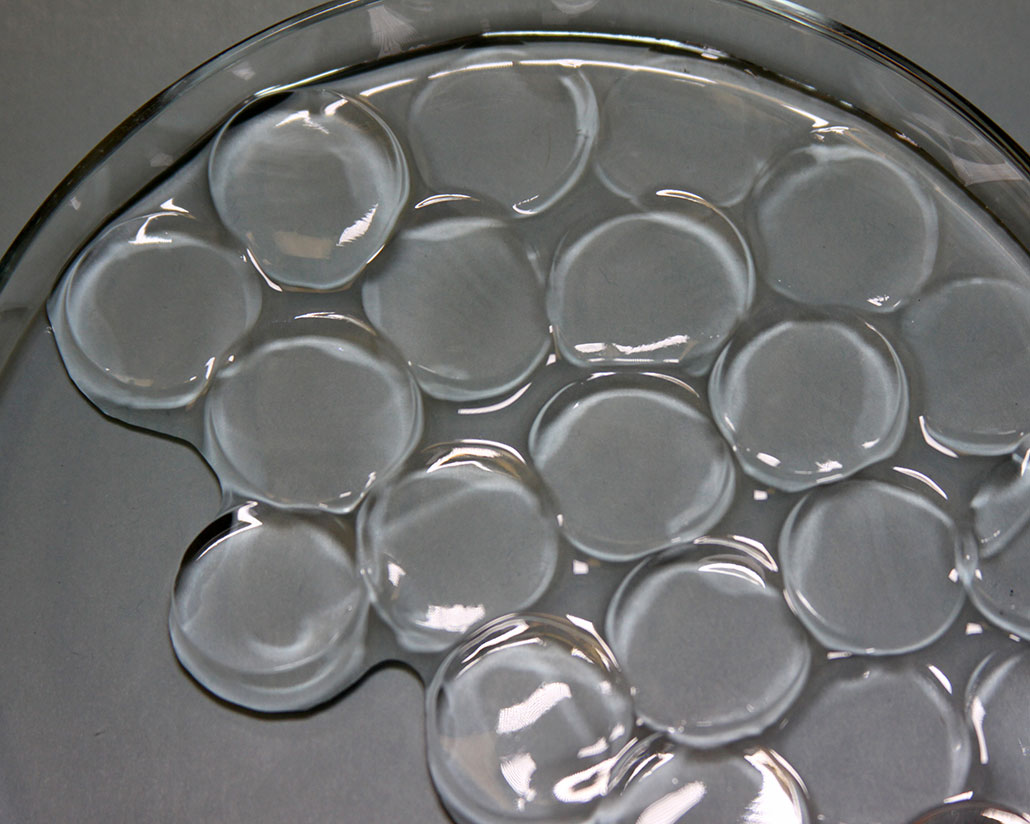

A hydrogel is a mesh of large molecules called polymers. The new hydrogel captures humidity — water vapor — from the air. As it does so, it expands like a sponge in water. Later, when heated by the sun, this material will release the water it has absorbed.

The idea is not new. Many types of hydrogels have been developed to suck water from air. Previous work showed that adding salts to hydrogels upped how much water they could absorb. Because of their chemical properties, salts attract moisture, including from the air. But no one knew how much salt a hydrogel could stash — nor how pushing that salt content to the max might boost the hydrogel’s water-slurping power. Díaz-Marín and his team decided to find out.

Getting salty

The researchers made tubes of hydrogel from a material called polyacrylamide (PAH-lee-uh-CRIH-lah-myde). That’s a polymer made of long, threadlike molecules. They cut the tubes into thin disks and then soaked them in water containing different amounts of lithium chloride, a salt. Each day, the researchers weighed the disks to see how much of the salty water they had absorbed.

Such tests had been done before, but for relatively short times, Díaz-Marín says. “Instead of soaking for two days, we did this for up to two months.” The extra time made a big difference.

The gels soaked up more and more saltwater over time. The top absorber got about three times saltier than previous hydrogels. It cached 20 grams (0.7 ounce) of salt per gram of gel. It absorbed more moisture than previous gels, too.

To test this, the researchers dried their gels and placed them in environments with different levels of humidity. Even in relatively dry air, such as that found in deserts, the best-performing hydrogel absorbed 15 percent more water than previous hydrogels.

The team reported its findings May 18 in Advanced Materials.

“We did this in a very simple and low-cost way, which makes it even more exciting,” says Díaz-Marín. His team still needs to test how to get all that water out of the gels afterward.

“I am impressed by their results,” says Swee Ching Tan. “This could be a new world record.” He’s a materials scientist at the National University of Singapore. Tan works with hydrogels but did not take part in this study.

The new work, he says, could help with the water crisis by producing safe drinking water in places that lack it.

More food, less water

Earth’s freshwater supply is falling due to climate change. By 2050, more than five billion people are expected to lack water at least one month per year. Some shortages are due to warmer temperatures and less snow to feed into rivers. That puts stress on supplies of water for drinking and growing crops.

Whatever the cause, better water-slurping gels could make it easier to grow food in such water-stressed places — including those plagued by drought.

Tan’s team has developed a gel-based device called the SmartFarm. This tiny greenhouse with a moving roof grows crops without having to add water. In the evening, the top opens. Gels inside capture water from the night air. A solar-powered motor closes the roof during the day. When warmed by the sun, the gel releases its water. Tan’s team used the SmartFarm to grow a leafy green vegetable called Ipomoea aquatica.

Some farmers have used hydrogels to water crops in another way. They mix the hydrogels right into the soil with seeds. There, the gel soaks up irrigation water and holds it close to the sprouting plant. Without the gel, water might soak too deeply for the roots to reach. In one study, adding hydrogels to soil reduced by 30 percent how much water was needed to grow food.

The MIT team is also designing a hydrogel-based device. Rather than grow food like the SmartFarm, it will produce drinking water. Díaz-Marín explains how it would work: At night, an open box containing their gel captures water vapor from the air. The next day, the sun heats up the hydrogel in the box, releasing the moisture. The box also contains a material that can be cooled without using electricity. When the water vapor touches that cold surface, it condenses into droplets — like the morning dew on grass. Once condensed, the clean water falls into a storage chamber.

The team is working to engineer a device that can extract 2 to 5 liters (0.5 to 1.3 gallons) a day. That should supply someone’s average drinking-water needs.

As places get drier, new sources of drinking water will be needed. It’s great that hydrogels can make water anywhere, says Díaz-Marín. For ultra-dry places with few other options, he says, they could be a lifesaver.