Fractals describe patterns hidden all around us

First named in 1975, these irregular shapes forever changed math and science

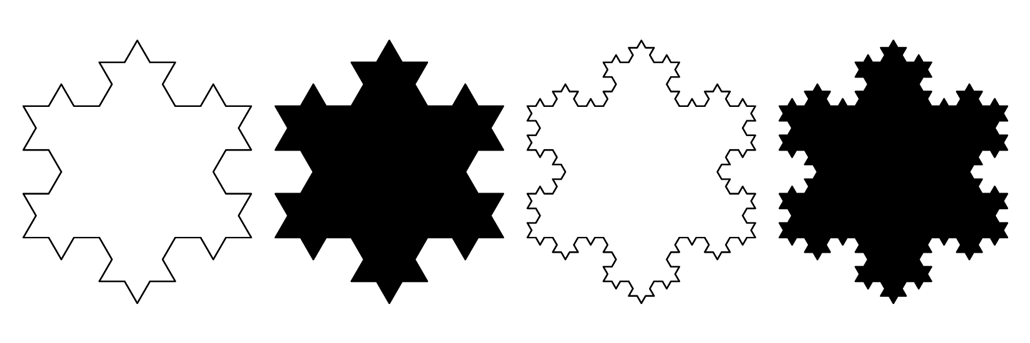

The outermost shapes here almost look like seahorses. If you zoom in on them, you’ll see more, smaller seahorses. Zoom in on those, and you’ll find even more seahorses. It’s seahorses all the way down. A shape where the same pattern repeats no matter how close you get is called a fractal.

Michael Piepgras/iStock/Getty Images Plus

Share this:

- Share via email (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share to Google Classroom (Opens in new window) Google Classroom

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

Imagine a tree. Moving up from the ground, the trunk splits into branches. Follow each of those branches, and they divide into smaller and smaller branches. Each of those in turn splits into twigs, then tinier twiglets. But even as the parts of the tree get smaller, the branches and their splits follow a similar pattern.

Or picture clouds. They have big fluffy shapes and tiny fluffy shapes, with rough edges. No matter how close up or far away you get, you see the same shapes. This idea of a pattern that repeats across many scales is common in nature. They’re in the environment, our bodies and even the grocery store. Blood vessels and mountain ridgelines show these types of patterns. So do clusters of galaxies in the cosmos.

Scientists, mathematicians and even artists have long used and studied these types of self-repeating patterns. Fifty years ago, the shapes got a name: fractals.

That name came from Polish-French-American mathematician Benoit B. Mandelbrot. He coined the term in a 1975 book. In it, he used the word to describe a family of rough, fragmented shapes that fall outside the boundaries of usual geometry.

Mathematicians had been describing these types of shapes since the late 1800s. But by giving them a name, Mandelbrot gave fractals value. He introduced a way to measure and analyze them. The name — from fractus, Latin for “broken” — helped recognize order in complexity.

Fractals’ hallmark trait is self-similarity. This means that no matter how much you zoom in or out, you find similar patterns.

Take a snowflake. The way that tendrils point out from the center is repeated at smaller and smaller scales as the snowflake branches out. (Mathematicians say snowflakes and other natural forms are “fractal-like.” That’s because the pattern breaks down at the level of molecules and atoms. A true fractal repeats to infinitely small scales.)

Fractals can take many forms. They can have rough lines, jagged shapes or complex curves. They stand out for defying our usual idea of dimension. Typically, an object’s dimension refers to the smallest number of coordinates needed to specify any point within it. A line is one-dimensional. Only a single value is needed to define any given point on the line. Area, like inside a circle, is two-dimensional. Volume, such as that inside a sphere, is three-dimensional, or 3-D.

Fractals don’t fit neatly in these categories. Instead, Mandelbrot introduced a mathematical definition for fractal dimension. It characterizes the roughness of a curve area or other shape. A fractal shape known as the Koch Snowflake, for instance, has a fractal dimension of about 1.2619. It’s somewhere between a line and an area.

A fractal world

Fractal-like patterns are everywhere. They bask on the edges of clouds and the craggy ridges on mountains. Mandelbrot saw them all over. He also observed that ordinary geometric shapes didn’t fit on these natural irregularities. “Clouds are not spheres, mountains are not cones, coastlines are not circles,” Mandelbrot once wrote.

Fractal-like structures show up in the body, too. Nerve cells and blood vessels branch to spread out and reach all parts of our body. “If you don’t have a fractal network of blood vessels, we would probably die every second, every time our heart beats, because it’s a very powerful pump,” says Michel Lapidus. He’s a mathematician at the University of California, Riverside. A branching structure, he says, gets the blood where it needs to go.

Fractal-like forms also appear in cancer cells and in airways in the lungs.

In the last 50 years, fractals have led to new kinds of math. Now there’s fractal calculus and fractal algebra. But fractals are more than just a subfield of math. Their characteristic roughness helps scientists visualize chaos. They can model the evolution of changing systems. They help engineers find new designs for practical gizmos. They even inspire artists and musicians.

In the world of mathematics, Lapidus has connected fractals with a field called number theory. He and others have used fractals to analyze how prime numbers are spread along the number line. A related puzzle, the Riemann hypothesis, is widely regarded as the most important unsolved problem in all of mathematics. An underlying fractal structure may one day figure into its proof.

Fractal finder

In a nod to fractals’ repeating patterns, Mandelbrot often told people that his middle initial, B., stood for “Benoit B. Mandelbrot.” So his full name becomes “Benoit Benoit B. Mandelbrot Mandelbrot.” And spelling out the middle initial again results in “Benoit Benoit Benoit B. Mandelbrot Mandelbrot Mandelbrot.” No matter how often you repeat, you find him behind his middle initial.

Beautiful and practical

Fractals also permeate society. They might help model the chaotic behavior of financial markets, Mandelbrot and others have thought. (That’s yet to be proved, though.) Researchers have measured the fractal dimension of the drip patterns in paintings by the artist Jackson Pollock. Even some music written by Johann Sebastian Bach contains fractal-like self-similarity. Combinations of long and short notes repeat at larger scales, in longer and shorter phrases.

Some mesmerizing fractal patterns might be considered art in their own right. But they can also lead to practical innovations, says Michael Barnsley. “It begins with, ‘Oh, that’s really interesting that you could make these complicated pictures,’” he says. “But mathematicians get drawn in, far beyond the pictures.”

Barnsley is a mathematician at the Australian National University in Canberra. He began looking closely at fractals in the 1980s. It started because he was interested in chaos theory. That’s the study of how random processes evolve from simple, set starting points. He noticed that images often include self-similar details. For instance, the way a line crosses a pixel in one part of an image might look the same as in another pixel.

That observation inspired him to design a strategy to compress the size of image files. By the early 1990s, Microsoft began using this method.

Fractal-inspired designs have also been explored for signal processing and data analysis. Fractal-like antennas full of curves can fit into small spaces and communicate over multiple frequencies.

Fractals may even prove vital to artificial intelligence (AI). Barnsley suspects that as AI companies race to improve algorithms and architectures, they will see potential in fractal-like design.

“Our brain is pretty much a fractal-like object,” he says. Connections between neurons are like a self-similar branching system. So a similar template, he notes, may pave the way toward “an artificial consciousness.”