Mice show us why food poisoning is so hard to forget

Flavor memories processed in their brains help them avoid foods that once made them sick

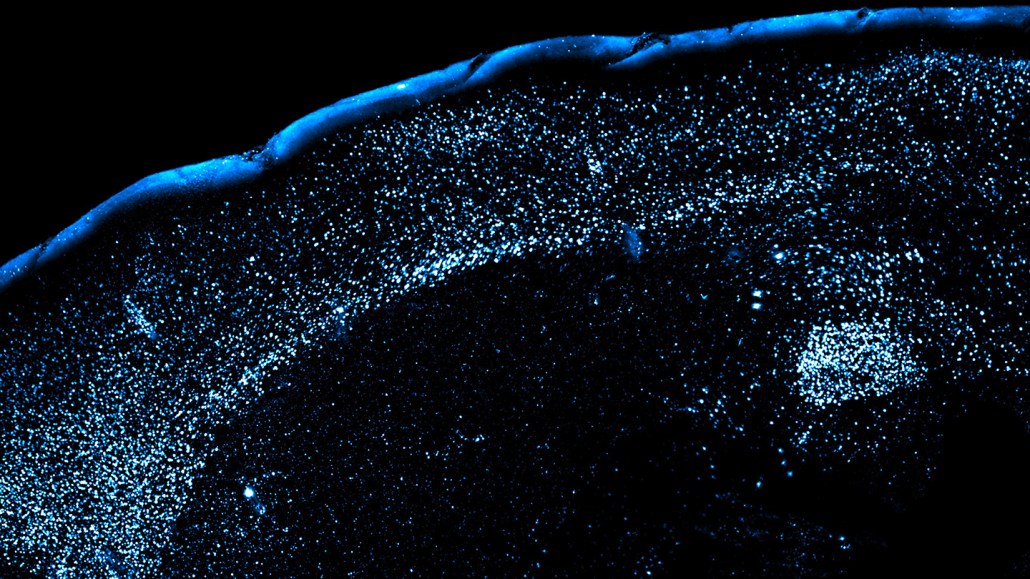

When mice eat something unfamiliar, neurons in a brain region called the amygdala light up (blue). If these mice later start feeling sick, the same neurons turn on again. This helps the mouse remember — and avoid — that food in the future.

Princeton University

Share this:

- Share via email (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share to Google Classroom (Opens in new window) Google Classroom

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

By Elise Cutts

Food poisoning isn’t something we easily forget. Scientists have now homed in on what makes it so unforgettable. Alarm cells lock the experience into our brain’s circuitry as a yucky memory. That’s the finding of a new study on mice.

Many of us have eaten something that left us sick. “Not only is it terrible in the moment, but it leads us to not eat those foods again,” notes Christopher Zimmerman. He’s a neuroscientist at Princeton University in New Jersey.

Getting sick just one time after eating an undercooked enchilada or burger can make us hate that food forever. And the food repulsion it triggers can develop even if it takes hours or days to start feeling sick after the meal.

Many other animals, it turns out, respond the same way.

Mice usually need an immediate reward or punishment to learn something, notes neuroscientist Richard Palmiter. He works at the University of Washington in Seattle. Even one minute’s delay between cause (say, pulling a lever) and effect (getting a treat) can be too long for mice to learn the two are related.

Not so for food poisoning. Even a rodent’s brain has no trouble linking a tummy torment now with something it ate quite a while earlier.

That makes food poisoning one of the best ways to study how our brains connect events that are separated in time, Palmiter says.

So researchers asked: How does the brain learn to hate foods that made us sick? After five years of experiments, Zimmerman’s team now shows that effects in the brain can burn dangerous tastes into memory.

They described the details in the June 19 issue of Nature.

Do you have a science question? We can help!

Submit your question here, and we might answer it an upcoming issue of Science News Explores

Important cells trigger alarms of danger

A small, almond-shaped brain region called the amygdala links emotions to memories, learning and our senses. So it’s not surprising that this region plays a role in deciding what flavors we find gross or not.

Palmiter’s group had shown that the gut tells the brain when it’s feeling icky. How? It activates certain “alarm” neurons called CGRP cells. “They respond to everything that’s bad,” Palmiter explains.

To study how alarm neurons link food poisoning to food repulsion, Zimmerman’s team at Princeton had mice drink grape Kool-Aid. A half-hour later, they injected the animals with lithium chloride. This made them ill. Two days later, they again gave the mice grape Kool-Aid.

The team ran versions of this simple experiment again and again. And at each step, they peeked inside the brains of those mice to see what was happening.

When the mice had first gotten sick after drinking grape Kool-Aid, their alarm neurons turned on. This event increased the sensitivity of amygdala cells that carried memories of the grape flavor.

Those same amygdala cells also turned on when the mice encountered grape Kool-Aid again. This suggests alarm neurons had helped the amygdala remember foods that seemed dangerous.

This effect didn’t show up in mice that had tasted grape Kool-Aid before without getting sick.

In people, things may not be as simple

The novelty that cues humans to remember food poisoning could rely on a bit more than just taste. Many unusual aspects of an eating experience can ick us out. It could be some spice blend. Or we may not like smells or other things that we pick up on in a restaurant that’s new to us.

The new study was largely motivated by “pure curiosity,” says Ilana Witten at Princeton. She’s a coauthor of the study. And her team’s findings might go beyond food poisoning, she now suspects. They might be “very relevant to mental health.”

Similar nerve pathways likely explain why unusual and bad experiences become so memorable, she says. But this event-triggered repulsion — known as aversive learning — sometimes goes wrong in people who have suffered a trauma or who have developed some addiction.

The brain wiring that’s supposed to keep us safe can now end up causing harm. Learning to control those circuits, she says, might point to new treatments.