‘Stenciling’ tiny gold particles gives them new properties

Scientists borrowed the technique from a popular style of decorating pottery

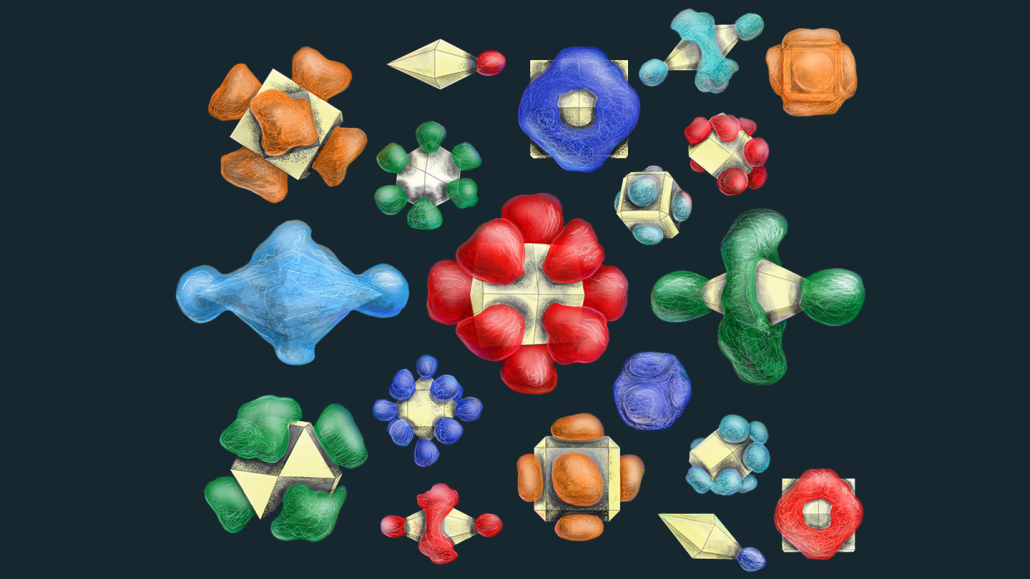

These drawings show some of the designs that scientists could stencil onto tiny gold particles. Using a mixture of chemicals, a team of researchers made more than 20 different patterns on the nanoparticles.

Maayan Harel

Share this:

- Share via email (Opens in new window) Email

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share to Google Classroom (Opens in new window) Google Classroom

- Print (Opens in new window) Print

By Skyler Ware

This is a human-written story voiced by AI. Got feedback? Take our survey . (See our AI policy here .)

A popular technique for decorating pottery is helping scientists “paint” intricate patterns on nanosized bits of gold. This teeny tiny art technique could give the gold specks exciting new properties.

The new nanoparticles could have a wide range of uses. They could go into tiny electronic circuits. They could help tote drugs to specific parts of the body. They could even assemble themselves into “metamaterials.” Such materials might interact with light or sound in new ways.

But building the right types of nanoparticles for such jobs is no easy feat. Scientists must carefully craft the particles’ surfaces. This controls how they will interact with each other and with other things. That’s quite difficult when each particle is less than 100 nanometers across. That’s just one-thousandth as thick as a typical sheet of paper!

Nanoscientist Ahyoung Kim got her idea for this solution in a pottery class. Kim used handmade stencils to decorate her pieces. First, she drew a design on the ceramic pottery with wax. Then, she colored over the pot with ink. That ink stuck everywhere except where the wax was, leaving the design behind.

Kim had been trying to find a way to decorate nanoparticles of gold. Scientists had reliable ways to make the tiny gold bits, but not decorate them. “At that point, I thought, ‘Oh, maybe I need some kind of mask-like thing’” — like the wax she used on pottery. Kim stenciled nanoparticles as a student at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Now, she’s working at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena.

Super-small stencils

Kim was part of a team that used chemicals to carefully stencil patterns on nanosize nuggets of gold. The gold bits were too small to draw on with wax. So she used something called iodide. When she mixed it with the nanobits, the iodide covered some parts of the gold, but left other areas exposed.

Kim also added a material called 2-NAT. It stuck to the still-exposed gold surfaces, but not to areas covered with iodide. Finally, she “painted” the gold nanobits with long, hair-like chemicals. A type of polymer, they clung to areas covered with 2-NAT, but not to areas covered with iodide. The iodide had acted like the wax stencil in her pottery class, limiting where the polymer “paint” could stick.

By changing the amounts of iodide and 2-NAT, the team could stencil nanoparticles with different designs. The shapes of the particles also affected those final designs.

Computer models helped predict what the designs would look like with different recipes of gold, iodide and 2-NAT. These simulations also predicted how the gold bits would arrange themselves into larger structures. After running those models, the scientists whipped up more than 20 of the designs in the lab.

This stenciling is “pushing the frontiers of what’s possible with nanocrystals and how they can be modified,” says Sara Skrabalak. She’s a chemist at Indiana University Bloomington. Skrabalak did not take part in the new study. But she does work with other tiny materials.

Kim’s team described its tiny stenciling trick in the October 16 Nature.

Many designs — and many uses

Gold nanobits can group to make bigger structures. And different stencils affect how.

Normally, gold nanobits cluster closely, like a stack of oranges at the grocery store. But with the polymer patches stenciled on, that changes. The polymers stick out from each gold bit, pushing other gold nanobits away. Instead of packing tightly, the stenciled gold bits pack more loosely. That could change some of their traits.

For instance, it might change how they interact with light, says Maria Rosaria Plutino. She studies nanoscale materials at the Italian National Research Council in Messina. Rosaria Plutino did not take part in the new research. She does, however, study how tiny particles like these might work in fabrics, medicines and other applications. Adding stenciled nanoparticles, for example, might change a fabric’s color, she says.

Do you have a science question? We can help!

Submit your question here, and we might answer it an upcoming issue of Science News Explores

And that’s just the beginning. Researchers might stencil nanobits with different polymers and decorate metals other than gold.

Such stenciled nanobits might help make stealth coatings, Skrabalak says. These might hide things from radar, making them harder to spot.

Kim says her team is now exploring combos that could affect how medicines react in the body. The goal: Use the stencil to help direct a drug to where it’s needed.

“It’s a very nice approach,” Rosaria Plutino says. “It opens a lot of different ways to apply this kind of stencil.”