Earth’s lowly rumble

From rumbling volcanoes to grumbling elephants, scientists are eavesdropping on the lowest sounds on Earth.

Share this:

- Share via email (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share to Google Classroom (Opens in new window) Google Classroom

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

Earth is an incredibly noisy place. Avalanches roar down mountains, volcanoes rumble, and hurricanes blast through coastal areas. And while there’s a whole range of sounds that people can hear, there are also Earth sounds that are too low for the human ear to pick up.

|

|

TV crews wait for Mount St. Helens to erupt. Sound at low frequencies that people can’t hear could provide a warning that such a volcanic eruption is about to occur.

|

| Kate Ramsayer |

These silent sounds, or infrasound, are calling to some scientists. These researchers are using special microphones to eavesdrop on infrasound created by the world around us. The noisemakers include volcanoes, tsunamis, hurricanes, and even the turbulence that shakes airplanes.

“We’re learning more about how the planet operates by listening,” says Michael A. Hedlin. He studies sounds at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in La Jolla, Calif.

Low notes

Like all types of sound, infrasound travels in waves. The sound waves have different heights, or amplitudes, which make them louder or softer. They also have different wavelengths, measured from the crest of one wave to the top of the next. And they have different frequencies, measured by the number of crests that pass by a particular position per second.

Short, rapid waves make high-pitched sounds, like a teapot’s whistle. Long, slow waves make low-pitched sounds, like a bass guitar in a rock band. And below the lowest note on a bass, below what people can hear, there’s infrasound.

|

|

An elephant generates and probably detects infrasound.

|

Infrasound is created when something, such as a bomb explosion or an earthquake, sets a large amount of air in motion. The resulting sound waves travel through the air, sometimes for thousands of kilometers.

Scientists originally started studying infrasound to make sure faraway countries weren’t testing nuclear bombs. Now, they’re using infrasound to check for natural events.

“We’re finding all these exotic sources [of infrasound] that we hadn’t thought of before,” Hedlin says.

Tsunami sounds

One of those infrasound sources is a gigantic wave called a tsunami. “We didn’t know that a tsunami produces infrasound,” says Milton Garcés. He runs the infrasound laboratory at the University of Hawaii, Manoa.

|

|

Earthquakes under the ocean can generate tsunamis. Special instruments on buoys, such as this one, can detect the resulting waves.

|

| National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration |

When a massive earthquake occurred off the coast of Indonesia in December 2004, for example, it sent a deadly wave across the Indian Ocean. When Garcés looked at infrasound data that were recorded near the tsunami, he found a big signal that corresponded to the wave. “It produced a wallop,” he says.

In the last year, Garcés and his colleagues have picked up sounds from two more tsunamis. One was a Japanese tsunami that produced “beautiful infrasound,” he says.

The researchers recently set up a tsunami infrasound project in Hawaii. “Whenever there’s a tsunami, we’re going to be looking at it very carefully,” Garcés says. The scientists hope to learn how the giant waves produce infrasound, which is currently a mystery.

Volcano rumbles

Garcés and others are also using infrasound to listen in on volcanoes.

On the Sakurajima volcano in Japan, Garcés discovered that stronger and stronger infrasound signals led up to the volcano’s eruption in 1998. If this happens all the time, scientists could use infrasound patterns to warn people if a nearby volcano is about to blow, he says.

|

|

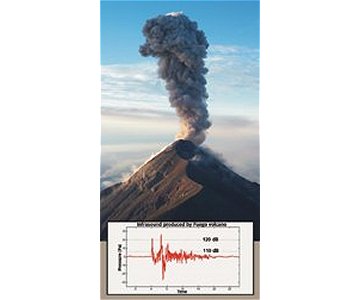

The eruption of the Fuego volcano in Guatemala in 2003 generated strong infrasound, mostly below a frequency of 10 hertz (cycles per second). The pressure readings show that the strength of these sound waves can reach the equivalent of 120 decibels (roughly the loudness of an ambulance siren, heavy machinery, or a rock concert). |

| Jeffrey B. Johnson, University of Hawaii at Manoa |

Detecting volcanic eruptions with infrasound would also be a useful tool for airplane pilots, because ash from an erupting volcano can dangerously damage a plane’s engines.

Infrasound stations are also keeping an ear on Mount St. Helens in Washington State. Hedlin can tell that gas is bubbling up in the volcano just by looking at the infrasound recordings.

The recordings also detect small earthquakes inside the volcano that push air around, as well as other events whose causes are yet unknown. Infrasound gives researchers a more complete picture of how volcanoes work, Hedlin says.

And scientists are always listening for new things to investigate, Hedlin adds.

Hedlin has recorded infrasound coming from sprites, which are short flashes of light in the atmosphere above thunderclouds. He’s also planning to set up a station to study winds off the coast of Africa, where hurricanes begin to form. To listen to the speeded-up sound of a sprite (so that you can hear it), click here.

|

|

The northern lights (auroras) generate infrasound by pushing the surrounding air outward.

|

| Collection of Dr. Herbert Kroehl, NGDC, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration |

Other researchers are using infrasound to detect avalanches, the northern lights, ocean waves, bumpy air that causes airplane turbulence, and mountains shaking from earthquakes.

Animal calls

While people are deaf to infrasound, other animals appear to use it to communicate. When elephants trumpet, for example, they also produce infrasound that can reach other elephants as far as 10 kilometers away, researchers discovered.

Elephants might even pick up these low rumblings through their feet, says Caitlin E. O’Connell-Rodwell. She’s a scientist at Stanford University in California.

Other researchers have suggested that whales, rhinos, and big birds called cassowaries can create or pick up infrasound. Even some dinosaurs might have had this ability.

|

|

A cassowary might pick up ultrasonic signals with its casque, a mysterious structure on top of its head. No one is yet sure what this structure is for.

|

| Andrew L. Mack, Wildlife Conservation Society |

In addition, it’s possible that people can detect infrasound in special ways. When elephants trumpet, “it’s such a powerful, low-frequency sound,” O’Connell-Rodwell says. “You really feel it resonating in your chest.”

In one experiment, researchers in England played infrasound during a music performance. Although listeners couldn’t hear the super-low notes, they seemed to have stronger emotions during the performance than did people who heard music without infrasound.

There certainly seems to be more to infrasound than meets the ear.

Going Deeper: