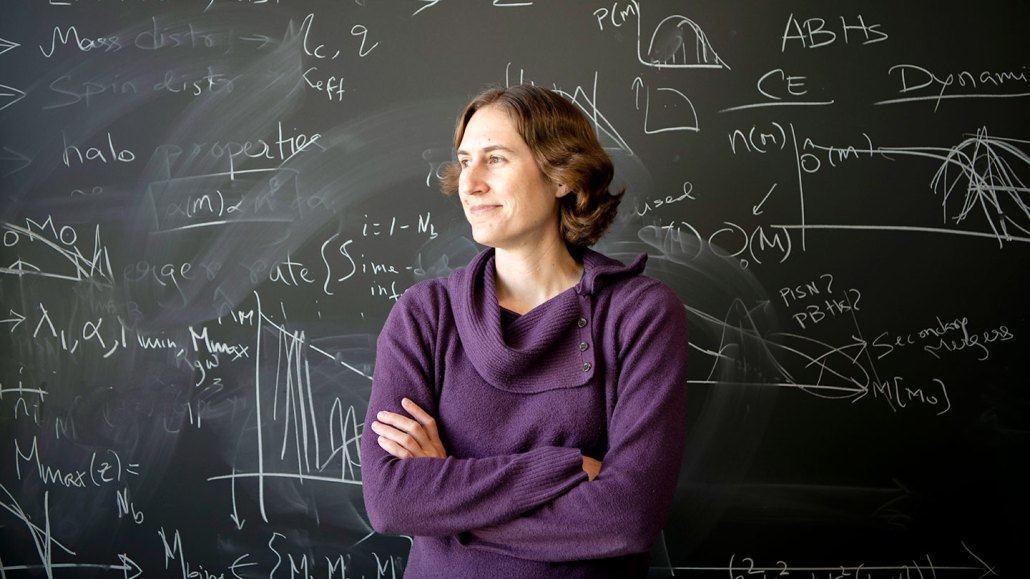

This cosmologist studies the invisible parts of the universe

Katie Mack studies dark matter to better understand how galaxies form and evolve

Cosmologist Katie Mack studies dark matter, an invisible substance that researchers suspect holds the universe together. Teasing out the identity of this elusive matter can help researchers better understand the universe’s beginnings and its possible end.

K. Mack

Share this:

- Share via email (Opens in new window) Email

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share to Google Classroom (Opens in new window) Google Classroom

- Print (Opens in new window) Print

This is a human-written story voiced by AI. Got feedback? Take our survey . (See our AI policy here .)

Before Katie Mack became a scientist, she was the kid taking apart TV remotes and building solar-powered cars out of LEGOs. “I’d take things apart and put them back together to figure out how they work,” she says. This tinkering kick-started her love of science.

But Mack wouldn’t come across her future career until she was about 10 years old. That was when she read A Brief History of Time by physicist Stephen Hawking. His explanations about black holes and the Big Bang inspired Mack to figure out how the universe works. When she found out Hawking was a cosmologist, she says, “I became convinced that I wanted to be one, too.”

Now a cosmologist herself, Mack studies invisible material known as dark matter at the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics in Waterloo, Ontario, in Canada. While dark matter doesn’t absorb or emit light, it can affect objects with its gravity. “So we have this idea that dark matter is out there, but we don’t know what it’s made of,” she says. But researchers suspect it helps hold the universe together.

Sleuthing out dark matter’s true identity can help answer larger questions about the universe, says Mack. These include better insights into how galaxies form and evolve over time. In this interview, Mack shares her experiences with Science News Explores. (This interview has been edited for content and readability.)

Who were some of your role models growing up?

When I was younger, my mom was working toward her Ph.D. in nursing. She trained as a nurse and worked in hospitals but also did clinical research around treating cancer. I learned a lot from her about how science and research work.

Also, my grandfather was a meteorologist in the Navy. He served on the Apollo 11 mission. His job was to make sure that the location of the splashdown after the mission would be safe. It turns out that there was a big storm at the original site planned for the splashdown. So they moved the site because of that. When you’re coming down on the parachutes, it’s important not to have a storm.

Sometimes, I’d see scientists on TV. Whenever there was an earthquake, one of our local seismologists, Kate Hutton from Caltech, would talk about it. It was inspiring to see a scientist talking to reporters about how the world works. Having that personal connection with scientists is very valuable. It helps the public better understand how science works and how we know what we know.

What are some misconceptions about the work that you do?

One of the biggest things that I encounter when I talk about dark matter is people saying that it’s not real. They assume it’s just a mistake somewhere in the math or that scientists need to rethink gravity. People often bring this up as though we haven’t thought about that. They assume scientists just had a cool idea and ran with it. That’s not really how it goes.

When trying to come up with an explanation for some phenomenon, scientists compare different possible models at every stage. We really try our best to come up with all possible ways of thinking about the problem. If we reject one, it’s because it doesn’t fit the data.

At the same time, I think physicists are very often more creative than people realize. We’re not just grinding through math. People sometimes suggest that we’re set in our ways. That we’re not trying out new ideas. But nobody’s going to get the Nobel Prize for that. The findings that make a big splash are not the ones saying that everyone was right in the first place.

What piece of advice do you wish you’d been given when you were younger?

I would give myself a little encouragement and tell myself that it’s OK if what I’m doing is really hard. That doesn’t mean that I wasn’t cut out for it.

A lot of people get really discouraged as soon as they find that they’re having trouble in a field. They assume that it should come easily if it is going to be their career. I don’t think that’s necessarily true. It’s OK to not be born good at something. You can learn and develop your skills. Just because something is much harder for you than your classmates doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t do it.

I think so many kids get the idea that all scientists are these super geniuses. That you can tell someone is a scientist just by how they look or talk. In the media, you can tell which one is a scientist because they have a certain look, attitude or way of speaking. A lot of kids can’t relate to that. It convinces them that they can’t be scientists. That really does people a disservice. The scientific community is much more diverse than that.

What have you found challenging about your field?

One of the big challenges in my field is just sticking with it. In physics, more people want to do academic research than there are jobs. If you’re applying for a postdoctoral fellowship, oftentimes there will be 300 people applying for one position. That makes it quite hard to progress.

And when you get to faculty jobs at colleges and universities, it’s even worse. Most people who get Ph.D.s in physics do not end up with faculty positions. That means sticking with it may not always be the best option. Figuring out how to pivot to something else if your plans don’t work out becomes really important, yet difficult to make happen.

Faculty jobs also require a lot of relocating to different institutions or even countries. I’ve had to move to a new country at every stage of my career since I started graduate school. On one hand, it’s a privilege that I’ve been able to live, say, in Australia for five years and England for three years. But it can also be really challenging in other ways. Starting all over again in a new place can be really lonely. Making all of those sacrifices can make it difficult to stay motivated and engaged.