As winters warm, athletes must cope with harder snow and tricky ice

Artificial snow, ice arenas and warming lake ice are changing the nature of winter sports

Snowboarders and skiers have lost a week or more of slope access in many places as global warming has shortened snow seasons around the world.

simonkr/Vetta/Getty Images Plus

Sarah Cookler remembers the first time she saw a racecourse covered with just artificial snow. “It was in the Pyrenees mountains in France,” she recalls. “The snow run had grass on either side.”

Cookler was coaching Team USA at the International Ski Mountaineering Federation’s World Youth Cup. Ski mountaineering — also known as “skimo” — is a sprint up and down a snow-covered mountain.

It was March 2023, almost the end of ski season. The snow run was beat up and compacted. It was also a warm day during an unseasonably hot month worldwide. “Gosh, it was probably around 40 to 50 degrees Fahrenheit.” Cookler recalls. “The conditions were wet.”

Her team had never before competed on a warm, slick course.

Dry, yellow grass bordered the starting line. The team warmed up by stretching and running on it. Then they carried their skis over to the snow to get ready for the starting whistle.

This team trains in Utah’s Wasatch Mountains. Here, they enjoy winter’s high snowpack and months of powder snow. As such, Cookler says, “Our athletes are used to skiing cold, deep, dry snow.”

Artificial snow differs from the natural stuff. Her team had skied on artificial snow before, though nothing this slick. Cookler had coached the athletes on techniques for artificial snow. So as they kicked off, they had some idea of what was ahead.

As shorter winters limit opportunities to ski and snowboard in nature, more athletes have had to train and compete on artificial snow. Higher temperatures and shorter periods of safe ice on frozen ponds and lakes also make it riskier for ice athletes to enjoy their sports outdoors.

World-class athletes have been adapting their training to artificial snow and indoor ice arenas. What they’ve learned can offer the rest of us tips for enjoying these environments safely.

Beads versus flakes

The 2022 Winter Olympics in Beijing exclusively used artificial snow. Watch reruns online and you probably won’t notice it wasn’t the real thing. But those who skied on it say they could definitely tell.

“It’s got kind of a beige [color],” said Noah Molotch. Your eye can easily pick it out, says this snow hydrologist at the University of Colorado Boulder. “It’s not yellow snow! But it does have a slightly darker appearance.”

Molotch spends a lot of time snowboarding. He also studies mountain snowpack. The best way to understand how to play safely in artificial snow, he says, is to know its properties.

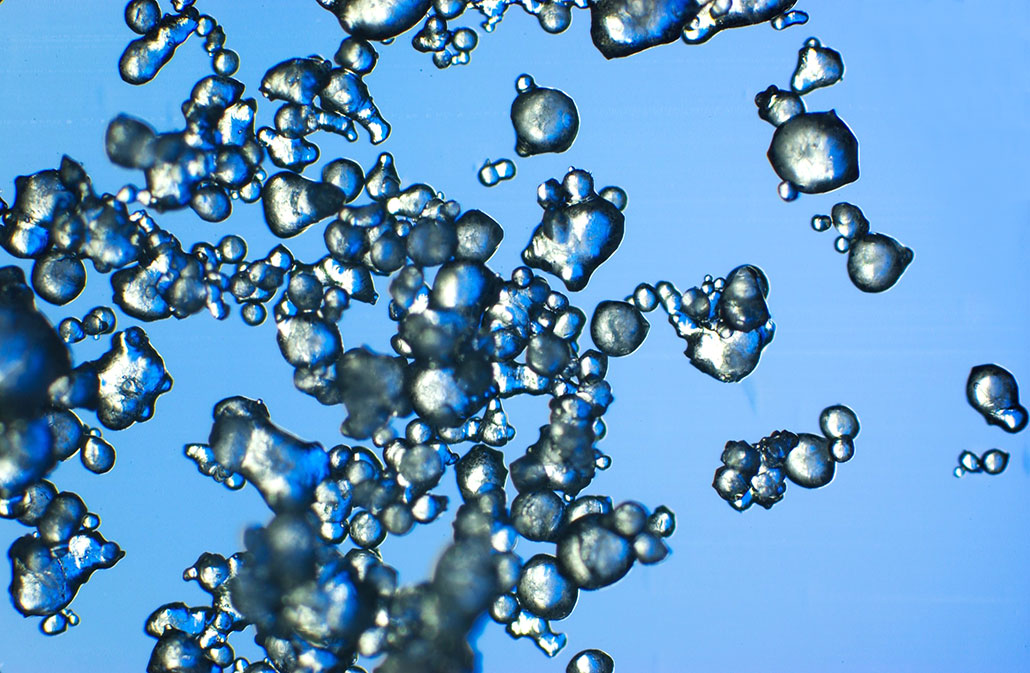

Under powerful microscopes, artificial snow looks nothing like real flakes. Its beady shape comes from the way it’s produced.

Machines start making these frozen bits when the air is at or below -2.5° Celsius (27.5° Fahrenheit). This is several degrees below the temperature at which water freezes — 0 °C (32 °F). High-pressure hoses use compressed air to spray water upward. This creates a fine mist. The tiny droplets quickly freeze into microbeads. Before they fall to the ground, powerful blowers propel them out onto the slopes.

“The beads are mixtures of ice and air, which is what snow is,” Molotch explains. “But those beads don’t have as much air as a natural snowflake.”

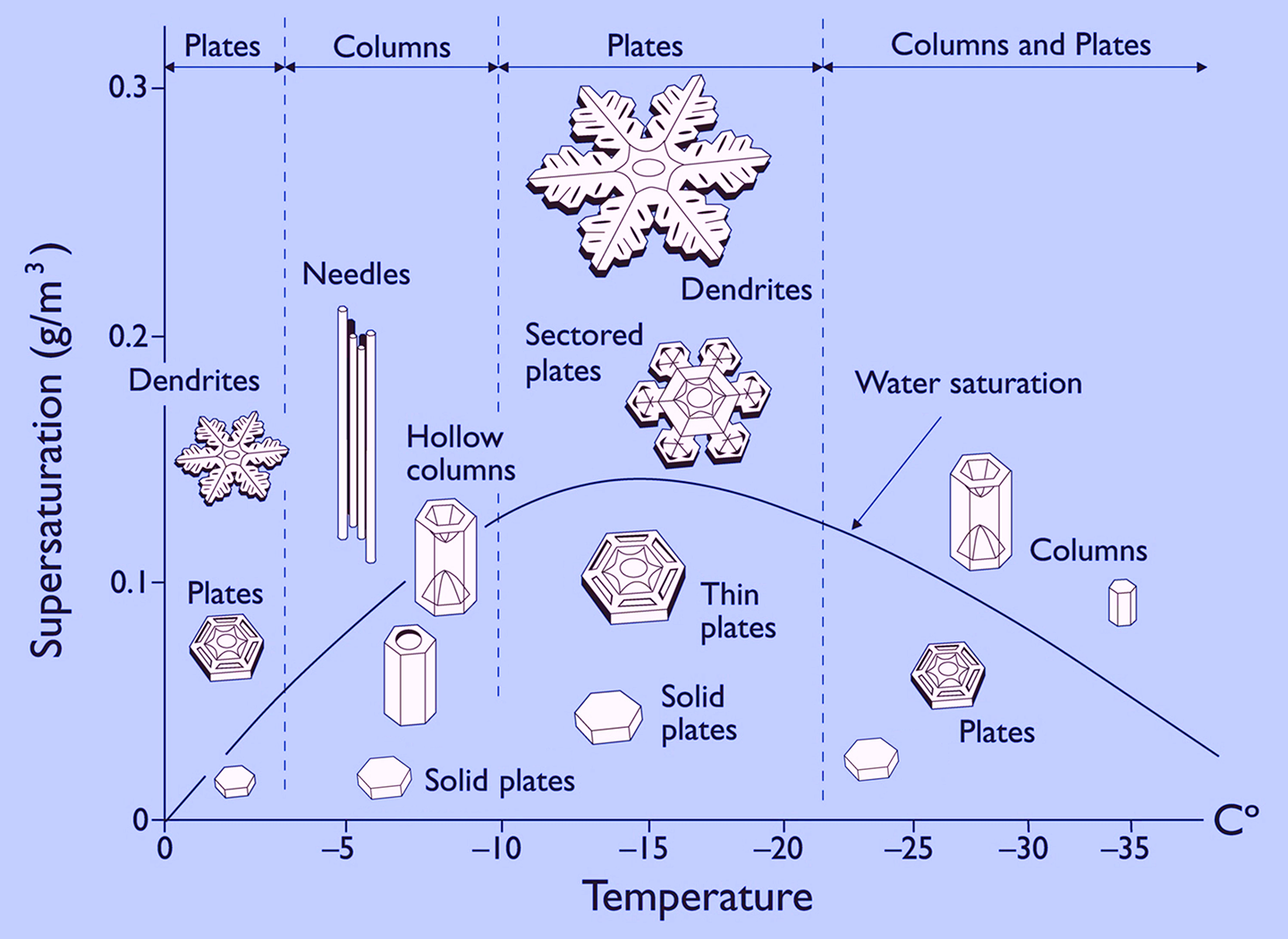

Unlike artificial snow, natural snow comes in many shapes — from simple needles, columns and plates to complex, stellar dendrites. Snowflakes start as ice crystals that form in winter clouds. At temperatures above -40 °C (-40 °F), ice crystals form around tiny particles, such as dust or even bacteria. At colder temps, water vapor can give rise to tiny crystals.

Different combinations of air temperature and humidity form flakes with different shapes and sizes. If the air is cold and dry, ice crystals tend to stay small and compact. In humid air, ice crystals develop rapidly. These form intricate, fern-like branches that clump into flakes. A huge dump of this kind of snow results in what’s called powder — the snow many skiers love.

Faster times

Powder snow is fluffy. That makes it a softer surface on which to fall. Higher temperatures can melt the surface, forming a stiff crust over the fluffy layered snow below. When more snow falls on top of these different layers, it creates an “irregular racecourse surface,” Molotch says.

“Artificial snow,” he notes, “is less likely to get rutted by skis.” Why? Its tiny beads bond together efficiently. That produces a firm surface that lasts longer than natural snow. “That cohesiveness is why it tends to resist the force of a ski driving the weight of an Olympic athlete on one edge,” he notes. Because artificial snow resists that force, its surface remains smoother. The result: Skis race across it faster and more efficiently.

Competitive athletes typically inspect racecourses the day before they compete. This lets them match their equipment to the conditions. For Cookler and her team, this meant tuning skis and choosing the right wax and skins.

To improve control and grip, athletes use a file to flatten a ski’s base and sharpen dull edges. They coat the bases with wax to help skis glide over the fluff. That wax can vary widely. Skiers try to match the right wax to conditions on the slope — such as whether it’s wet or dry, powdery or icy.

And artificial snow, Cookler points out, “rips the wax off a lot faster and is abrasive on the skis.”

“Wet snow can create a suction cup-like effect on skis,” Cookler notes. So for their Pyrenees trek, her team “chose a wax that had a hydrophobic effect.” It repels water. The team attached grippy climbing skins to their ski bases. These are fabric strips that provide traction (so skis won’t slide backward on uphill climbs).

Then they gauged what to wear for the race. “Artificial snow is usually colder than natural snow,” Cookler says. And its temperature “tends to change less because it’s compacted.” So for that warm spring day, her team wore its usual winter-race suits.

Race day is when technique and training matter. “Going downhill when snow is soft and slushy is going to be different than when it’s firm and icy,” Cookler observes. In slushy, artificial snow, Cookler advises being “a little softer with your turn so you don’t dig in as much.” Then you should be able “to ride a flat ski to keep up your speed.”

Do you have a science question? We can help!

Submit your question here, and we might answer it an upcoming issue of Science News Explores

Harder falls

But what athletes gain in speed in artificial snow, they pay for in harder falls, Cookler says. The reason: “There is no give in that snow.”

Still, teams need to train on this surface as much as possible in the lead-up to races. A warming climate has led to less predictable snowfalls. As a result, Cookler notes, today “artificial snow is prominent in all skiing events.”

It’s not a surprise that many ski resorts use snow machines. One December 2024 study by Climate Central found that winters in the Northern Hemisphere warmed measurably between 2014 and 2023. As a result, countries lost an average of seven winter days from December to February. These “lost” days were periods above freezing that should have been below freezing.

Europe, where there are the most ski resorts, lost more “winter” days compared to other regions — an average of at least two weeks per year.

Recreational skiers don’t always have to ski on the artificial white stuff. Some high-altitude resorts are in conditions cold enough that they never need to make snow. They just shorten their seasons. Other resorts use a mix of artificial and natural snow. They start making snow in the fall. It builds up a base reserve in case snow comes late in the winter — or not at all.

Molotch advises skiers and snowboarders to ask resorts where their artificial snow runs are. The reason: If you don’t spot a change in snow type, the new conditions could result in a crash.

“I have a lifetime of snowboarding. And at one point I had devoted my life to it,” Molotch says. “As a result, I have cartilage damage to some of my joints. And a lot of that has to do with impact on hard snow surfaces.”

Asked how he now adjusts his technique on artificial snow, Molotch says: “I ski away from it.”

Ice rink advantage

Competitive ice athletes aren’t experiencing as many changes as snow athletes are. That’s because their figure skating, ice hockey, speed skating and curling mostly take place in indoor ice arenas. However, ice quality can still vary greatly. Top athletes know how to read whether this is likely to slow them down or up their game.

“When you first step out there, you can tell if the ice is going to be hard or soft,” says Kelsey Koelzer. She’s head coach for women’s ice hockey at Arcadia University in Glenside, Pa. She feels soft ice makes her exert more effort to move. The cold, hard ice that’s perfect for hockey allows players to skate faster and with less effort.

In fact, she notes, “It impacts how quickly the game can be played, how quickly the puck is moving out on the ice and how fast goalies can move from side to side.”

Modern ice rinks and arenas produce different ice for different sports. Figure skaters need softer, warmer ice. It grips their skate blades better. Curlers prefer pebbled ice. It reduces surface friction and allows players to better control the trajectory and speed of the curling stone. And hockey players? They ask for a harder, colder surface — durable ice that’s built for speed.

Technicians alter the ice surface by controlling an arena’s ice temperature, humidity, air temperature and ice thickness. Purified water keeps the surface smooth. That surface is then built up layer by layer, by spraying a millimeter (four hundredths of an inch) of water with each pass.

Below the rink, a maze of pipes filled with coolant freezes each layer and keeps the rink frozen.

But indoor ice quality can still differ, even in regional and national games where arenas are supposed to follow standards.

“There is no consensus on what is optimal ice,” says Stefania Impellizzeri. A chemist, she works in Canada at Toronto Metropolitan University. She was part of a team that surveyed managers of North American ice arenas. Those arenas have no scientific way to accurately measure how they’re meeting the ice standards set by sports leagues, her team found.

It creates an unavoidable variation in ice quality. So teams have to account for this as they compete in different parts of the country, Koelzer says.

For instance, soft ice can affect how much game play will tire her athletes. “In warmer climates, it’s going to be harder to keep the ice as hard as in colder climates,” she notes. “The cooling units that keep the ice frozen have to work so much harder.” What’s more, when faster skaters head into a warm arena that has softer ice, they’re “not going to be able to play at the same speed that they would on colder ice.”

Lake ice is changing, too

Outdoor conditions present the biggest variable for ice athletes. While arenas are about ice consistency and competition, skating on frozen ponds and lakes is about having fun. But warming winters are making frozen ponds and lakes potentially unstable — and unsafe.

Lake ice has been forming later and breaking up earlier. That’s been shortening the period for safe ice cover, finds a team of researchers led by Joshua Culpepper. This hydrologist works at York University in Toronto, Canada. His team’s machine-learning computer model looked at data for ice thickness in Northern Hemisphere lakes going back to 1850. Then it projected how conditions might change through the end of this century.

Higher temperatures and changing ice quality will likely lead to between 8 and 19 more days of unsafe ice in early winter. Early melting will likely add 6 to 8 more unsafe ice days in late winter. The result: Globally, there could be 5 to 29 fewer days that lake ice will be safe to walk or skate on. The actual number will depend on how much warmer northern winters become.

Culpepper’s team shared its findings Dec. 11, 2024, in PLOS One.

Perhaps more troubling, how thick the ice is may no longer serve as a good sign of how safe it is. That’s the finding of a second study by Culpepper’s team in the September 2024 Nature Reviews Earth & Environment. Some U.S. states recommend that 10 centimeters (4 inches) of new, black ice is safe for people to walk on. But layers of white ice on top of black ice could make it unstable, this new study found — even when their total thickness adds up to 4 inches.

Black ice — also called clear ice or blue ice — forms in lakes during calm (wind-free), freezing conditions. “It’s structurally the most stable,” explains Culpepper. White ice develops when snow falls on top of black ice, melts, then refreezes.

“What we’re seeing and what we’re predicting is that climate change is contributing to more white-ice conditions,” said biologist Sapna Sharma. She, too, works at York University and was a coauthor on both studies.

“When you have more white ice [and] it’s close to 0 ºC, it’s about 50 percent weaker than black ice at the same temperature,” Culpepper says. “So, if you’re out on a lake that had a small layer of black ice and then it snowed a lot,” he says, “you need twice the recommended ice thickness” for it to be safe to walk or skate on.

Enjoy nature safely

It’s still possible to safely skate outdoors. It just may take a bit more care and caution than a century ago.

Angelina Huang is a retired Team USA figure skater and former gold medalist at the U.S. Nationals competition. “At an ice rink,” she notes, “you do laps in the same tiny area again and again.” She now feels freer skating on frozen lakes.

“It’s a lot less limiting,” she points out. “A lot of the lakes that I tend to skate on stretch 10 to 15 miles long.”

She makes it a priority to skate on safe, black ice. “I am confident in my training, and I train in self-rescue and ice knowledge every single year.” Less experienced skaters, she advises, need to find frozen ponds or lakes that are managed by safety experts. “That way [they] won’t let you on the ice until it’s safe.” And, she emphasizes, it’s important to never skate alone outdoors.

Culpepper agrees: Kids should always skate with an adult guardian and never at night. “Have an adult test the ice before going out,” he advises. “In small, shallow ponds it might not be as big of an issue. But if you’re thinking of playing hockey on a larger lake, then absolutely make sure you’re testing the ice to make sure it’s sufficiently thick.”

Sharma also urges that “if you’re going to go out on [lake] ice, learn how to swim in cold water.”

Koelzer hasn’t skated on a frozen pond or an outdoor rink in more than a decade. But she thinks “it’s certainly something a lot of players do for nostalgia and to just have fun.” “The big thing,” she advises, is enjoy skating in nature — but “always have your guard up.” In this warming world, snow and ice present new challenges: To chill out, you have to tune in to those changes.