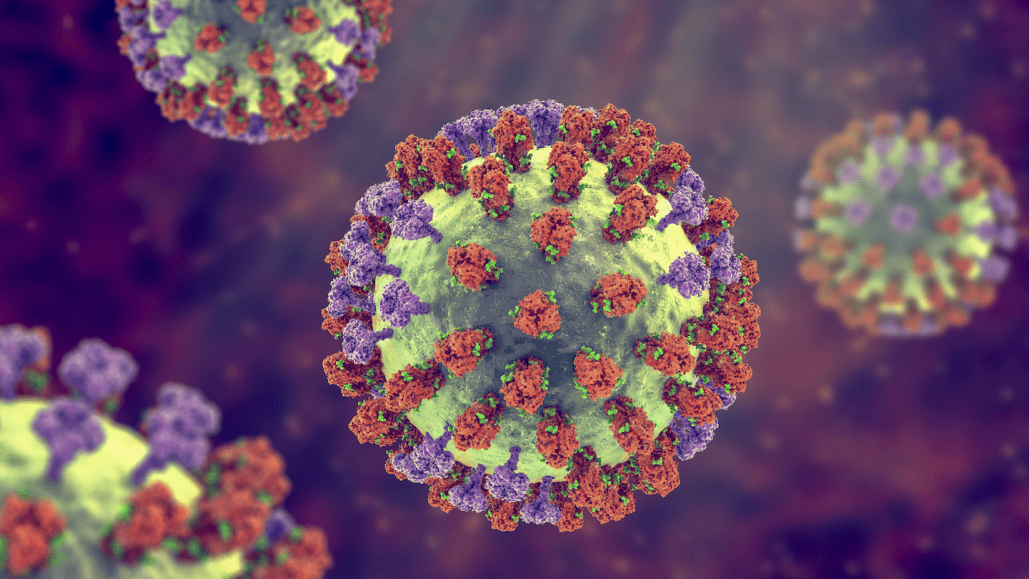

Viruses can cause a huge spread of illnesses — from deadly diseases to the common cold. Here’s how these devious germs work.

KATERYNA KON/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY/Getty Images

Share this:

- Share via email (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share to Google Classroom (Opens in new window) Google Classroom

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

Viruses are tiny hijackers.

These germs are simple microbes. Each one is just a set of genetic instructions — either DNA or RNA — inside a protein pouch. Unlike living cells, like those found in a person, viruses don’t have the tools to reproduce. So to make copies of itself, a virus must infect something else.

That “something else” might be an animal, plant or even bacterial cell. Once inside, a virus will use its host cell’s machinery to copy its genetic code and build more versions of itself. These newly spawned viruses then go off to infect other cells. This process often kills the host cells — which is why a viral infection can make you sick.

The Cleveland Clinic offers a great analogy for how this works: “It’s like someone breaking into your house to use your kitchen. The virus brought its own recipe, but it needs to use your dishes, measuring cups, mixer and oven to make it. (Unfortunately, they usually leave a big mess when you finally kick them out.)”

Viruses cause a huge range of illnesses. Some, like the common cold, aren’t that bad. Others can be quite serious. Polio, Zika, dengue fever, measles, COVID-19 and the flu are just a few examples of viral diseases. Unlike bacteria, viruses can’t be wiped out with antibiotics. But vaccines can help protect you and your pets from dangerous viral infections.

Winter is prime time for some airborne viruses to spread, including the flu, COVID-19 and the common cold. That’s partly because some viruses thrive in dry wintry air. Another factor is that in winter people spend a lot of time inside, where they can more easily catch infections from each other.

To protect yourself from viral hijackers, consider using a humidifier or air filter. And if you’re feeling under the weather — or around someone who is — consider masking up.

Want to know more? We’ve got some stories to get you started:

AI can now write working genetic instruction books from scratch Two AI models designed these genomes for viruses that kill E. coli bacteria. They’re the first functioning full sets of DNA ever designed by machines. (12/22/2025) Readability: 7.1

2025’s Texas measles outbreak is a lesson in the value of vaccines The outbreak shows that a near absence of once-common childhood diseases — like measles — is not evidence that vaccines are unnecessary. (3/20/2025) Readability: 7.7

Want to avoid getting sick? Adopt these immune-boosting behavior Research points to ways we can work to stay healthy, even in the face of germs. (9/5/2024) Readability: 7.3

Explore more

Explainer: Virus variants and strains

Explainer: Why it’s easier to get sick in the winter

Lasers can eavesdrop on microbes, including viruses

Electric shocks act like vaccines to protect plants from viruses

Teen finds cheaper way to make drugs against killer viruses

In 2024, bird flu posed big risks — and to far more than birds

Explainer: What is mpox (formerly monkeypox)?

Infected caterpillars become zombies that climb to their deaths

Are viruses alive, not alive or something in between? And why does it matter? (from Science News)

Activities

Viruses are super, duper tiny. Much tinier than the cells in your body. So tiny, in fact, that an estimated 500 million rhinovirus germs — which cause the common cold — could fit on the head of a pin. That may be hard to picture. But this activity from Science Buddies can help you wrap your brain around just how extremely small viruses are.