How to be heat-safe when playing sports

Protecting young athletes from overheating is becoming more important as the climate changes

In hot, humid conditions, many young athletes are at risk of overheating. Hydration, breaks and other strategies can help keep players safe.

Rebecca Nelson/ DigitalVision/Getty Images

Share this:

- Share via email (Opens in new window) Email

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share to Google Classroom (Opens in new window) Google Classroom

- Print (Opens in new window) Print

By Megan Sever

This is another in our series of stories identifying new technologies and actions that can slow climate change, reduce its impacts or help communities cope with a rapidly changing world.

Twelve-year-old Theo was excited when his soccer team made it to a regional tournament last June. But when Theo took the field for his first game, something unexpected happened. The temperature that afternoon was above 32° Celsius (90° Fahrenheit) and humidity was high. Within minutes, Theo started to feel woozy.

He was sweating a lot. He also got dizzy and experienced nausea. “It got really hard to hear. I couldn’t really tell who or where the voices were coming from,” Theo recalls. “I looked around and [everything] was really blurry.” Then Theo went down on one knee and signaled to the coach that he needed to come out of the game.

At the medical tent, medics poured cold water over Theo’s head. He soon began to feel better. But he had to sit out the rest of the game in the shade. And Theo wasn’t the only player who went down with heat illness that day.

The problem was not only the weather. These kids were playing on artificial turf. It absorbs more heat from the sun than grass does and has no natural way to cool off. So, the “feels like” temperature on the turf during that day’s game was 53 °C (127 °F), medics told Theo’s parents. U.S. Youth Soccer rules say to use the overall air temperature to determine how safe it is for kids to play. And that temperature was not as high. According to the rules, the heat was severe enough to give players extra water breaks. It just wasn’t bad enough to cancel the game.

Many youth-sports groups do not even have rules to protect players from high heat. Plus, some coaches and parents don’t want to cancel or change games or practices. And kids may not want to admit when they need a break, for fear of seeming weak or letting down their team.

That can put young athletes in a dangerous spot. In the United States alone, heat sickens more than 9,000 high-school athletes each year. Better awareness among players, coaches and parents about heat’s dangers could lead to better protections. Luckily, there are some simple strategies that both athletes and sports organizations can use to ward off heat illness.

Such protections will prove ever more important as climate change turns up the heat.

How hot is too hot?

Scientists use a measure called the “wet bulb globe temperature,” or WBGT, to rate temperature safety. WBGT takes into account air temperature, humidity, wind speeds and the amount of heat from sunlight. Combining all these factors gives a better sense of how dangerous the weather is than air temperature alone. That’s because it’s harder for the body to cool itself without a breeze or in high humidity at any temperature.

An air temperature of 30 °C (86 °F) with 30 percent humidity (pretty dry) amounts to a WBGT of 26.2 °C (79.2 °F). With 75 percent humidity, that same air temperature becomes a dangerous WBGT of 32 °C (89.6 °F). By a WBGT of 35 °C (95 °F), the human body can no longer cool itself, notes Sylvia Dee. She’s a climate scientist at Rice University in Houston, Texas. Under these conditions, someone can overheat and die.

Short of death, assessing the risk of different WBGTs can get complicated. One reason: The WBGT value often is not the only thing that matters. Someone can have a bad reaction to any temperature that’s a lot higher or lower than they’re used to. So, a fluke spring or fall heat wave — where the temperature jumps — could be dangerous, says William Adams. He’s a sports medicine scientist at the University of North Carolina Greensboro.

Geography matters, too. Say you’re in a northern state, such as Oregon or Minnesota. You might be accustomed to early summer temperatures around 21 °C (70 °F). A 35 °C (95 °F) day would be a shock to your body, says Susan Yeargin. The same heat may not bother someone from Arizona or Louisiana, where it’s much warmer year-round. Yeargin is an athletic trainer at the University of South Carolina in Columbia. She’s made a study of heat illness.

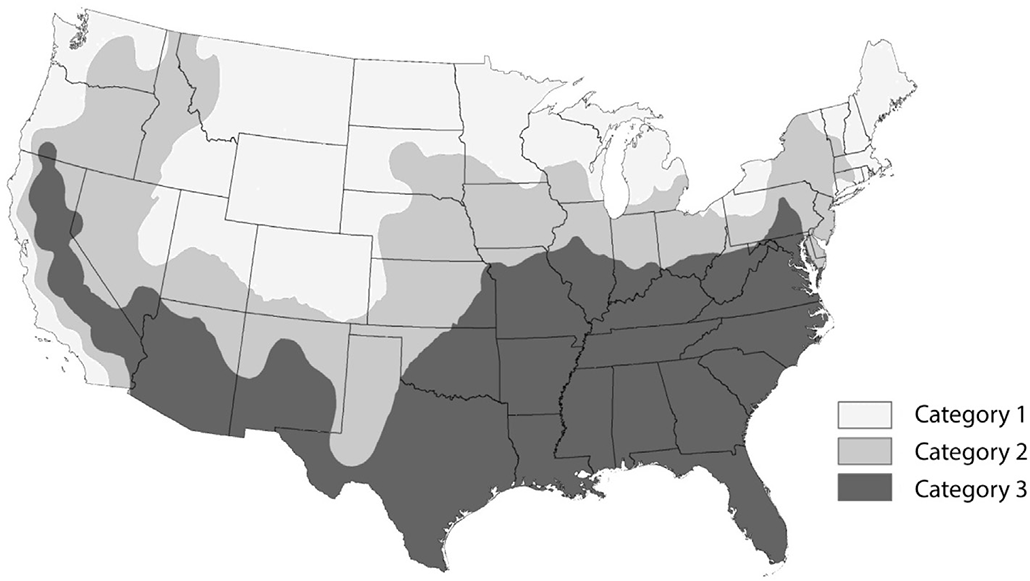

Regional climate differences are why WBGT guidelines for what counts as “dangerous” differ based on location, Yeargin says. The United States is divided into three categories, based on average temperatures. Cooler, drier Northern and Western states are category 1. Category 2 includes much of the Midwest and parts of the Northeast. Category 3, where summer heat is often extreme, includes the South, including Arizona and New Mexico.

Regional rule differences

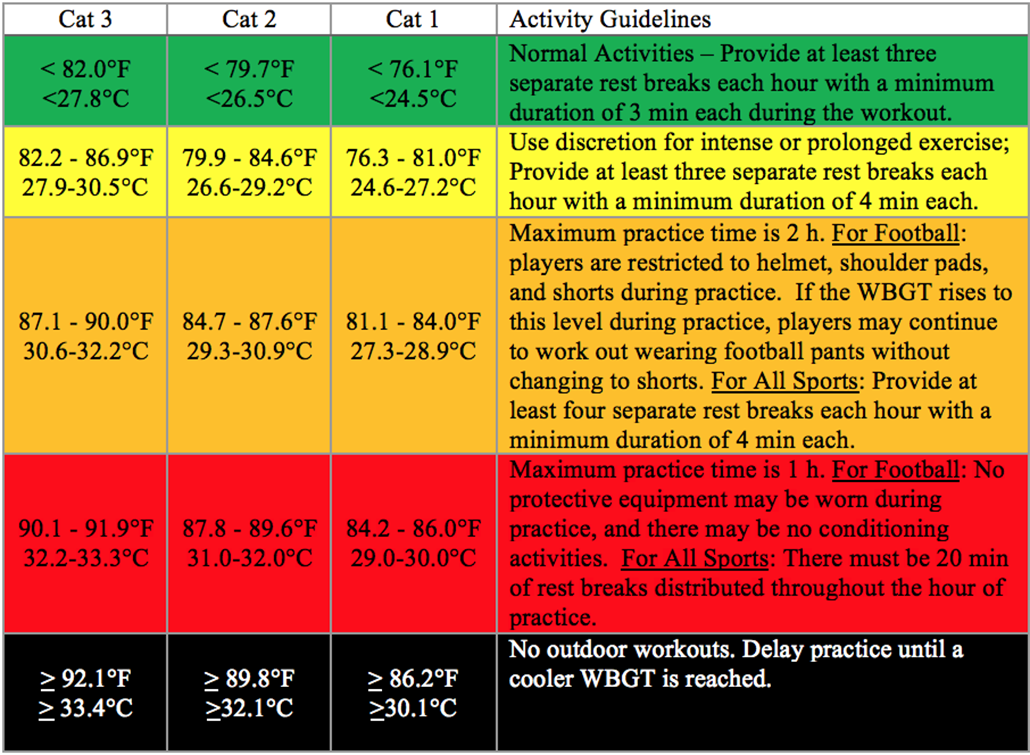

The United States is divvied up into three categories. Each category uses different wet bulb globe temperature (WBGT) cutoffs to determine youth-sports guidelines. For instance, in a category 1 state, such as Maine, a WBGT of 30.1º Celsius (86.2º Fahrenheit) would require canceling all outdoor workouts. But in a category 3 state like Florida, the same WBGT would only require giving players extra water breaks. The reason: People in warmer regions are expected to be more accustomed to warmer temperatures and/or higher humidity.

What to do?

Scientists have come up with recommendations for how sports organizations should respond to high WBGTs. Those recommendations include extra water breaks, longer breaks and shortened or canceled games or practices.

The WBGT threshold for each recommendation varies by region. For example, a WBGT of 30.1 °C (86.2 °F) would trigger cancelation of all outdoor workouts in category 1 locations, such as Oregon and Minnesota. But that temperature would hardly even trigger additional breaks in category 3 sites, such as Texas.

That regional difference likely contributed to Theo’s heat illness, his dad says. Theo is from Minnesota, which is in category 1. There, the temps experienced at the tournament would’ve caused games to be moved to early mornings or late evenings — or even be postponed. But Theo’s tournament took place in a category 3 city: St. Louis, Mo. So instead of canceling or changing the game times, U.S. Youth Soccer added extra water breaks, as per their rules.

This also points to why youth athletes who travel for tournaments need to be especially careful, Adams says. When they play in places that are warmer than they’re used to, they may be at higher risk of heat illness.

Impacts of overheating

When things heat up, the body’s first line of defense is to sweat. This moisture carries away heat as it evaporates off your skin. If you can’t sweat away the heat — say, because it’s too hot or humid outside — then your blood starts to heat up. Your body’s temperature will also rise. Your pulse can race as your heart works overtime, trying to pump blood through your body. This can make you ill.

Heat sickness symptoms

Signs of exertional heat illness can include:

- Muscle cramps

- Dizziness

- Headache

- Nausea

- Excessive sweating (or cold, clammy skin)

- Confusion

- Heart racing (fast pulse)

- Difficulty with coordination

- Passing out

Source: CDC

When someone gets sick from doing intense activity in warmer-than-usual or high temperatures, it’s called exertional heat sickness. Symptoms vary from muscle cramps and excessive sweating to heat exhaustion. That last condition can involve dizziness, nausea, confusion and passing out.

Heat stroke is the most severe type of heat illness. This can happen when the body’s core temperature exceeds 40 °C (104 °F). At that point, someone can pass out, have seizures — even die.

If you’re playing a sport and start to experience any of these symptoms, or even just feel extra hot, take a break immediately, experts say. Tell your coach or parents that you’re overheating. Sit in the shade. Dump water over your head. And drink fluids. Do not push through it, says Tamara Hew-Butler. She’s a sports scientist at Wayne State University in Detroit, Mich.

Some athletes face a greater risk of heat illness than others. Football has 10 to 11 times more heat illnesses than any other high-school sport. Reported heat illnesses happen about 4.5 times per 100,000 practices or games in high-school football. While that might not seem like a lot, those only include cases severe enough for an athlete to see a doctor and be kept from playing for more than a day. In fact, experts say, heat illnesses often go unreported.

Football also has the most deaths from heat stroke in youth sports — 68 between 1996 and 2021. Most were high-school athletes. That’s because football is an intense sport with a lot of exertion. It also starts in August. In the United States, that’s the hottest time of the year. These athletes also wear heavy protective equipment that makes it hard to keep cool.

Cross-country has the second most heat-related illnesses. But even kids who swim or play indoor sports can experience heat illness, Adams says. So can kids in marching bands or those playing outside during gym class or recess.

One study of U.S. marching bands, for example, found nearly 400 cases of exertional heat illness between 1990 and 2020. Nearly 90 percent of those happened in high-school musicians.

Luckily, there are ways to protect against dangerous overheating.

Prevention is the best medicine

Preventing exertional heat illness starts with hydration.

Water is key to controlling body temperature, Adams says. It helps you sweat. If you’re dehydrated, your body will hold onto the water it has rather than sweating it away. And that makes it harder to cool off and easier to get heat illness.

Water is the best thing to drink. But when your body sweats, you also lose salt, Hew-Butler points out. Salt helps the body stay hydrated. It also keeps minerals in your body balanced so that muscles and nerves can work properly. Electrolyte sports drinks, such as Gatorade, can help replace that key nutrient.

Schools, sports leagues and coaches can also help protect players when it’s hot by easing them into games and practices. It takes at least three days in a row of hot or warmer-than-usual temperatures for the body to start adapting, Yeargin says. Those adaptations include a lower heart rate while exercising, a lower core-body temperature and an increased sweat rate. The body also ups its blood plasma volume when it’s hot — by about 15 percent. “Plasma makes up the largest portion of whole blood. Because of the increase in plasma volume, the cardiovascular system can work more efficiently,” she says.

“It’s during those first three days, when our body makes no adaptations, that [youth athletes] are at highest risk for heat illness,” Yeargin adds. “It takes seven to 14 days for your body to make all those awesome adaptations” to better handle the heat. A lack of adaptation likely contributed to Theo’s heat illness during the tournament. He and his team had not experienced high summer temperatures yet that year.

Ramping up sports practices and games in warm weather faster than those seven to 14 days can be dangerous. Most heat-related deaths in youth football happen during the preseason — that first week or two of practice when kids are not used to exercising in the heat or are trying extra hard to make the team.

U.S. high-school football programs have 14-day adaptation plans so that athletes’ bodies can ease into working in the heat. For example, players don’t wear pads on the first two days. They can’t do more than one practice a day for the first five days. And practices have to be shorter with more breaks. Similar recommendations exist for some soccer and field-hockey programs and a few other sports.

Research has shown that such heat adaptation plans are effective. One 2016 study, for instance, looked at heat-related deaths during preseason high-school football practices. The researchers compared deaths from heat before and after some states had put heat-adaptation guidelines into practice. Heat-related deaths were 2.5 times greater in those states before they implemented guidelines, compared with after, data showed.

But most youth programs don’t have rules — or even recommendations — for easing into the season. Every athletic program should have heat safety rules for when to add more breaks, shorten athletic events or even cancel them, Yeargin says.

What to do if you overheat

Feeling too hot in the middle of a sports practice? Don’t push through it. Here’s what you can do to stay safe:

- Move to shade or air conditioning

- Hydrate with water or a sports drink

- Remove extra clothes or equipment

- Lie down with your legs above your head

- Pour cool water over your head or sit in a tub of cool water, use cooling rags or ice packs

- Seek medical attention

Source: CDC

Keeping cool in a warming world

Protections against heat illness are only growing more important as climate change warms global temps and triggers more temperature spikes, known as heat waves.

Temperatures have been rising across the United States. For instance, Minnesota summers now average 1.7 to 3.3 degrees C (3 to 6 degrees F) warmer than they were about 100 years ago. Summer temps there also last a month longer than they used to. Meanwhile, Austin, Texas — which already averages around 30 days a year above 38 °C (100 °F) — is expected to have almost twice as many days that hot within the next 15 or so years.

In many parts of the United States, WBGTs are projected to increase beyond safe levels for outdoor sports by the mid to late part of this century, notes Dee at Rice University. That will require radically rethinking when, where and how long it’s safe for kids to play.

“The planet is getting hotter,” agrees Hew-Butler at Wayne State in Michigan. “We need to start addressing how we’re going to cope with that.”

Groups like the National Athletic Trainers’ Association and the Korey Stringer Institute have offered some suggestions. (Named for a football player who died from exertional heat stroke, the Korey Stringer Institute provides education and outreach to prevent heat illness and death in athletes.) Sports organizations, schools, teams and coaches need to develop heat policies, they say, and monitor WBGTs so that they can make practice or game changes as needed. Those changes could include scheduling events when it’s cooler — earlier or later in the day — or moving inside to air-conditioned facilities. Practices could also be made less intense by skipping timed drills or adding more breaks. Coaches and referees also need to know the signs of heat illness and have cold water, ice packs or ice buckets at the ready.

“We need to be responsive and have backup plans for when the weather is not conducive to athletics or playing outside or playing sports,” Hew-Butler says.

In the meantime, it’s important for athletes to listen to their own bodies. They also need to speak up when they need breaks. During his tournament, Theo worried that leaving the game would let his coach or his team down. But in hindsight, he says, he should’ve taken himself out sooner. It may be hard to put your health first during the heat of competition, or when you’re trying to make a team or even just having fun playing a game you love.

But ignoring the risk of heat sickness is dangerous. And it can be deadly.