Earth’s poles in peril

Scientists are paying increased attention to changes in Earth's polar regions, which are in danger because of global warming.

Share this:

- Share via email (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share to Google Classroom (Opens in new window) Google Classroom

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

By Emily Sohn

The North and South poles are remote and frigid places that receive lots of animal visitors but few human tourists.

|

|

The polar bear is one of the few species to visit the North Pole.

|

| iStockphoto |

But even if you never plan to visit the polar bears in the north or penguins in the south, now is a perfect time to start thinking about them. That’s because 2007 marks the beginning of the International Polar Year (IPY), a two-year-long bonanza of science projects that aim to illustrate how important the poles are to the health of our planet. During the IPY, which will last until March 2009, thousands of researchers from more than 60 countries will conduct more than 200 projects and expeditions to both the top and bottom of the world.

In recent years, the polar regions have begun to change drastically as a result of global warming. Temperatures there are rising faster than anywhere else on Earth. As a result, the ice and snow in these regions are melting at record-setting rates. One result is that sea levels are rising around the world, putting animals and people at risk.

|

|

The extent of ice in the Arctic is steadily shrinking. In this diagram, land masses are in green (with North America on the left and Asia on the right). Water is in dark blue. The pink line indicates the average wintertime ice extent from 1979 to 2000. The current ice extent is indicated by the solid off-white area inside the pink line.

|

| National Snow and Ice Data Center’s Sea Ice Index |

Only by studying the poles, say IPY researchers, can we find ways to protect them and ourselves.

“The more we know about what is going to happen,” says Stephen Rintoul, an oceanographer at Australia’s Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization (CSIRO), “the more convincing the argument is to look at what we can do.”

Melting ice in the far north

Both the Arctic (in the far north) and the Antarctic (in the far south) are cold and remote, but the two regions have important differences, says biological oceanographer Louis Fortier of Laval University in Quebec, Canada. For one thing, the Arctic is an ice-covered ocean surrounded by land. The Antarctic, on the other hand, is a continent of ice-covered land surrounded by water.

|

|

Antarctica is a continent of ice-covered land surrounded by water.

|

| iStockphoto |

Most polar studies have focused on the Arctic, and that is where scientists have observed the most dramatic changes in the ice. During a typical year, Arctic ice expands in the winter and shrinks in the summer. But recently, the amount of ice covering the ocean has been steadily dropping in both seasons.

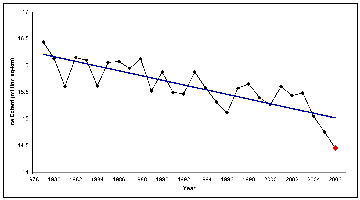

In the winter of 2005–2006, the winter ice mass hit an all-time recorded low for the second year in a row. The ice cover that year dropped 300,000 square kilometers (116,000 square miles), or 2 percent, from the previous year to a new low of 14.5 million square kilometers (5.6 million square miles). The amount of ice lost equaled the size of Italy.

|

|

The blue line shows the downward trend since 1979 of how much sea area is covered by ice. The extent of sea ice in March 2006 (indicated by the red dot) is 1.2 million square kilometers (463,000 square miles) less than the average ice extent from 1979 to 2000.

|

| National Snow and Ice Data Center |

In 2005, the summer low in the Arctic was 30 percent less than the low 20 years earlier.

|

|

Computer models show that summertime ice in the Arctic Ocean could vanish during this century.

|

| iStockphoto |

The rate of change

As more ice melts as a result of rising global temperatures, the rate of melting will most likely speed up as well. That’s because a sheet of ice acts like a huge mirror, reflecting sunlight back into space. But as the ice cover shrinks, the expanse of open ocean grows. Ocean water is darker than ice. Rather than reflecting the sun’s energy, it absorbs a lot of it. This causes the ocean to warm, which in turn hastens ice melting, which leads to even more open waters. The cycle continues–until all the ice is gone.

Most models, taking into account increasingly rapid melting, show an icefree Arctic summer happening as early as 2040, Fortier says, but some are more pessimistic.

“Most specialists believe we’ve reached the tipping point, after which things will accelerate very quickly,” he says. “Some models say the Arctic Ocean could be ice-free for a week or a month at the end of summer by as early as 2015.”

Satellite data shows that as much as 36 cubic miles of ice is melting in Antarctic each year, scientists announced last year. And NASA recently produced evidence that, in January 2005, unusually high temperatures led to the largest Antarctic snowmelt in three decades.

Life in the deep south

Disappearing ice could be devastating for wildlife in many ways. As the ice melts, water drains into the oceans, diluting them and making them less salty. That, along with warmer water temperatures, can harm the diverse creatures that live in, under, and near the ice, says zoologist Michael Stoddard, Chief Scientist with the Australian Antarctic Division. Cold-adapted animals—including polar bears, foxes, hares, and seals—also need ice for travel and survival.

Most species of fish, worms, sea spiders, and other animals, plants, and other organisms that live in the waters of Antarctica don’t live anywhere else, Stoddard says. Many of these creatures have special proteins in their bodies that keep them from freezing to death and have other adaptations to the cold that have yet to be explored.

|

|

Aboard research ships, scientists are exploring the far southern waters.

|

| iStockphoto |

Scientists such as Stoddard have learned a good deal about Antarctica. But overall, research on animal diversity in the area has been scarce. To learn more, scientists on a fleet of research ships are using underwater robots, cameras, and other high-tech equipment to see what else lives in these far southern waters.

A recent 10-week expedition turned up 15 potentially new shrimplike species, 4 potentially new corallike species, and lots of sea cucumbers, sea squirts, sponges, and more. Results of this IPY-timed census will help scientists track changes in these creatures.

“We want to look at everything from the 6 thousand million tons of plankton down to the insignificant, paltry organisms like penguins,” Stoddard jokes. Seriously, he adds, “we don’t know a lot about the Antarctic. We’re hoping the census will be able to fill up some of these holes.”

|

|

Being large, polar bears are relatively easy to count. Conducting a census of smaller organisms is more challenging.

|

|

iStockphoto

|

During the IPY, other groups are studying caribou, wolves, shrubs, and underwater mountains in the Arctic, microbes, krill, algae, and penguins in the Antarctic, and every other aspect of biology, geology, and ice-themed research you can imagine.

Saving the ice

As studies on the impact of climate change on the polar regions continue, experts are urging us to reconsider the way we live. The fossil fuels that we burn in cars, power plants, and factories are largely to blame for the carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases that are trapping excess heat in our atmosphere. If we can produce fewer of these gases, we can help save the polar ice. And saving the polar ice will help protect the oceans and us.

Biking, walking, and taking public transportation, for example, are pole-friendly activities. Encourage your parents to switch to efficient, compact fluorescent light bulbs, and turn the lights off in rooms when you’re not using them. Urging your politicians to fight for the environment can help too.

“Small things would make a difference,” Rintoul says, “if everyone did them.”

Going Deeper: