Scientists finally know why ice is so slippery

This common phenomenon had been misunderstood for at least two centuries

We all know ice is slippery, but the physical reason for this has remained a mystery for the past 200 years.

Imgorthand/Vetta/Getty Images Plus

Share this:

- Share via email (Opens in new window) Email

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share to Google Classroom (Opens in new window) Google Classroom

- Print (Opens in new window) Print

This is a human-written story voiced by AI. Got feedback? Take our survey . (See our AI policy here .)

Slippery ice is something most of us have encountered, whether it’s been under our boots, car tires or skates. But why ice is so slick has puzzled scientists for centuries. Now researchers in Germany offer a new explanation. They show ice can melt slightly with no heat added. It’s due to molecular-level changes that disrupt the crystal structure of ice.

For hundreds of years, people have tried to understand why ice is slippery. In the 1850s, Michael Faraday performed a now-famous experiment. This chemist and physicist showed that if you placed two ice cubes atop one another, eventually they’d lock together. Each had been coated in a thin layer of water, he explained. And that water froze when the cubes touched.

This didn’t show, however, why ice was covered in that thin layer of water.

A few years later, an engineer named James Thomson offered an explanation. Pressure, like heat, can melt ice. Using math, he showed that the pressure from a boot, say, or skate blade could melt a small amount of the ice. That could form the thin layer of water.

But there was a problem with this explanation.

The pressure from a boot wouldn’t melt enough water for the ice to turn slippery. You’d need to concentrate all of someone’s weight on a very small area to do that. How small? About the size of a poppy seed.

Almost a century later, in 1939, a pair of physical chemists came up with another idea. Pressure and heat together could melt ice to create a slippery layer of water, they suggested. This heat could develop from the friction of a boot or other object traveling over the ice.

But even this explanation fell short. Why? Ice remains slippery even at sub-freezing temps. And so the slick mystery persisted.

In 2024, researchers at Peking University in Beijing, China, explained why some of the water layer forms. Tiny defects in the surface of ice, they found, can create a thin layer of water on top of it. In fact, notes Martin Müser, that team showed that “even at an extremely cold temperature, there is some initial water on the surface.” However, Müser argues, that water layer is not thick enough to make ice truly slippery.

Müser’s team at Saarland University in Saarbrücken, Germany, now offers a different, but related, explanation. To figure it out, these materials scientists modeled what happens to ice at the molecular level.

When ice gets ‘frustrated’

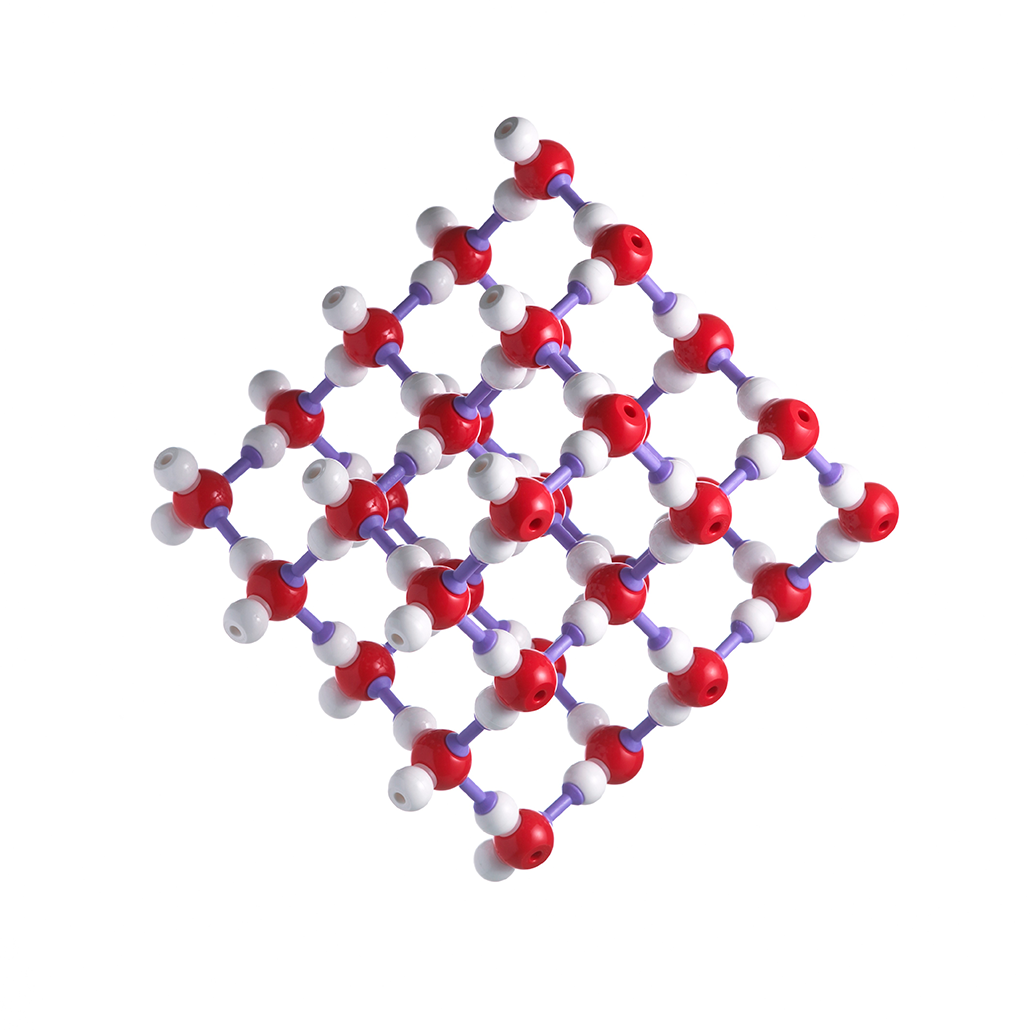

Ice is a crystal. This means its molecules are arranged in a neat pattern. With his team, Müser created a computer model of ice. Then they watched how properties of its molecules would change when the model had a sheet of ice touch another surface (such as a boot, tire or skate).

Water is a dipole molecule. That means one side has a slight negative electric charge; the other side is positively charged. That charge separation makes the molecules in ice line up in a regular structure — like little magnets.

Yet it doesn’t take much to disrupt that ordered structure. Imagine a boot touching the ice. Dipoles within the boot itself will attract dipoles in the top layers of the ice. It’s like two magnets attracting one another.

As the boot moves, the dipoles in the ice move, too. Now the perfect crystal structure of ice begins to fall apart as more and more of its molecules step out of line.

This process is called frustration, says Müser. The ice “kind of melts without really heating.”

The molecular changes shown by the new simulations would be virtually impossible to physically observe, the researchers note.

Müser likens crystalline ice to “an ordered bed of shell pasta.” Imagine, he says, what would happen if “now you rub over it with a slightly sticky hand.” Some shells will get pulled out of order. The dipoles in the boot or tire provide a similar stickiness to pull ice molecules out of order.

The affected molecules no longer behave like a crystal. Instead, they become that thin layer of water atop the ice.

A melt — with no heat needed

This is not the traditional way ice melts. It usually melts due to pressure or heat. But in this case, solid ice changes into liquid water as defects mess up its crystal structure.

“This means ice can be slippery even at low temperatures,” says Lars Pastewka. He’s a microsystems engineer at the University of Freiburg in Germany. Indeed, the Saarland computer model shows that “frustrated” ice will remain slippery at 10 kelvins. That’s –442º Fahrenheit, or close to absolute zero.

“Molecular simulations like these have the power to show what every atom is doing,” says Robert Carpick. That “is why [this new model’s] results should be taken seriously.” A mechanical engineer, Carpick works at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

Pastewka’s group has shown similar crystal defects in silicon and diamond. This can turn their surfaces slippery, too. Diamond has one critical difference, though. With water ice, “the harder you push, the easier it gets to turn it into a liquid-like goo,” Pastewka says. In diamond, you get the opposite effect — which actually protects the surface.

In theory, you could skate on diamond for the same reason you can on water ice. But you wouldn’t leave as many marks on the surface of a diamond rink.

So what’s the solution to keep you from slipping on ice in winter? “I would say, put on cleats,” says Müser. “That’s really the only way.”

Do you have a science question? We can help!

Submit your question here, and we might answer it an upcoming issue of Science News Explores