Fast, mysterious clouds swarm around our galaxy

The Milky Way’s forecast: mostly cloudy. But the origin of these cosmic clouds is unclear

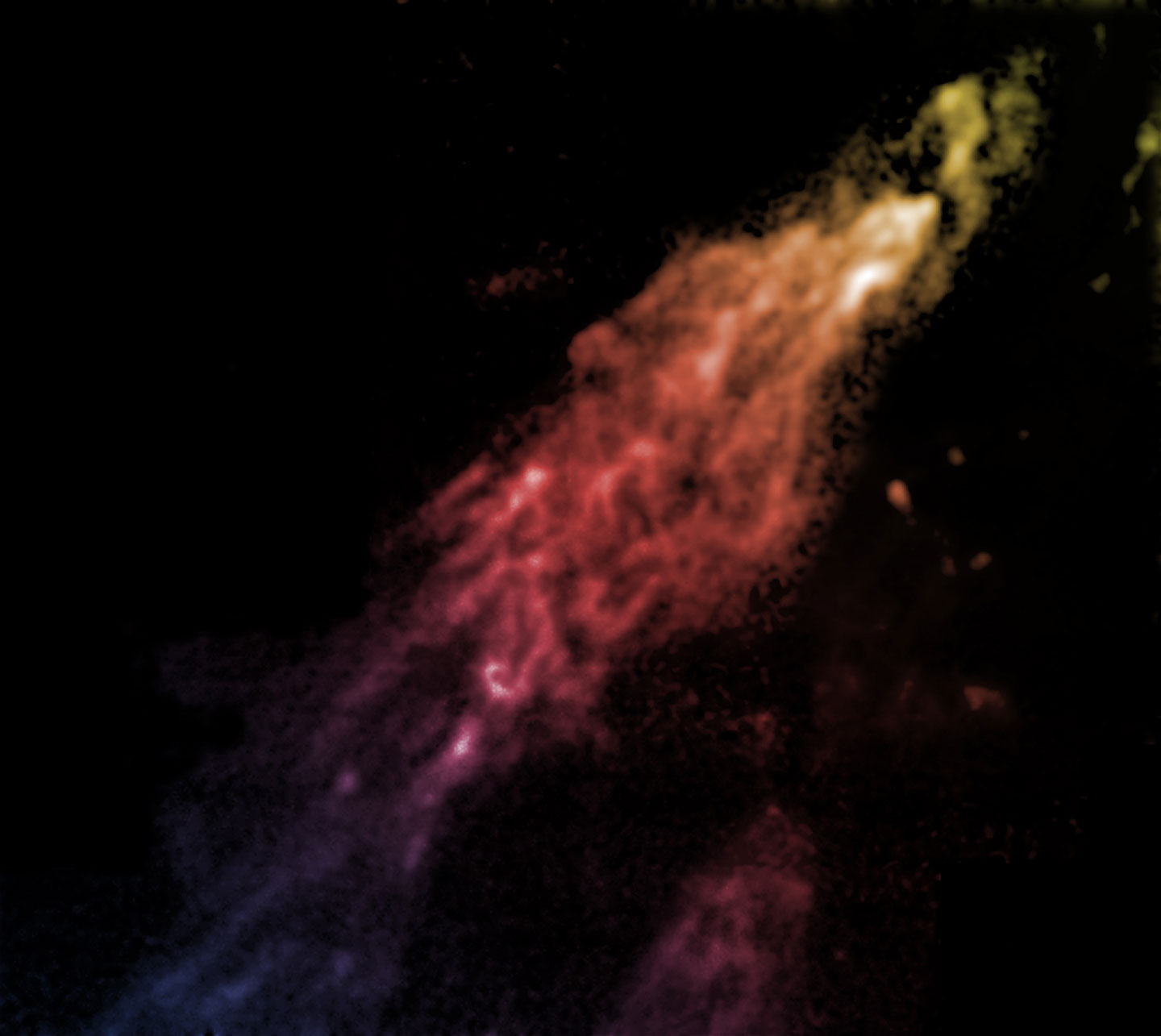

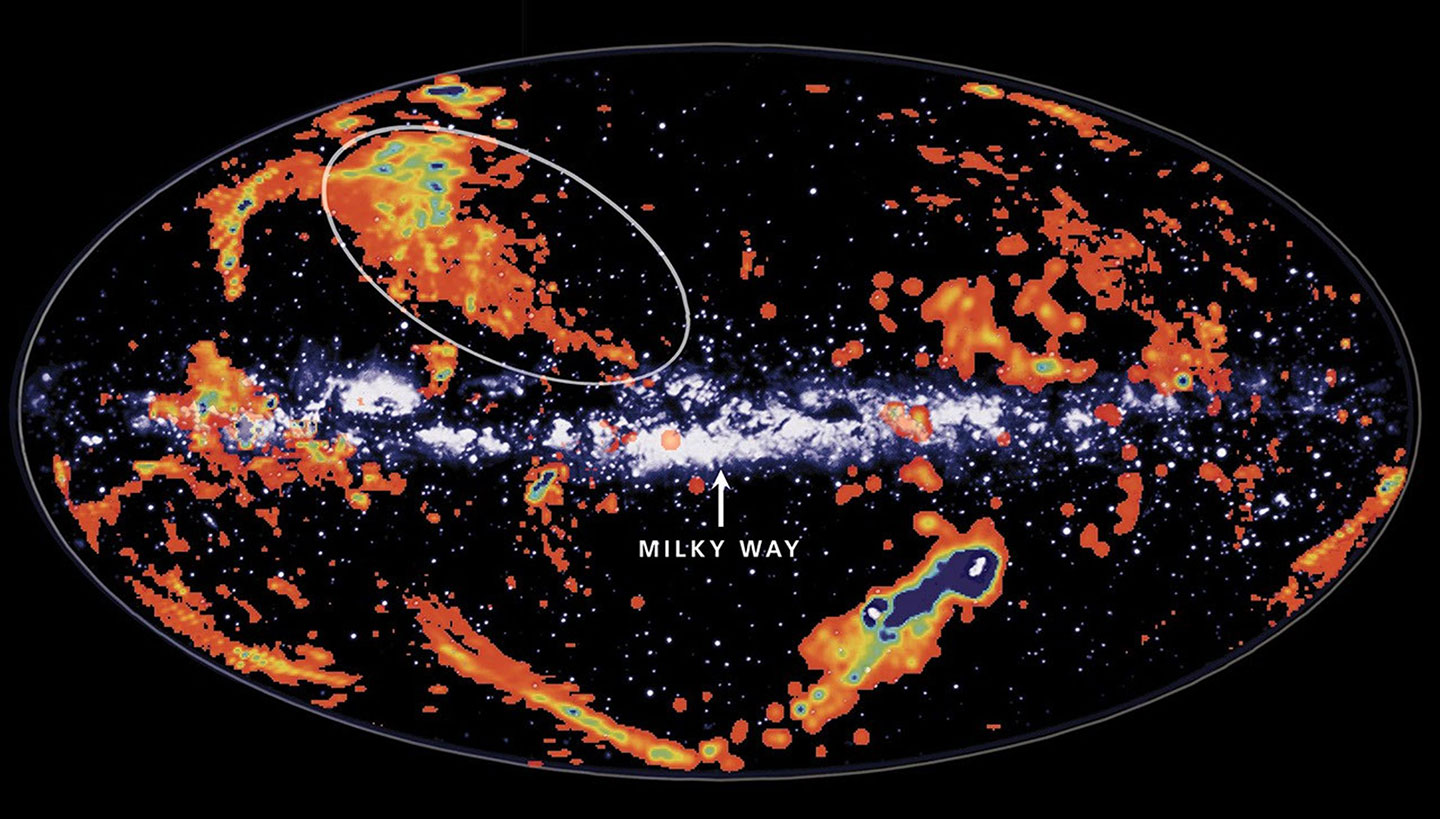

This composite image shows Smith’s Cloud (reddish, left of center) moving toward the Milky Way. (The image of the Milky Way is a false-color photograph where different colors correspond to radio signals.) One 2016 study found that some 5 million years ago a similar cosmic cloud may have punched a hole in the Milky Way’s disk.

NASA/ESA/Levay/STScI, Saxton/Lockman/NRAO/AUI/NSF/Mellinger

Share this:

- Share via email (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share to Google Classroom (Opens in new window) Google Classroom

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

Beyond the bright swirling arms of our Milky Way galaxy, something enormous, mysterious and shadowy barrels toward us. It’s called Smith’s Cloud. And it isn’t like any cloud you’ve seen before.

From head to tail, it extends more than 11,000 light-years. That’s roughly 2,500 times the distance from the sun to its closest stellar neighbor.

And Smith’s Cloud is fast. It covers 300 kilometers (nearly 200 miles) every second. That would be fast enough to zoom from Earth to the moon and back in less than an hour.

Instead of ice or water vapor, Smith’s Cloud is a cold gas made mostly of hydrogen.

Most peculiar, though, is where it’s going. Smith’s Cloud doesn’t move in the same direction, or at the same speed, as the stars that make up our galaxy.

The Milky Way is flat and spins like a record on a turntable. Smith’s Cloud is outside it. This cloud moves more like a giant pencil diving into that disk from above. Imagine if Earth’s clouds behaved like this: Sometimes you might look up and see a cloud that didn’t drift across the sky but instead plummeted toward the ground.

Indeed, one day — in 27 million years or so — Smith’s Cloud is destined for a spectacular collision with the Milky Way that could produce new stars.

Smith’s is what astronomers call a “high-velocity cloud,” or HVC. It’s not the only one. In fact, our galactic forecast seems mostly cloudy.

Some studies estimate that HVCs cover more than 60 percent of the sky. They’re invisible to the human eye, day and night. But they can be seen and studied with telescopes.

Most appear to be streaming inward, toward our galaxy. But because they’re so far away, it’s hard to be sure. Some HVCs may be on their way out.

Astronomers found the first HVC more than 60 years ago. Ever since, they’ve been puzzling over how these clouds form, what they’re hiding and their connection to galaxy formation.

It’s a worthwhile effort. HVCs may offer an important piece of the whole cosmic story. To astrophysicist Naomi McClure-Griffiths, what might be most exciting about HVCs is that they’ve inspired astronomers to think in new ways about how galaxies form and change. McClure-Griffiths works at Australian National University in Canberra. She’s also the chief scientist for the SKA Observatory, a global network of radio telescopes.

These eyes on the skies may help answer big questions about HVCs.

Where do they come from?

Even after decades of research, “we don’t know exactly how are these high-velocity clouds made,” says Snežana Stanimirović. An astronomer, she works at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. There, she searches the cosmos for material that resides outside galaxies, like HVCs.

“They’re still mysterious,” she says of HVCs. That’s one thing that makes them interesting to her. They appear to play a role in how galaxies form and morph.

Early on, some scientists had suggested HVCs were made of remnant material left nearby after the Milky Way formed. Gravity, they thought, might now be pulling those leftovers back in. Other researchers wondered whether the clouds had once blasted out of our galaxy and were now falling back in. Some scientists have even proposed that the clouds were stuff that had been stripped away from smaller galaxies — ones that had long ago bumped up against the Milky Way.

What is clear, Stanimirović says, is that HVCs can’t be explained by a single source. They’re more complicated than that.

These clouds “don’t have a single origin,” agrees Nicolas Lehner. “They have multiple origins.” An astronomer, Lehner studies HVCs at University of Notre Dame in Indiana.

Cloud watching

Astronomers spied the first signs of HVCs with radio telescopes. These instruments detect energy emitted by distant objects in space. (Using radio waves, scientists can study properties they can’t see with visible light or other telescopes.)

Every element absorbs and emits its own distinct pattern of radio waves. By studying these signals, astronomers have been able to identify the chemical makeup of cosmic objects — from galaxies and gas clouds to supernovas. (Of all the types of electromagnetic radiation, radio waves have the lowest energy.)

Back in the 1950s, scientists were using radio telescopes to study clouds of gas between stars. But in 1956, those sky studies revealed something else. Radio “noise” hinted that dense clumps of gas might be lurking outside the Milky Way. That gas might make a giant sphere surrounding the galaxy’s disk.

Could that gas condense into clouds? A few scientists began searching for them.

In September 1963, that search turned up a cloud unlike any seen inside the galaxy. It wasn’t moving with the rotation of the Milky Way. Instead, it was barreling toward the disk at an estimated 175 kilometers per second (110 miles per second).

This was the first HVC ever detected.

Two more HVCs turned up the same year. All three were made of neutral hydrogen, with other elements sprinkled in. (Neutral simply means the hydrogen had no electric charge.) Seeing hydrogen wasn’t surprising. It’s the most common element in the universe. The other elements present could offer clues to where HVCs are born.

One of those HVCs was Smith’s Cloud. It was named for its discoverer, astronomer Gail Smith. At the time, she was a graduate student at Leiden University, in the Netherlands. Smith’s Cloud is now the most-studied and best-known HVC.

Galactic fountains

Since then, astronomers have observed more HVCs scattered across the heavens. They can be found all over the sky. They’ve also inspired many, many questions, such as: “Are these intruders? Are they coming from some other galaxies?” Stanimirović asks. Or are they objects that once lived in the Milky Way disk and, at some point, got expelled?

That last idea was one of the first ones proposed.

Dutch astronomer Jan Oort helped find and study the first HVC. He would go on to hypothesize in the 1960s that HVCs formed from gas left over from when the Milky Way formed. That would have been billions of years ago.

Others have since suggested that ancient high-energy events blasted vast clumps of gas out of our galaxy. Maybe a bunch of stars, for instance, “went supernova at about the similar time,” says Stanimirović.

That huge burst of energy would have blown gases outward. Once those dying stars ran out of fuel, the exiting gas plume would slow and cool, condensing into clouds. Over time, they could change shape and direction. Eventually, our galaxy’s gravity would begin to tug them back toward its disk. (Imagine a volcano blasting lava into the sky. As that molten lava cooled in the air, it would solidify into rocks that fell back to Earth.)

You might think of these as “galactic fountains,” Stanimirović says. Maybe the Milky Way produced many HVCs this way. As those speed demons fell back toward the galaxy, they could serve as new star-making material.

Some astronomers even call HVCs a “galactic fuel supply.” They argue HVCs may be some of the largest recyclers of matter in the known universe.

If this idea is true, HVCs should contain metals and dust, says Lehner. That’s because galactic fountains are driven by stars, and stars are where metals are born. Any gas they shoot out, therefore, should also contain metals.

Such dust would be “an ingredient that tells you the HVC is probably coming from the Milky Way disk, instead of [from] outside,” he says. “The dust has to come from somewhere.”

For decades, Lehner says, studies of HVCs turned up no dust. But by the end of the 20th century, better telescopes started to spy it.

In the last decade, astronomers have found metals in Smith’s Cloud, for instance. Some of those measurements came from the Hubble Space Telescope. Smith’s metal content suggests it might have formed from a galactic fountain, blown out of the Milky Way millions of years ago.

But the details aren’t clear. So the debate isn’t settled.

Scientists still can’t explain the incredible size and speed of Smith’s Cloud. It contains as much mass as a few million suns. That means it would have taken an enormous amount of energy to produce — more than scientists can explain from a galactic fountain.

Some astronomers have argued instead that this HVC may be the remnant of a dwarf galaxy that passed too close to the Milky Way.

Smaller HVCs, says Stanimirović, are easier to explain as galactic fountains. The big ones may be something else, she says — like the sign of a smaller galaxy punching through our cosmic neighborhood.

Even without understanding Smith’s Cloud, though, astronomers have made headway in measuring HVCs.

One 2019 project by Lehner and others, for instance, analyzed studies of HVCs to understand how they seem to have interacted with the Milky Way. Right now, it suggests, more gas seems to be flowing into the galaxy than out of it. But it spotted clouds moving in both directions — almost as though the galaxy is breathing. These data support the idea of galactic fountains being one source of HVCs.

Peeled-off material

Even if condensing gas and galactic fountains are involved in producing HVCs, they can’t explain everything, says McClure-Griffiths, in Australia.

In the early 1970s, scientists discovered similar clouds near other galaxies. McClure-Griffiths has been studying one of those. It’s called the Magellanic (Maaj-eh-LAN-ik) Stream. “It is like the most phenomenal HVC,” she says. It has a “huge tail of material that extends like halfway across the sky. It’s enormous!”

The Magellanic Stream extends out from the Magellanic Clouds. They’re a pair of dwarf galaxies that orbit the Milky Way. (The terminology is confusing, admits McClure-Griffiths. The Magellanic “Clouds” are actually galaxies, while the Magellanic Stream is in fact a cloud.)

Unlike other HVCs, she says, “we know exactly where [the Magellanic Stream] came from.” And it’s not from leftover Milky Way debris or a galactic fountain. “It’s gas that’s been pulled off the Magellanic Clouds as they’re interacting with our galaxy.”

She’s using telescopes to study whether the gas in this HVC is also magnetic. “Magnetic fields [would] act like shields that keep the gas together,” she says. Maybe magnetic fields prevent the force of gravity from ripping them apart. That could explain why the clouds hold their shape.

Do you have a science question? We can help!

Submit your question here, and we might answer it an upcoming issue of Science News Explores

The dark universe

Astronomers are using HVCs to probe other big cosmic questions, too. These include studies of potential dark galaxies. That would be a big clump of gas that has no glowing stars — hence the name dark.

Over the last 20 years, studies have turned up a few possible dark galaxies. Astronomers suspect they’d be held together by dark matter. It’s a type of material that can’t be seen but still pulls on nearby objects through gravity.

In April 2025, astronomers in China reported that hidden within an HVC known as AC-I is a clump of gas. That gas rotates like a galaxy, but contains no stars. It may have hundreds of millions of times as much mass as the sun.

Now, scientists are looking for ways to better measure the distance to AC-I. That distance will help tell them how big it is. (A small, nearby HVC can look similar to a larger one that’s farther away.) Knowing the size of an HVC offers clues about how much material it has — and how a dark galaxy might be hiding inside it.

Measuring distances to HVCs is a well-known challenge, says Stanimirović. That’s because they don’t glow and have a very low density. To determine distances, astronomers search for some stars that are closer and other stars that are farther away. Then they sort of split the difference between those to make their estimates.

To study the possible dark galaxy inside AC-I, astronomers in China used a telescope called FAST. (That’s short for Five-hundred-meter Aperture Spherical Telescope.) FAST looks like a satellite dish sitting on the ground. And it’s big — as wide as the length of five soccer fields. “It’s an amazing telescope with great capabilities,” says McClure-Griffiths.

“Ears” on the cosmos

Powerful radio telescopes like FAST will continue to answer questions about HVCs.

Other such instruments that “listen” for radio signals from space are coming online soon. In a desert in Australia, for instance, engineers are building vast fields of radio antennas that look like metal Christmas trees. These are part of the SKA (short for Square Kilometer Array). It’s where McClure-Griffiths works.

The first SKA antennas started collecting data in 2024. Ultimately, the array will include more than 130,000 antennas!

The SKA team is also building an enormous array of 197 radio telescopes on the other side of world, in South Africa. These look like giant satellite dishes and will scan the skies at higher frequencies than the ones in Australia.

These two arrays will work together as one giant, global telescope. When done, SKA will be the largest and most powerful radio telescope ever built.

Since the discovery of HVCs, ideas about how they form and move have changed, says McClure-Griffiths. So have ideas about galaxies and even how the entire universe evolved. Some ideas get disproved. Others go away only to later come back.

“I think that’s what’s lovely about science,” McClure-Griffiths says. “People put out theories, and nobody finds any evidence. The theory becomes out of favor — and then you get a bit of evidence.” Suddenly, this “opens people’s minds again,” she says. “That’s quite beautiful.”