These gems make their own way

Gemstones made in the lab could improve your cell phone or catch nasty bacteria in your water.

Share this:

- Share via email (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share to Google Classroom (Opens in new window) Google Classroom

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

By Roberta Kwok

We’re sitting on the seventh floor of a building in downtown San Francisco, upstairs from the famous jewelry store Tiffany & Co. But Chatham didn’t buy these gems at a jewelry store. His company, Chatham Created Gems & Diamonds, made them in its laboratories.

Usually, gemstones form below Earth’s surface. They can stay buried for many millions of years. But Chatham and other scientists are creating gemstones on their own. They do this by mimicking the processes that occur underground or by coming up with entirely new processes. Lab-made gems have the same appearance and basic chemical structures as the natural ones, and they can be produced in months or even days.

Because these gems are created in the laboratory, researchers can control the gems’ formation very carefully. Some lab-grown gems are even purer or tougher than natural gemstones. And the gems are good for more than just jewelry. They can be used to make tools, such as lasers and drills. Lab-made diamonds could even help scientists improve electronic devices or detect dangerous bacteria in drinking water.

An accidental emerald

But making gemstones isn’t easy.

Chatham’s father, Carroll Chatham, became interested in the problem when he was only a teenager. Carroll had read about a scientist who tried to create diamonds, and he wanted to try making diamonds too.

“Almost blew up his father’s house,” says Tom Chatham. The explosion was so strong that it also smashed all the windows in the house across the street.

Carroll didn’t give up. He decided to try making emerald instead. For a long time, he couldn’t get it to work. Then one day, he left an experiment running and went away to college. While he was gone, Carroll’s father shut off the power in the basement and cooled down the furnace holding Carroll’s mixture of chemicals. That turned out to be the missing step. When Carroll came back, an emerald had grown.

Cooking up a crystal

Most gemstones are hard pieces of mineral. In nature, some minerals form underground when hot liquid rock — magma — cools down. Some of the atoms and molecules in the liquid start attaching to each other in repeating patterns, creating a structure called a crystal. If the mineral is beautiful, durable and rare, it is often considered a gemstone. Gemstones also form when minerals are heated up, squeezed, or exposed to new chemical elements.

When volcanoes erupt or mountains form, the gemstones get pushed closer to the surface. Or, over time, the rocks above wear away, uncovering the gems underneath.

To make a gemstone in the lab, researchers can imitate the Earth’s process. Each gem has a “recipe” with certain chemical ingredients. For example, emerald can be made with aluminum oxide, beryllium, silica, and bits of chromium. Rubies contain aluminum oxide and a little chromium.

Scientists usually melt the ingredients or dissolve them in water or other chemicals. The mixture can get as hot as 1,000 degrees Celsius — 10 times hotter than the temperature needed to boil water. Then the liquid is slowly cooled down. The cooling takes energy away from the atoms and molecules in the mixture, and they start to come together into a crystal. The crystal actually “grows,” as if bricks were arranging themselves into a house.

Because they contain the same ingredients, lab-made and natural gems can be hard to tell apart. But there are tiny differences. For example, many natural gems contain very small amounts of water, but some lab-grown gems do not, says James Shigley, a geologist at the Gemological Institute of America in Carlsbad, Calif. And certain lab-made gems may have bits of platinum that wouldn’t be found in natural gems.

While gemstones are forming, they can get traces of other materials stuck inside them, called inclusions. Lab-made gems often contain fewer inclusions than natural gems because scientists can control the growth conditions. “Natural gems just represent a fortunate accident in the Earth,” says Shigley.

Big crush

Diamonds are a little different from other gemstones because it takes huge amounts of pressure for diamonds to form. Imagine if the Eiffel Tower was pointed upside down and resting on its tip. Now imagine all that weight is pressing down on a point a few centimeters wide. That’s how much pressure a natural diamond feels deep inside the Earth, says George Harlow, a mineralogist at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City.

When the graphite dissolves, it separates into individual carbon atoms. The carbon atoms start attaching to the seed, making it grow. “Four days later, out comes a diamond,” says Karl Pearson, the senior vice president of technology and engineering at Gemesis. A company called Gemesis in Sarasota, Fla., has hundreds of diamond-making machines. The scientists start with a tiny “seed,” a piece of diamond about the size of a period at the end of a sentence. They put the seed into a ceramic container with graphite and a secret mixture of other chemicals. Finally, they close the container, squeeze it with blocks of metal, and heat it up.

Microwaving a diamond

Other researchers are making diamonds using a method that is completely different from Earth’s. The process is called chemical vapor deposition, or CVD. With CVD, scientists can make bigger pieces of diamond faster. They can also make thin diamond layers that could be used in high-tech devices.

“Then we microwave it,” says Joe Lai, a materials scientist at the lab. The microwave is similar to the microwave you would use at home to heat up your food, only more powerful. The hydrogen and carbon atoms break apart and then form into one very bright, very hot ball of gas. Carbon atoms bond to the diamond seed, making it bigger and bigger.

The Carnegie researchers have improved the CVD process so that diamonds grow more quickly. In 2002, they showed that their CVD process could grow single diamond crystals about 100 times faster than the microwave method had before. And the team can make their diamonds tougher than natural diamonds by adding a chemical element called boron. The boron keeps cracks from spreading, so it’s harder to break the diamond apart.

Tattoos, teeth and cell phones

Lab-made gems can be used for more than just rings and necklaces. For example, some supermarkets use sapphire in the check-out scanners. When a cashier needs to find out the price of a product — say, a box of cookies — a laser beam shines through a sapphire plate to scan a code on the box. Without a hard material like sapphire, the plate would quickly get scratched, and the scanner wouldn’t work as well.

Rubies are special because they can create laser beams. If you place a ruby rod between two mirrors and flash a very intense light at it, the ruby will shoot out a beam of red light. Ruby lasers can help remove tattoos because the red light breaks down certain colors of tattoo dye in a person’s skin.

But perhaps the most amazing gem of all is diamond. Diamond is so hard that it is used to cut rock and drill for oil. If you have ever had a cavity filled at the dentist, a diamond-tipped drill may have been used to remove part of your tooth.

Diamond lets heat pass right through it, so a diamond stays cool. “I could take a blowtorch, heat up a diamond till it’s glowing hot, put it on a metal surface and pick it up a couple seconds later, and it won’t be hot at all,” says Lai. Instead of holding the heat, the diamond transfers the heat to the metal. And diamond is very stiff, meaning that it is hard to bend.

“It really is nature’s extreme material,” says John Carlisle, a physicist and chief technical officer at the company Advanced Diamond Technologies Inc. in Romeoville, Ill.

Some of these properties could make diamond useful in cell phones. With today’s cell phones, people can talk to friends, surf the Internet and download videos. When you do these things, the phone uses parts called acoustic filters. Currently, these filters can be made of materials such as quartz or ceramic. Each filter must vibrate at a certain rate in order for the phone to work. Some filters have to vibrate more than a billion times per second.

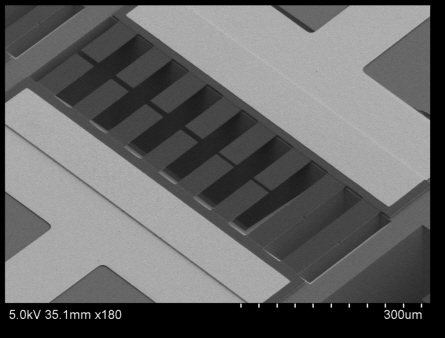

Because diamond is so stiff, it can vibrate at a very fast rate. Researchers are now working on creating tiny diamond filters, smaller than the width of a strand of hair. These filters could make the cell phone use less power, so the battery would last longer.

Diving boards for bacteria

Lab-made diamond could even be used to help find bacteria in the water that we drink. Bacteria are small organisms that you can’t see. Some of them can make you very sick.

People could put these sensors in water treatment plants or on sinks in their homes. If bacteria got stuck to them, the diving boards would vibrate a little more slowly than usual. That would send an electrical signal to tell people that the water may be dangerous to drink.

If the diving boards were made of other materials, such as silicon or gold, the molecules that catch the bacteria would fall off after awhile. But with diamond, the molecules stay attached. So researchers can leave the sensors in the water for a long time.

Lab-made diamonds could be better for high-tech devices than natural diamonds because it’s easier to get large amounts of diamond in the right shape and size. These diamonds could also be used in devices that help blind people see, in radar equipment for the military, and in advanced computers for sending secret information that can’t be decoded. “There’s just 101 uses for it,” says Carlisle.