A mosquito’s mouth can ‘print’ lines thinner than a human hair

Using this natural nozzle could make 3-D printing more accessible and sustainable

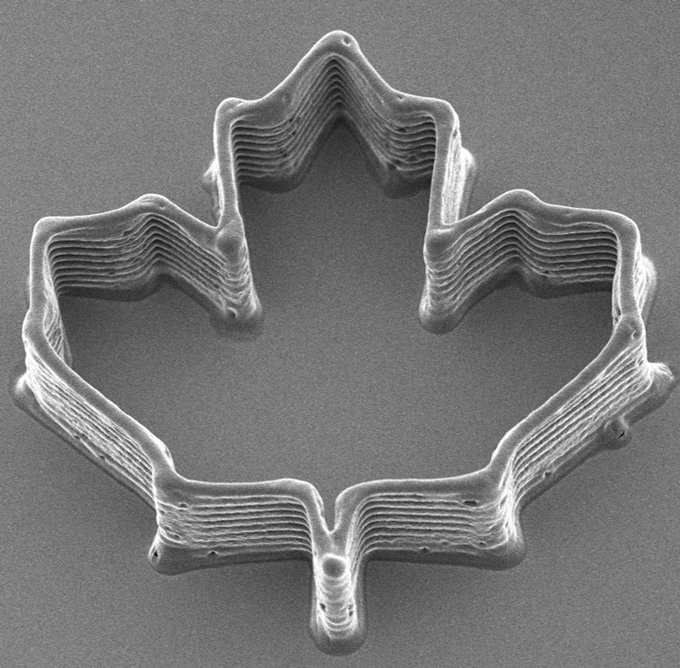

The proboscis of a mosquito (seen in this scanning electron microscope image of one insect’s head) is used for piercing skin. It’s also perfect for precision 3-D printing.

DENNIS KUNKEL MICROSCOPY/Science Source

Share this:

- Share via email (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share to Google Classroom (Opens in new window) Google Classroom

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

By Payal Dhar

A mosquito bite is really more of a poke. These insects use a long, needle-like mouthpart known as a proboscis (Prə-BOSS-sis) to pierce the skin. But this tiny straw could be good for more than just sucking blood. Its unique shape also makes it a great nozzle for fine 3-D printing, new research shows.

Engineer Changhong Cao led research into this at McGill University in Montreal, Canada. His team calls it “3-D necroprinting.” The term comes from necrobotics, the use of animal parts in machines. (Other engineers, for instance, have turned spider legs into grippers.)

By using the proboscis from a mosquito as a nozzle, Cao’s team 3-D printed lines as narrow as 20 micrometers. That’s about half the width of a really fine human hair! The scientists shared their achievement November 21 in Science Advances.

Daniel Preston is an engineer at Rice University in Houston, Texas, who did not take part in the work. Nozzle tips used in really fine-line 3-D printing can be expensive and hard to build, he notes. Borrowing parts from nature can help lower the cost, he says. And that, in turn, may make it accessible to more people.

Teeny tiny printing

Cao’s team looked at many animal parts that might work as printer nozzles. These included stingers, fangs and harpoons. But the team eventually zeroed in on the proboscis of the female Aedes aegypti mosquito. This organ is fairly straight, with an inner diameter between 10 and 20 micrometers. And it can withstand the pressure of ink being pushed through it.

At first, the plan was to use the proboscis as the nozzle for an existing 3-D printer. But pushing ink through the narrow tip might need more pressure than those printers could handle, says Cao. So his group designed a printer around the mosquito’s mouthpart. They coated the proboscis with resin to make it extra stable.

The device printed a honeycomb shape, the outline of a maple leaf and a structure to hold cell samples. All were created with existing bioink. This is a special ink used to 3-D print biological structures.

“This biological, nature-derived sample is much better than engineered material,” says team member Jianyu Li. He’s an engineer who specializes in biological materials at McGill. The best 3-D printing tips on the market have inner diameters of 35 to 40 micrometers. The mosquito proboscis nozzle is half that wide.

“I’m looking forward to seeing other biotic materials [added] in the 3-D printing process,” Preston says. Moving in that direction could “enable new capabilities,” he says. And, he adds, it could make microscopic engineering more sustainable.

Li would like to use the mosquito proboscis in biomedicine. For example, his lab wants to develop ways to use the proboscis as a tiny needle to deliver drugs.